Exactly 20 years after the accident that left BU hockey player Travis Roy paralyzed from the neck down, he was celebrated by the city of Boston and by his alma mater. Roy appeared on ESPN, the Boston Bruins signed him to a one-day contract, and Mayor Marty Walsh declared October 20 “Travis Roy Day” in Boston.

That night, at a gala at Agganis Arena benefiting the foundation that bears his name, Roy (COM’00) also celebrated that his foundation had raised more than $6 million over the years—$1 million that night alone—to help those with spinal cord injuries lead independent lives by providing accessibility through wheelchairs, computers, and vehicle lifts. The Travis Roy Foundation also funds research with the hope that it will lead to a cure.

Early in the evening, Christopher Moore, dean of Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences, came to the stage to announce a surprise: a $2.5 million gift from a group of anonymous donors that will establish the Travis M. Roy Professorship in Rehabilitation Sciences at Sargent and provide the foundation with office space on campus and a $50,000 annual stipend toward staffing for the next 10 years.

“The 11 seconds at Walter Brown Arena playing for Boston University were the best 11 seconds of my life.”

On stage, dressed in khakis, a Terrier-red tie, and a suit coat, Roy reflected on his life.

“Twenty years ago tonight, I lived out my dream of playing Division I hockey,” said Roy, who had been recruited to play on BU’s defending national championship team in 1995. “The 11 seconds at Walter Brown Arena playing for Boston University were the best 11 seconds of my life.” In the 12th second, the freshman forward crashed headlong into the boards, shattering his fourth and fifth cervical vertebrae, severely damaging his spinal cord, and leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. Roy acknowledged that lying in the intensive care unit for two months, supported by a ventilator, he wondered if his life was worth living. He had no idea what being paralyzed meant and assumed he would live as a burden with his parents. But today, he said, his life has value.

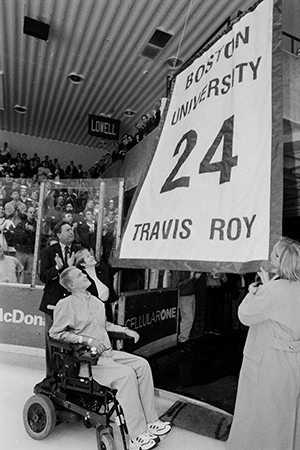

Leading up to the anniversary of his accident, Roy was interviewed many times by local and national media. Photo by Cydney Scott

“Once I decided I did want to live, I realized I could live according to the same values that made me successful before my accident,” he said. “My work on the Travis Roy Foundation alongside my friends and family has helped me create a life that is very rich, very much worth living….I feel so loved. I realize that my work is my new dream, and that’s what fuels me.”

Roy’s parents, former teammate Dan Ronan (COM’99, LAW’05), ESPN anchor John Buccigross, and friend and former hockey coach Jack Parker (Questrom’68, Hon.’97) were in the crowd. The longtime BU head coach said that while Roy’s injury was the worst thing to happen during his coaching career, the community’s support following the injury was the best.

In the years since Roy’s accident, donations have come from across the country. Roy remembers the little boy who broke open his piggy bank to send him $7.23 and the couple who opted not to go on their honeymoon, and instead gave the $5,000 to him. His BU classmates manned phones during a telethon benefit drive. Without those donations, Roy says, he wouldn’t be leading the life he has now, one full of challenges, but also independence and fulfillment.

“My work on the Travis Roy Foundation alongside my friends and family has helped me create a life that is very rich, very much worth living… I feel so loved.”

That initial support, coupled with insurance BU bought through the NCAA, provides Roy with 24-hour care in his sun-drenched apartment on Comm Ave, not far from Kenmore Square. “When you have 24-hour home care, you can do things when you want to do them,” he says. “When I want to get up, there’s someone there to get me up, and showered, shaved, dressed—it takes a couple of hours. If I need to go to a speaking engagement or a meeting, they’re there to take me. When I want to eat, I can eat.”

Not everyone is so fortunate. Roy says many paraplegics are afforded only a limited amount of home care, dictating how often they can leave the house. It puts a strain on family and friends, who are forced to become caregivers.

Roy hears these stories during his 50-hour workweek with the Travis Roy Foundation, now in its 18th year. When it started, it was able to give out 5 or 6 grants a year; today, it gives 150 grants a year, making home modifications so a 17-year-old boy, paralyzed in a car accident, can return home, and installing a lift so a father who fell off a ladder can reach the second floor of his home to tuck his children into bed.

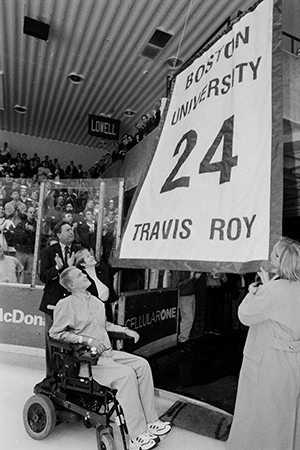

Travis Roy’s hockey jersey number, 24, is retired and hoisted to the rafters of Walter Brown Arena in 1999. Photo by Albert L’Etoile

Other foundation work has Roy visiting survivors of spinal cord injuries and their families in the hospital. “When I go in, I don’t preach,” he says. “I know life will get better than they realize, and it takes time. I think the best thing I can do is roll in there and present myself, look good, and talk about what I’m doing. They need to see that things will get better.”

When Roy started his foundation, he imagined a breakthrough would arrive within 10 years (he still hopes to go out of business one day). So far, the foundation has given $2.1 million to cutting-edge research. In conjunction with the Christopher Reeve Foundation (which gave Roy the Christopher Reeve Spirit of Courage Award in January 2015), the Travis Roy Foundation is funding one of the first clinical trials involving the implanting of a device on the spine of people with paralysis that stimulates the nerves and reminds them how to work again. The Travis Roy Foundation is also funding research at Stanford University and Burke Medical Research Institute.

Roy’s income comes from speaking engagements around the country. In the hours before his gala at Agganis, he greeted a group of local children with fist-bumps, slightly lifting his right hand off of the arm of his wheelchair and usually getting a smile in return. Now 40, he connected to the kids by sharing what it was like to grow up a rink rat in Maine, on skates before he turned two.

He urged them to set goals, just as he had done as a high school freshman, writing down his hopes of making the varsity team, a Division I hockey team, the NHL, and maybe the US Olympic team. When he showed his parents those goals, his father reminded him that first he would need the grades to play in college, handing him another challenge—getting good grades—since he had a mild form of dyslexia.

“Sometimes, we choose our challenges and dreams, and if we’re really lucky, we can reach them,” Roy said. “But there are other times in life when the challenges simply choose us, and it’s what we do in the face of the challenges that defines who we are. More often than not, the challenges choose you. But from sports and my teachers, I learned to never give up, no matter how bad things went. You always have to have the desire to get back up.”

I love reading articles about Travis. They are always very upbeat, positive, and make you feel good that someone despite what he’s gone through is living life to the fullest each day.