Revisiting John Silber, the Old Nemesis

Feistiness, and candor, from the president the Freep loved to hate

In late 1970, Daily Free Press founder and first editor Charles Radin was closely following John Silber’s candidacy for University president. A vote by the Board of Trustees had been scheduled, but the Free Press had been barred from covering it, the location kept secret.

So Radin (COM’71) hatched a plan: he narrowed down possible locations and hid reporters in the closets.

“If my memory is correct, I think it was the LAW auditorium where they actually met,” Radin says. When the trustees announced near-unanimous approval for Silber’s appointment as BU’s seventh president, Radin put out an extra edition revealing that the vote included a number of abstentions and there had been several no-shows; almost half of the trustees were absent.

“Nothing’s unanimous, especially with someone as diverse in his views as Dr. Silber,” says Radin, a former longtime Boston Globe reporter and now director of global operations and communications at Brandeis University.

“Nothing’s unanimous, especially with someone as diverse in his views as Dr. Silber,” says Radin, a former longtime Boston Globe reporter and now director of global operations and communications at Brandeis University.

Thus began the long and combative relationship between Silber and BU’s primary student newspaper. “His attitude toward the Daily Free Press was contemptuous,” Radin says. “But I think a lot of people might say that was his attitude toward a lot of things. I think it would be fair to say that almost everything about BU irked him when he was new.”

Over the course of 32 years as president and chancellor, Silber’s every move was Freep fodder, from the cost of items purchased for his home to battles with deans and faculty to allegations of the sale of law and medical school admissions to the collapse of Daniel Goldin’s appointment as president, which had been backed by Silber.

“In terms of the student press in general, it was a pretty hostile atmosphere,” says Stephen Kohn (SED’79) 1976-77 Student Union president and a founding editor of the b.u. exposure, which began as the Student Union newsletter in the mid-1970s. “The administration shut down every student publication sponsored in some way at the University that did not have a censorship rule.” Perhaps that experience helped define Kohn; he is now a civil liberties attorney specializing in whistleblower protection at the Washington, D.C., law firm Kohn, Kohn & Colapinto.

The b.u. exposure, along with the Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts, sued the administration in 1977 for violating First Amendment rights by withholding funding in response to critical coverage (the suit was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount). Howard Zinn, a College of Arts & Sciences professor emeritus of political science, who was the faculty advisor for the exposure, to this day considers Silber’s approach to free speech on campus paternalistic at best: “His attitude was the student press should not be hostile to the administration.”

After Silber had been president 10 years, Radin, by then working at the Globe, drew the assignment of scrutinizing Silber’s tenure. Radin’s six-part series enraged Silber, who describes the coverage as “libelous and inflammatory and seriously harmed the University.”

“Silber tried to have me fired,” Radin recalls. “And the ombudsman put me through the wringer for months, but in the end he said the reporting was kosher. For years after that, Muriel Cohen, a great education writer for the Globe, who passed away a couple of years ago, would say, ‘Oh, Radin, you jerk, every time I have to go to BU and talk to Silber, I have to listen to him rant about you.’”

In the mid-1980s, Radin bumped into his old nemesis at a lecture; they literally backed into each other as they were taking their seats. Instead of glaring and walking off, the two decided to bury the hatchet. They now get together regularly. “I grew up and he got older,” Radin quips.

While Radin and Silber have made up, the Daily Free Press still harbors strong feelings of battle honor when it comes to Silber, if its office walls are any indication; over the years, many of the old framed and mounted front pages have featured stories critical of the Silber administration.

BU Today recently asked Silber how the Daily Free Press shaped his view of the University during his more than three-decade tenure as BU president and chancellor, and why a self-described “open and avowed liberal” came to be viewed by BU’s student press as the mortal enemy.

BU Today: Do you still read the Daily Free Press?

BU Today: Do you still read the Daily Free Press?

Silber: I still do on occasion. Unfortunately, it’s no longer delivered to my office so I do not routinely see it. I don’t see it often enough to have any opinion on its coverage.

How would you characterize your relationship with the DFP during your tenure? Were you treated fairly?

My relationship with the DFP during my years as president and chancellor had its ups and downs. Some editors treated my administration with extraordinary fairness, even though they were often critical. Other editors made no pretense of objectivity but simply echoed the attitudes of the most virulent and irrational members of the student body, calling for revolution now and rejection of all responsible authority.

When I arrived at Boston University in 1971, I soon found that we were on the verge of bankruptcy and the Bank of New England was threatening to call our loans. I had to make drastic cuts. All this was in the interest of students, faculty, staff, and alumni. But the Daily Free Press didn’t care to recognize the financial realities. Their editorial stand was that it was my job to raise the money even though after serious efforts to do that, I found that alumni and foundations were not prepared to put good money after bad in the conviction that Boston University was going bankrupt. The DFP always sided with faculty members who engaged in the crudest forms of demagoguery.

I came to Boston with seven children, four in preschool or just beginning school. They needed a yard to play in, and I had the least expensive fence built around our backyard; plywood, nothing fancy. The DFP delighted in reporting faculty objections, including a claim by one faculty member that I had built an Olympic-sized swimming pool behind that fence. The Daily Free Press never sent a reporter to examine the backyard and expose this false charge, even though I publicly offered on several occasions a $10,000 prize to any faculty member who could find the swimming pool.

When there was a fire at our home shortly after we moved in, most of the things we valued most were still in the basement. That included all of the work I had done as a studio art student, including a portrait of my grandmother and paintings by friends. A collection of records, including early Caruso and Galli-Curci records, were destroyed, along with family photographs — irreplaceable treasures. A short-pants Marxist associated with the Free Press pontificated, “Since property is theft, whatever Silber has lost is something he has stolen.”

I could continue this litany, but you get the point. There was no reason why I should have respected those in charge of the Daily Free Press at that time. They made no gesture in the direction of fairness, no effort to understand issues facing the University or to report on the improvements that were being made.

There were other editors who were quite fair-minded. And there was one splendid cartoonist who prepared a book of cartoons early in the Daily Free Press under the pen name of Matchstick. I still have a copy of his collection. They were splendid, often poking fun at me, but in ways that were perfectly fair-minded. In those days, I always looked as if I needed a shave. In one cartoon I was standing on some makeshift matchbox with all my wrinkles and my beard in full display, saying to a bewildered student, “That is my refutation. What is your feeble response?” That was both funny and fair.

As president, did you read the DFP every day? How did the paper affect your views of campus?

When I was president, I read the DFP every day. And every now and then, the DFP had an article about something that was badly managed at the University — for example, a problem with elevators or food service. In response to what I thought were reasonable complaints, I did my best to take remedial action. In response to complaints about food service, for example, I canceled our system of providing food for students in-house and outsourced all programs. This greatly improved the quality of food and increased students’ satisfaction.

How do you see the role of the student press at a university?

A student newspaper should not function under the illusion that it is the natural enemy of the administration or that, as students still growing up and becoming educated, they are already more competent than the administration and can direct the University and determine its policies. When they behave like typically rebellious teenagers in opposing not only administrators, but authority in general, they demonstrate an immaturity that disqualifies them for the pretentious role they sometimes like to assert. The best student newspapers avoid such excesses and even show some respect and affection for the institutions they attend. If the DFP had a proper function in the context of the University, my presence or absence would have made no difference.

A university’s mission is to educate. What do you think your adversarial approach to the student press, and the media at large, taught young people at BU?

I did not position myself as an adversary of the student press. The student press picked me as their adversary, along with presidents at almost every campus in the nation. Students should be responsible. When they are irresponsible, they should expect to be challenged and corrected. Unfortunately, at the time I came, in 1971, students all over the country were intoxicated with the search for power. This led them to believe that all persons in positions of authority were their adversaries.

I came to Boston University to be their teacher. My job was not simply to be an academic officer of the University, balancing budgets and trying to recruit ever more distinguished faculty. I was there to educate. When students said things that were ill-informed or illogical, I made it my point to correct them. That’s a teacher’s job.

Some people say you are, in fact, a closet liberal when it comes to the role of media, but that you couldn’t resist baiting them, that you enjoyed jousting.

I wasn’t a closet liberal. I was an open and avowed liberal and still am. In 1956, I put my untenured faculty position on the line at the University of Texas in support of integration and the right of a black soprano to sing in a taxpayer-supported performance of Dido and Aeneas. I had four children at the time and major financial responsibilities. I openly organized the Texas Society to Abolish Capital Punishment and testified on the issue with Harvard Professor Larry Tribe before the Massachusetts legislature in 1971. My writings on education reform led to my appointment to the committee designing Operation Head Start. I have no idea what you mean when you suggest that I was a closet liberal. I have worked openly and publicly for education reform all my adult life.

I didn’t go out looking for a fight with the media, but I don’t believe it serves any purpose to remain silent and let bald-faced lies pass for truth. That may be a stupid position from a public relations standpoint, but it’s the one I’ve taken all my life and I don’t intend to change it.

If you are a First Amendment champion, how do you explain the perception that you made it difficult for the student press? For example, former b.u. exposure editorial staff claim you withdrew funding and implemented a prior-review policy that amounted to censorship.

The claim that I made it difficult for the student press is simply a straight-out lie. As long as the DFP accepted money from the University, we could be held responsible for what they published. And they often engaged in defamatory statements about people in Massachusetts. The University couldn’t afford to take on lawsuits on behalf of the DFP. I explained to their editorial board with great care that I didn’t give a damn what they wrote; I had no desire to censor them as long as I was not in any way responsible for what they wrote and published. Where did the lie come from that I denied financial resources to the DFP? I made plain that they could operate as a University-sponsored student newspaper with adult supervision or they could become a totally free press, but they couldn’t have it both ways. The best student newspapers always insisted on their independence and refused financial support.

Once you retired, the Daily Free Press lost its nemesis and perhaps some of its steam. What does that say about the DFP and about you?

By taking the editors and contributors to the DFP seriously, I tried to direct their attention and coverage to facts they often overlooked and offer new perspectives on some of the issues. The attention I paid to the DFP was in my opinion a substantial compliment. Perhaps the administrators who followed me don’t believe paying attention to the DFP is worth the time, and they may very well be right. Unfortunately, I was trapped by the habits of a lifetime. I was a teacher and could never resist the Socratic temptation to seek the truest account of issues and to question those who seemed to me misguided.

But a more important factor may be this: students all over the country have lost their fantastical belief that by outrageous behavior they can take over the university by force. They have now become more responsible. When student newspapers no longer make the administration their primary target, they naturally do not attract the attention they did before.

What did the Free Press get right?

Occasionally, the DFP got things right. And I usually wrote to compliment them. As I said, they had a brilliant sequence of cartoons that gave me much pleasure and satisfaction. They also offered helpful information about policies that went wrong, issues of scheduling, campus safety, inability of faculty to produce grades in a timely fashion, and other problems. I’m pleased about that.

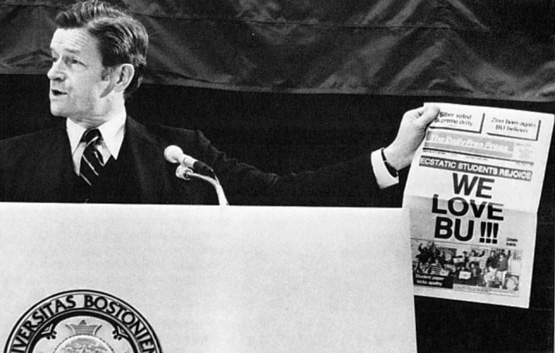

You and DFP founder Charlie Radin (right) had a combative relationship, but now are fond of each other. Can you explain the evolution?

You and DFP founder Charlie Radin (right) had a combative relationship, but now are fond of each other. Can you explain the evolution?

I was introduced to Charlie Radin at the first Senior Breakfast, where he got up to try to persuade all the graduates to refuse to buy caps and gowns and to attend graduation in their disheveled outfits. He proposed that the $5 that would have been used for caps and gowns be given to a charitable organization in Boston.

In response to his remarks I said that I applauded their decision to give funds to the organization they had selected and that I hoped each of them would contribute $5 to that cause. But I added that it didn’t have to be the same $5 that would be used for the cap and gown. I suggested, “Just don’t use your car for a week and you’ll save $5 in gasoline. Or don’t get a haircut. That’ll save some money.”

No male students cut their hair in those days; it was a joke. Very few laughed because in those days students had very little sense of humor. I said, “Now let’s get to the heart of the matter. Your parents have paid tens of thousands of dollars to educate you at Boston University. They and your grandparents and aunts and uncles are going to be here to observe a ceremony that has its origins in the Middle Ages. They have a right to expect to see you in caps and gowns along with the faculty and the administration. You owe it to them to be properly attired.” I’m pleased to say the students heeded my words.

Charlie Radin was a firebrand, but an intelligent, serious young man. I disagreed with him, but that did not mean I held him in contempt. He went to work for the Boston Globe and did a series of very damaging articles on me and the University. I think there is no doubt that those articles were libelous and inflammatory and seriously harmed the University. But I condemned the Globe for having used them, rather than Charlie.

Over the years Charlie matured and became an increasingly responsible, thoughtful person whose journalistic efforts I can only applaud. The evolution of our relationship is not unusual. It is characteristic of the relation of father figures and teachers to their children and students. When adolescents grow up, as Mark Twain observed, they are astonished at how much the old man has learned in the intervening years.

Want to share your thoughts about this story, or any part of the Daily Free Press series? Leave a comment below, or even better, go on the record and be featured in our feedback gallery. You can e-mail us and we’ll get back to you for an interview. Or Skype us (leave a voice mail at “bu-skype-1”). We’ll share your responses ASAP.

Caleb Daniloff can be reached at cdanilof@bu.edu.

Read more from the Freep series.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.