Drug Companies Target Teens Online

Predatory marketing explored at drug policy conference held at BU

Ann Woloson recounts a recent visit to a pharmacy to develop film, the first time she’d stepped foot in a Walgreen’s. At the register, Woloson was asked for her phone number. She gave her cell and was alarmed when the cashier found the data already stored in the computer system.

“I’d never bought anything at a Walgreen’s before,” she says. “Evidently, my cell phone company sold my number to Walgreen’s.”

If it’s that easy for an adult’s information to be unknowingly harvested and sold, Woloson says, what protection do young people have?

Woloson, executive director of Maine-based Prescription Policy Choices, a nonprofit educational and public policy organization that provides expertise on prescription drug policy, visited campus last week to discuss predatory marketing practices, in particular how pharmaceutical companies use the Internet to glean personal information from teenagers.

She spoke at the fall conference of the National Legislative Association on Prescription Drug Prices (NLARx), which was hosted by the BU School of Law. The conference detailed efforts to regulate drug marketing and discussed upcoming legislative agendas. NLARx is a bipartisan, independent, nonprofit organization founded by state legislators seeking to reduce drug prices and expand access to prescription medicines.

Woloson’s presentation described pop-up ads that lure kids to drug and medical device Web sites. The sites provide product information and offer gifts such as art supplies, backpacks, and music downloads, as well as coupons and free samples, in exchange for personal information. Teens are also targeted on Facebook, MySpace, and through text messages.

BU Today: How prevalent is this type of predatory marketing?

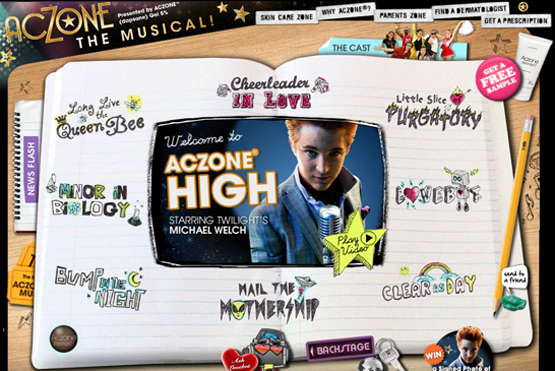

Woloson: Very. The use of technology has changed significantly over the last decade and regulators have not been able to keep up. I just came across a site for acne medication. It’s a High School Musical kind of thing. What’s most offensive is that in order to get the free coupon, you have to give your name, e-mail, and date of birth. Most sites have a box that says “check here” to receive more information. On this one, you can’t get to the next page unless you check that box.

I’m not spending time on Facebook myself, but when my daughter’s on, she’ll call me over. They have little pop-ups that lead you to these sites. I can’t speak to how many teenagers use them, but pharmaceutical industries are not the only ones investing more in online marketing; 10 percent of our overall growth in spending for advertising is going to be over the Internet.

What’s being marketed to kids?

The sites I’ve looked at very closely are growth hormones, acne medications, and birth control. It’s not so much the marketing that I have a problem with; it’s the information that’s collected and what’s done with that information. It’s frequently shared or sold to other marketers. It’s data mined with other information from a drug company where you might have supplied your address, and that compilation is sold to other marketers. There’s no one really preventing them from doing that, except for the federal law COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act), which restricts marketing to kids under the age of 13.

Won’t parents decide what medications their kids take?

Not always. This is where I’ve been a little conflicted. There are teen girls who may want to be able to access certain health-care services that they may not want their parents to know about. They may be seeking assistance for sexual abuse or information for someone who wants to become sexually active. The law does allow these teenage girls to access information about birth control. But I don’t know why a drug company needs to have their name, date of birth, and e-mail in order to provide that information.

What’s the worst-case scenario?

Identity theft — young kids with their credit ruined perhaps for the rest of their lives. That’s where my concern was, but then I started learning about other things that can happen — kids being steered toward drugs that are not safe or are less safe or more expensive than others. There’s a birth control device called NuvaRing that is very appealing to young girls — you only have to insert it into your body once a month — but it provides them with no safety against sexually transmitted diseases. Not all the information about the risks associated with drugs or devices are obvious. The first thing the NuvaRing site does list is some of the risks. But it doesn’t show some of the most dangerous consequences, including those related to girls who smoke, until you keep clicking into the site, and I don’t believe most kids would go that far with it.

Maine came up with legislation, passed unanimously last spring but subsequently challenged on First Amendment grounds, to counter these practices.

The committee that first reviewed the law was so concerned about some things brought up at the hearing that they made the final legislation stronger, but it may have created some First Amendment speech problems. So the law is going to be repealed, and they’re going to rewrite it.

What were the issues?

Universities and newspapers filed suit against Maine because of this law, claiming they would not be able to request information over the Internet for legitimate purposes like college recruitment or applications. Newspapers claimed they wouldn’t be able to print sports events or honor rolls. I can see where they’re coming from.

What advice do you have for parents when it comes to predatory marketers?

Parents should talk to their kids about the problems that can occur. Even as an adult, if you give your address to Travelocity or somebody like that, you assume your information is staying right there. It’s not. It’s being sold all the time. Most adults are offended by that. The Federal Trade Commission, the agency charged with trying to prevent identity theft, says that if you’re going to give out your information, make sure you know who you’re dealing with. I would argue that teenagers giving out information over the Internet to a drug company really don’t know who they’re dealing with.

Caleb Daniloff can be reached at cdanilof@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.