Art in ’08: A Close Encounter with Genius

Painter Chuck Close and curator Robert Storr in conversation

At BU, the visual arts mean more than pictures hanging in galleries. Art means images from a cross-country trip painted on walls, delicate sculptures made of concrete and steel, and innovative ways of looking at the world. This week, BU Today looks back at the year in visual arts at Boston University. Click here to watch Chuck Close on BUniverse.

Every artist needs a spokesman — someone who understands and values his or her work and helps to share its meaning with the rest of the world. For world-renowned painter and printmaker Chuck Close, that person is distinguished curator and arts writer Robert Storr, a longtime friend. Storr cowrote the first book on Close’s work, has written countless essays on Close, and has curated many exhibitions of his work; on a personal level, Storr helped the artist define his style after a 1988 illness that left him paralyzed. When the two speak, Close says, “I’ll say things that I don’t normally say and think about stuff in a different way.”

Storr and Close will demonstrate that creative give-and-take in Chuck Close and Robert Storr in Conversation, the fourth in the annual Tim Hamill Visiting Artist Lecture Series, tonight, November 1, at 6 p.m. in Morse Auditorium. The series, named for painter and printmaker Hamill (CFA’65,’68), director of Boston’s Hamill Gallery of African Art, presents artists whose work crosses boundaries among artistic disciplines.

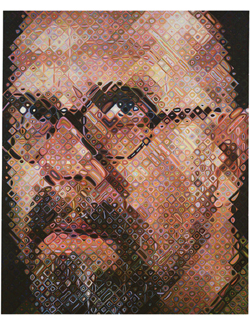

Throughout the past four decades, Close has experimented with a range of media, among them paint (usually acrylic, with an airbrush, a paintbrush, and even his fingers) and printmaking (using woodblock, reduction block, and scribbling/etching techniques). He works from a gridded photograph — a mug shot–style Polaroid — to create large-scale, psychologically charged portraits of family, friends, and fellow artists.

His subjects stare down at the viewer; their faces, with every blemish, freckle, and wrinkle visible, fill the canvas. “I love the fact that a person’s face is almost a road map of their lives,” Close says. “And embedded in it are all kinds of indications of what kind of lives they’ve led. If they’ve laughed their whole lives, they have laugh lines, and if they’ve cried their whole lives, they have furrows in their brow.”

Although he aims to depict people with great detail and “without editorial comment,” Close challenges the photorealist label often given to his style. He strives to create a realistic rendering, but he also is aware of its artificiality: the viewer “sees” a person, he says, but in truth, what he or she sees is only paint on a canvas.

Close explores this tension between flat surface and artificial depth further in portraits that use abstract cells, begun in the 1970s. Up close, a multitude of miniature abstract paintings are visible. From afar, the cells cohere to form a distinct face. “It rips back and forth from the marks on the surface, which say flat, flat, flat, and warps into an image,” he says. “Just as you’re comfortable looking at it as an image, it flattens back out again. I love the fact that it makes space where there is no space. It reminds you of life experiences you’ve had, and it’s just colored dirt.”

Close’s paintings not only rely on his subjects and his own passion for the medium, but on display as well. “In a way, what a curator does is like a travel agent,” Close says. “He sort of takes you on a guided tour of someone’s career.” And what makes Storr such a successful guide, at least in Close’s mind? He, too, is a painter. “Once you push paint around, you look at painting differently as an activity,” Close says. “He’s been extremely clear about certain issues of my work from the point of view of someone who has shared experience.”

Storr is the dean of the Yale School of Art and a consulting curator of modern and contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This year, he became the first American to serve as artistic director for the Venice Biennale, and he has curated numerous exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and elsewhere.

Storr curated Close’s MoMA retrospective in 1998, 10 years after the artist’s life-changing illness. A blood clot had formed in Close’s spine, leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. As soon as he could hold a brush in his mouth, and then after some rehabilitation, tape one to his hand, he continued to paint. The MoMA retrospective demonstrated the continuity of Close’s work following his illness.

“Storr has some of the most cogent and essential things to say about my work,” Close says. “We always enjoy talking to each other, so tonight we’ll just do what we always do, only there will be other people there.”

Chuck Close and Robert Storr in Conversation, the fourth in the annual Tim Hamill Visiting Artist Lecture Series, is tonight, November 1, at 6 p.m. in Morse Auditorium, 602 Commonwealth Ave. The event, hosted by the College of Fine Arts school of visual arts, is free and open to the public.

Rebecca McNamara can be reached at ramc@bu.edu.

This article originally ran November 1, 2007.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.