Robert Hausman knew how to get his students’ attention. During lectures on cell biology, he often climbed onto desks and chairs. He carried a measuring stick, which he occasionally slapped on desks to emphasize a point. “Rob was such a vivacious lecturer,” says Dean Tolan, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of biology, who had worked with Hausman. “I was always fascinated by his teaching style.”

Hausman, a CAS professor of biology, so loved teaching that he was determined to return to the classroom after a devastating injury in October 2010. He fell off a ladder at his home, an accident that left him a quadriplegic. He underwent rehabilitation and by spring 2012 he was teaching immunology at BU. It was his last course. “He came back with the same sort of wry sense of humor and quick wit, like okay, this is just the new normal now,” Tolan says.

Hausman, who also was the biology department’s director of graduate studies, died on April 25, 2015. He was 68.

“He was an inspiration to us all,” says Tolan. “We really miss his commitment. We really miss him.”

Hausman earned a dual BA-MA in biology at Case Western Reserve University and a PhD in biological science at Northwestern University. In 1978, after completing postdoctoral research at the University of Chicago, he joined BU’s biology department as an assistant professor.

He was the cornerstone of the undergraduate cell and molecular biology curricula, teaching the second-semester cell biology lecture class, as well as an honors cell biology course and a graduate seminar on biochemical and molecular aspects of development. Hausman coauthored the textbook The Cell: A Molecular Approach with Geoffrey Cooper, a CAS professor of biology and associate dean of the natural sciences faculty.

In 1987, Hausman became the department’s director of graduate studies, a position that suited him, Tolan says. “It’s not an easy job, but Rob was great at what it entailed, dealing with faculty members and their students. He knew when to intervene and when not to intervene. He was an artist at it.”

He also was a respected mentor. “Rob had this magnificent, soothing, Brahmin accent—I still remember the first time I heard it,” Tolan says. “He was one of the reasons I came to BU. He helped me see research projects that wouldn’t have been visible otherwise.”

Hausman left a lasting impression on many of his students as well. “Rob was not only a memorable mentor,” says Bukhtiar Shah (GRS’93), who worked with him while pursuing a PhD, “but also a very fine human being.” Hausman, he says, treated his students “like family. He was always prepared to listen to and solve our problems.”

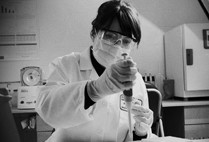

He was equally dedicated to his own research, says Bill Eldred, a CAS professor of biology. Hausman specialized in nervous system development, focusing on the retinal and muscle development in chick embryos. He discovered and purified a protein in chick retinas he called cognin, which enables retinal neurons to recognize each other and group together, playing an important role in the overall development of the retina.

According to both Eldred and Tolan, Hausman’s passion for his research played a key role in his ability to develop a strong neurobiology curriculum at the University. “Before Rob arrived,” Eldred says, “there were practically no neuroscience courses at BU.” Hausman, says Tolan, “has left a great legacy.”

I worked for Dr. Hausman when I was in undergrad. I got my first exposure to cell culture, tissue dissection and other cell biology techniques which Ultimately my love for medicine and science. Dr. Hausman was instrumental in directing my efforts towards a career in medicine