Are Safer Cigarettes a Corporate Ploy, and FDA Mistake?

Bicknell Lecture tomorrow delves into tobacco regulation

Antismoking advocates recently pushed through legislation that gives the Food and Drug Administration broad new powers to regulate tobacco. The legislation requires that health warnings on tobacco products be larger, bans candy and fruit-flavored cigarettes, and sets other sales restrictions, seen by some as major steps in the campaign to reduce smoking.

But it also puts the federal government in the most unusual position of endorsing products known to cause thousands of deaths each year.

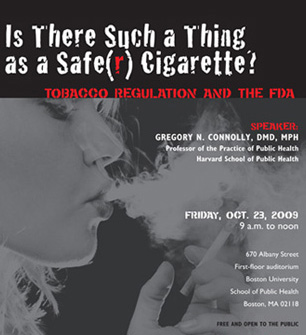

Public health advocates say the legislation offers powerful lessons about political compromise, the role of the federal government in protecting public health, and the power of industry. This year’s William J. Bicknell Lectureship in Public Health, being held tomorrow, October 23, at the BU School of Public Health, will take a deep draw on these issues.

Gregory Connolly, a professor of the practice of public health at the Harvard School of Public Health, will speak on the topic Is There Such a Thing as a Safe(r) Cigarette? Tobacco and FDA Regulation.

A panel discussion with Patrick Basham of the Democracy Institute, Cheryl Healton of the American Legacy Foundation, and Michael Siegel, a professor in the department of community health sciences at the BU School of Public Health, will follow Connolly’s talk. The event is free and open to the public and includes an audience question-and-answer session.

Siegel, an expert on tobacco control, frames some issues surrounding the FDA’s new powers to regulate tobacco in anticipation of the lecture.

BU Today: This new legislation gives the FDA authority to regulate cigarettes, a step advocates say will make them safer. What’s your view?

Siegel: The issue we need to think about is whether or not there is even such a thing as a safer cigarette. The mandate the FDA has been given is to develop one. Is that even possible? What would a safer cigarette look like? How is the FDA supposed to develop one? There’s no guidance in the law, except to say that they can lower the level of certain constituents, such as nicotine and other chemicals. But even if it’s possible to create a cigarette that somehow lowers the risk, would it be beneficial to public health?

Won’t smoking be safer if the FDA limits toxins in tobacco products?

If the FDA issues a mandate that cigarettes are safer, more adults may start smoking or more youth may start. Cigarette companies did the same thing for many years: Marlboro Lights and Camel Lights were an attempt to market a safer cigarette. But these are not safer. Because they’ve lowered the delivery of nicotine and other substances, people inhale more deeply and smoke more. What these products also have done is inhibit people from quitting because people who otherwise might have quit now think, I’m switching to a safer cigarette, so I don’t have to quit.

So is it really in the public health interest to mandate a safer cigarette, when that may undermine the public’s appreciation of the hazards of smoking? Is the way to intervene on this issue to take out some of the toxins, or do you put your efforts into trying to get people not to smoke?

You’ve criticized the FDA for coming down hard on e-cigarettes, battery-powered devices that provide tobaccoless doses of nicotine in a vaporized solution. Some argue that e-cigarettes appear to be a relatively safe and effective quit-smoking device — what do you make of the FDA warnings about their possible harmful ingredients?

The presence of e-cigarettes essentially nullifies the entire FDA search for a safer cigarette. Since we now have a nontobacco product available that is acceptable to smokers as a substitute, it makes any reduced risk tobacco product inappropriate. If you know you have a product that doesn’t deliver tobacco, just nicotine, why would the federal government tell the public to use a product that does contain tobacco? Isn’t there a contradiction here if the FDA bans electronic cigarettes, but sanctions tobacco cigarettes?

Why should people who don’t care about smoking care about this?

The issue is much bigger than smoking. The fact that the federal government is now in the business of approving or disapproving cigarettes for sale means it is involved in the sale and marketing of a deadly product. Doesn’t this undermine the system of public health, when you have an agency whose mission is to make sure that our food and drug supply is safe approving deadly products? Doesn’t this make the federal government complicit in the tobacco epidemic?

It seems antismoking groups had to make some concessions to Big Tobacco to win gains in warning labels and advertising restrictions. Isn’t that the nature of political compromise?

I look at the legislation and see a bill that absolutely protects the tobacco companies’ interests — specifically Philip Morris. It gives the FDA a mandate, setting up impossible standards for new products to enter the market. It ensures that existing products will be institutionalized and protected from competition.

It raises the questions: what is the role of political compromise, and what is real compromise if you have to have the support of your opponent on every point? These questions are applicable to other issues, such as the health-care legislation Congress is debating. If the only way you can get health care through is to bring insurance companies on board, is the result really worth it?

Those are some of the issues we’ll be discussing.

The William J. Bicknell Lectureship in Public Health was established at SPH in 1999 to bring lectures by stimulating iconoclasts and original thinkers to the school, stretching the minds of students and faculty. The lectureship is endowed by a gift from William J. Bicknell, founding chairman of the SPH department of international health and a professor of international health. The lecture is tomorrow, Friday, October 23, from 9 a.m. to noon, in the first floor auditorium of 670 Albany St., on the BU Medical Campus. A continental breakfast will be available at 8:30 a.m. The event is free and open to the public.

Seth Rolbein can be reached at srolbein@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.