BU Rocks: A Cosmic Mystery, with Music

Prof finds origins of black-hole plasma beams, and sings about it

BU and rock ‘n rollare in a long-term relationship — just ask the members of Aerosmith,who got their start playing parties in the dorms. Kenmore Square andthe BU campus have changed since then, but the University’s musicaltradition hasn’t gone away. This week, we highlight five BU bands towatch for.

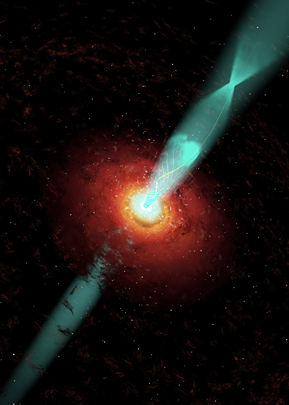

It’s a paradox of galactic proportions: from the midst of black holes, born of collapsed stars and known for their intense matter- and light-trapping gravity, astronomers have long detected massive jets of hot, ionized gas — known as blazars — shooting out at nearly the speed of light.

“It’s the last place you’d expect that,” says Alan Marscher, a College of Arts and Sciences professor of astronomy, who has puzzled over this phenomenon for more than a quarter century. Marscher even wrote a song about this obsession — it’s called “Superluminal Lover” (click the player below to hear), and he’s performed it in classes and at astronomy conventions around the country.

Now, the mystery of blazar origins may be solved, thanks to observations made by Marscher and other astronomers in his lab using a combination of telescopes trained on a plasma jet shooting out from one particular black hole. Their findings, published in the journal Nature in April 2008, reveal that the plasma jets are propelled by energy released from tightly coiled magnetic fields surrounding the black hole. The results are the first observational evidence supporting the theoretical computer models of blazar birth.

The black hole Marscher and his team focused on sits about 950 million light years away (a light year is the distance light travels in a year, about 6 trillion miles). It’s big, very big — 200 million times more massive than the sun. Gamma rays and X-rays shoot out with its jet of charged particles, aiming almost directly at Earth, Marscher says, “like a halogen flashlight.”

Marscher and his team began by peering at the plasma jet using 10 radio telescopes scattered around the United States, including one located on the property of BU’s Sargent Center for Outdoor Education in Hancock, N.H. The resulting images were extremely detailed, but only to within about a light year out from the black hole.

“We wanted to get closer than that,” says Marscher. In recent years, they added X-ray measurments from NASA’s orbiting Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer and observations from optical telescopes, stationed in the United States and Russia, which they used to measure changes in brightness and the polarization of the visible light.

“That turned out to be the extra piece that was needed,” he says. During a 10-day period in late October and early November 2005, they watched the blazar every night, and this concentrated observation allowed them to see the rotation of the polarization, a quality of light associated with magnetic fields. At the same time, they observed “big explosive outbursts of light at all wavelengths and a shower of particles of very high energy coming from the same region.”

Taken together, the evidence supported a theory of blazar birth that had previously played out only in computational models: that the matter entering a black hole forms a rotating disc, and at the poles of this disc, twisted, coiled magnetic fields wind up like a corkscrew and blast matter and light back out into space. Indeed, the reasons for the blazars’ existence, Marscher says, is probably to release the magnetic tension built up by so much matter falling into the black hole.

The next step, he says, is to see if other blazars, which are also found emanating from newly formed stars, behave the same way. That phase of the research begins Thursday, June 5, with the scheduled launch of NASA’s Gamma-ray Large Area Space Telescope (GLAST). This sensitive, wide field-of-view space observatory will scan the entire sky every three hours, collecting data on mysterious gamma-ray sources.

“It will give us the kind of concentrated data we need,” says Marscher. “Blazars are like children. They have basic similarities, but each has their own personality.”

Under the stage name Cosmos II, Alan Marscher, a CAS professor of astronomy, is a well-known troubadour of cosmic phenomena. He’s written and performed about a dozen songs to entertain and enlighten his students. Click here to listen to Marscher’s homage to black holes and blazars, “Superluminal Lover.”

Chris Berdik can be reached at cberdik@bu.edu.

This story originally ran June 4, 2008.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.