Iceland’s Cold, Hard Fall

CAS prof says it will take generations to repair financial, political damage

With the collapse of their government last week, Icelanders are hoping they’ve finally hit bottom. It’s been a fast, hard fall since last October, when the nation’s overextended banking system melted down. The tiny island country is now on track for the world’s sharpest economic contraction — perhaps more than 10 percent, according to some economists.

The once-proud people, with the fifth highest per capita income in the world just six months ago, have become the butt of jokes internationally, such as there being an opportunity on eBay to buy the country. The normally placid and stoic citizens have pelted the former prime minister, Geir Haarde, with eggs and thrown rocks through the windows of Parliament. The government has borrowed $10 billion from the International Monetary Fund and others just to stay afloat, and the country may need to join the European Union for stability and security.

A welfare state with precious few industries, and built on a service economy — banking — that no longer services, Iceland looks to be in for a generation or two of hurt.

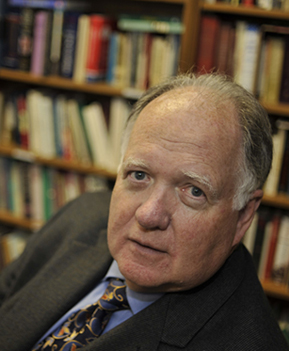

Michael Corgan, a College of Arts and Sciences associate professor of international relations, specializes in Icelandic affairs and teaches political science at the University of Iceland. BU Today asked Corgan how the government fell, what comes next for a population still reeling from profound financial calamity, and what role the United States played in all this.

BU Today: The global financial crisis has precipitated a hard fall for Iceland. Is this what brought the country’s government down?

Corgan: The government was seen as responsible for not providing sufficient regulation and not foreseeing what was coming. The central bank is also headed by David Oddsson, who had been prime minister for 13 years, so he was part of this government that didn’t do much to prevent the crisis. There were warning signals from Fitch and Moody’s months back that their banks were leveraged way beyond their capacity. Conservative estimates are that Iceland had banking liability about 10 times the GDP.

How does this economic and political catastrophe translate to the street. Are people losing their jobs?

People are losing jobs, yes. Iceland has a population of 306,000. The guest workers have gone home. And of working-age Icelanders, about 10,000 people will leave the country this year to seek jobs overseas and in Europe. The upshot is, the country will be paying off the $10 billion it has borrowed for the lifetimes of many people alive today.

With its service economy in shambles, how will the country pay off this debt?

Well, Iceland can’t catch more fish than it’s catching right now without depleting fish stocks. It had opened an aluminum smelting plant, which Alcoa took over to great opposition from around the world because they despoiled one of the last unspoiled areas in Europe. There’s been talk of shutting down the plant, but they probably won’t since Iceland is in such an economic catastrophe. They certainly won’t open another. So where else is there to get money? Iceland can pick up some money on tourism. It’ll help, but that’s all.

What does the collapse mean for Iceland’s political future?

The Left-Green Party and the Social Democratic Alliance got together and now have moved Iceland politics to the left. They had been on the right more or less for a long time, unlike the other four Nordic countries. By the way, the new prime minister, Johanna Sigurdardottir, is the first openly gay prime minister in Europe as far as I know.

Does Iceland have a history of public upheaval?

The recent throwing of rocks through Parliament was the third time there had been anything remotely resembling a riot in the country’s history. That hadn’t happened since Iceland joined NATO in 1949. Mind you, the riot police in Iceland use pepper spray and shove people around, but that’s about it. No violence. They’re Nordics after all.

You were there last November. What was the mood on the street?

Tense, but not impassioned. It’s not like what Greece had with the students being killed. What the people are most unhappy about is that the government has not confided in them. There’s an IMF plan, but you’d be hard put to find out what it is, and Geir Haarde, the former prime minister, kept saying they were going to follow the IMF plan. Well, what is that? The chief director of the central bank has ducked all responsibilities. Then there are the individuals who were the high flyers, the high rollers, multimillionaires, and a billionaire. They’ve almost disappeared from sight. I’m a little surprised that the Icelanders aren’t holding them more to account.

There’s been debate over whether Iceland will now join the European Union, and whether that’s a good thing or not.

If Iceland joins now, they join hat in hand and sacrifice some of their fishery stock to outside interests; that’s the only place they can really get money, so that will set them back further on the road to recovery. And being a country so small, they won’t account for much in EU voting.

What will they gain?

Currency stability. They would move to the euro. The public debt isn’t the problem. It’s the private debt of the three banks that the government has tried to nationalize. Joining the EU will give them some stability and some regularity, but they would still have some of these debts to pay off.

The United Kingdom used anti-terror laws to freeze Icelandic assets because so many Britons banked with Iceland. How are relations between the two today?

I don’t think Iceland is being described as a terrorist nation anymore. Icelanders have finally reassured the Brits that they’ll follow the rules for paying back at least individual subscribers. There’s no sense in beating up on Iceland — you can’t get any more. They’re trying to make amends and make the system right. A number of Brits are also saying that all of you who put money in banks with a high rate of return, you should have known that a high rate of return equals risk. Don’t pretend you had no idea that this could happen.

Why is this government collapse so important for the rest of the world?

It’s the canary in the coal mine for other countries in Europe: Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, maybe even Portugal. Look what happens when you have no regulation. They are the American system taken to the nth degree — low regulation, very speculative lending.

Is America responsible for any of this?

Iceland was the only banking system that didn’t buy any subprime stuff from America. But then people got nervous about banking systems generally and saw Iceland was overextended and started calling in loans. The credit system had frozen up, thanks to what we had done. The Icelanders don’t exactly blame us, because they know they put themselves out on a limb, but we made sure that the limb got sawed off. By bringing the whole economic system around the world down, suddenly, if you’re in trouble, there’s nowhere to go for a loan, no place for Iceland to get money. We can sell off parts of our land, we can sell off industries. We can mine more coal. We can do a lot of things. Iceland can’t. It’s producing what it can produce. The only other way it had of getting money was a service economy, and the sector they chose was banking and they screwed that up.

Caleb Daniloff can be reached at cdanilof@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.