Chicago Comes to Agganis

Robert Lamm muses on the band’s four successful decades, and a BU connection

The jazz-rock fusion band Chicago is one of the most durable, successful American bands of all time — consider their stats: since forming in 1967, Chicago has sold more than 120 million records and has had 19 gold, 13 platinum, and 12 top-10 albums (5 reaching number one). Only the Beach Boys have released more singles and albums.

The band kicked off its latest tour last week, the third with another stalwart, Earth, Wind & Fire. The tour adds a humanitarian dimension: fans who bring three cans of food (or $3) to benefit the nonprofit grassroots organization World Hunger Year get to download three new collaborative songs by the two bands.

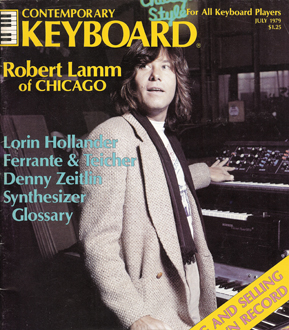

The bands reach Boston University’s Agganis Arena tomorrow night, a special stop along the way for Robert Lamm, the band’s keyboardist, vocalist, a founding member, and driving force: his daughter Sean (COM’11) attends BU.

Lamm composed many of the band’s biggest hits, including “Beginnings,” “Saturday in the Park,” “25 or 6 to 4,” and “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” BU Today found him for a phone interview from Charlotte, N.C., as the tour was working its way north.

BU Today: How’s this newest tour going?

BU Today: How’s this newest tour going?

Lamm: We just started a couple of days ago, but so far the crowds have been amazing. People love the songs.

Does it get exhausting?

We’ve been touring every year since we’ve been together. In the beginning, we were playing about 300 shows a year. Now we play about 150. We basically get to play and write what we want, though. The traveling got harder after 9/11, but I think we’ve all adapted; it’s become comfortable for us. I love traveling — my wife and I travel a lot when we’re not on tour.

What are your favorite moments from touring over the years?

No matter where in the world we’re playing, for 10,000 people sometimes, they’re singing the words in English. Last year we toured Europe, and we hadn’t been there for a while. We didn’t know if they’d remember us, but we came out smokin’, and they were totally with us.

I’ll always remember when we pulled up to our hotel in Paris, I grabbed trumpet player Lee Loughnane and said, “Hey man, do you remember the first time we came to Paris?” When he said, “Yeah,” I said, “Look across the street: that’s the hotel we stayed in.” It wasn’t déjà vu — it was coming full circle.

Playing in Carnegie Hall with my mom in the audience, that was a moment. I have a million of them. I’ve been able to take each one of my daughters on tour with me since they were small, one at a time, so they could visualize what it was like. One of my daughters actually goes to BU.

How does she like it?

She loves it. She’s leaning towards journalism, both writing and electronic.

A girl after my own heart. What are your memories of Boston?

One of our first times in Boston, we played on the bill with this Boston group J. Geils, and then the next day we played a free concert on the Cambridge Common with Alice Cooper. Those were the days when everyone was playing for free.

Another time we played at this venue called the Boston Tea Party; it was basically a big empty church. We asked a promoter if we could rehearse there before the show, so he gave us the keys. We were still very young, only been together a few years; we jammed all night, changing instruments. It was really a uniting experience, a bonding thing on a musical level that has stood the test of time; I mean, out of the original six guys, four of us are still around.

How have you managed to stay together for so long?

Most of us were music majors at various schools around Chicago. Our focus was music and our mission was music, so that was always the plan. It wasn’t about being famous or getting girls or any of the other reasons people put bands together. It was a very ’60s-’70s work ethic, more like a community — there were enough guys in the band that we could actually call it a community.

That’s really how we stay together, because we’re always thinking about the next thing, what the next project might be about. That keeps us on the same page. When we’re not working we go our different ways. We all have families; we don’t even all live in the same town anymore.

Your style has been infused with different genres. How did you come up with that sound?

When we first got together in the basement of saxophonist Walter Parazaider’s parents’ house in Chicago, we just started to play, and the sound you hear on the records is the way we sounded then. It was so freaky: three horn players, me on organ and electric piano, a drummer, and a guitarist, and that’s pretty much what we sounded like. The nature of the sound, the combination of instruments, and the influences — that was a happy accident.

What does “25 or 6 to 4” actually mean?

It’s a reference to time. It’s a song about writing the song, and I looked at my watch while I was writing and it was 25 minutes to four in the morning, or maybe 26. Some of the guys in Earth, Wind & Fire say to me, “I know you were doing acid when you wrote that song!” Of course I said, “No, no, you’ve got it wrong.” Though it was the acid era.

What was your audience like in those earlier days?

If you’ve seen the movie Woodstock, our audiences looked like that. The thing about music audiences, even today, and I don’t care where you are, what country you’re in, is that they look and react the same. Because it’s music, and music is communicating, emotionally and viscerally, so people seem to have the same look on their faces, whether it be amazement or disgust.

It must be fascinating to see your audience change over the years and still have that same reaction.

This guy once said that every 100 years everyone on the planet is gone and there’s a whole bunch of new people. In a small way, that’s what our shows are like. It’s the same people — they look the same — and generally they’re anywhere from 20 to 40, with some older folks who like the horns that take them back to the big band era. That’s always been our audience; it’s always replenishing.

I’ve read that Thelonious Monk was a strong influence on you.

In the beginning, that’s who I could relate to as a piano player. I liked that he was anti-technique, but still found ways to make good music. As someone with not much technique myself, I loved that. But basically I’m a composer, a songwriter, so a lot of my influences range from Dylan to Lennon and McCartney to Antonio Carlos Jobim to Burt Bacharach to Marvin Gaye, Neil Young — the list goes on.

Do you listen to new music?

I heard a new band called White Rabbits; they’re really good. I’m into electronica; there are DJs and remix artists who are really doing cool things; guys named Coop, Ray and Christian. I really like what M.I.A.’s been doing, especially with A. H. Ramen, the stuff from Slumdog Millionaire. Before she got so huge on TV, I liked Feist’s early stuff, too.

Do you think you’ll ever decide enough is enough?

I suppose if we really start to suck, we’ll quit, but I don’t see that happening anytime soon. People all over the world love Chicago’s music. We still look and feel good and have the edge, so there’s no reason to think about it at the moment.

Chicago, with Earth, Wind & Fire, plays tomorrow night, June 16, at 7:30 p.m. at Agganis Arena, 925 Commonwealth Ave. Purchase tickets here. And don’t forget your cans.

Devon Maloney can be reached at devon.maloney@gmail.com.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.