Zhao Ziyang’s Secret Memoirs

Book’s editors on lifting a veil from Chinese politics

Secrecy has long been the calling card of China’s Communist Party. When important leaders retire, unlike their Western counterparts, they choose silence over the attention and danger of a tell-all memoir.

Until now. The first behind-the-scenes look at China’s political power struggles in the turbulent 1980s has emerged, the secret memoirs of Zhao Ziyang, the fallen party chief who spent the last 16 years of his life under house arrest.

“This is an important voice, an important viewpoint, that had been censored,” according to Adi Ignatius, editor in chief of the Harvard Business Review and a co-editor of Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang (Simon & Schuster, 2009). Coming four years after Zhao’s death, the publication “ensures that Zhao’s voice is one that Chinese people have in their heads as they think about what they want for their country.”

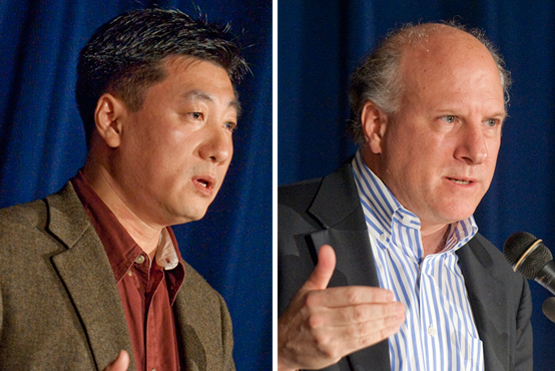

Ignatius was at BU Monday afternoon to give at a lecture with fellow editor Bao Pu (Bao’s wife, Renee Chiang, is also credited) at the George Sherman Union. The event, hosted by the BU Center for the Study of Asia and moderated by Joseph Fewsmith, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of international relations, marked the first time Bao, a human rights activist and the publisher and editor of New Century Press in Hong Kong, has spoken at an American university.

“Historians will think of Zhao’s memoir as required reading,” said Shelley Hawks, a College of General Studies lecturer in social science, who organized the event. “I think it will take its place beside the memoirs of Khrushchev or Gorbachev.”

Monday’s turnout is an indication that the book already has created a stir in BU’s Asia circles, six months into print. An audience of about 60 attended, including professors, students, and a local alum, who said she returned to campus for the lecture after debating about the book with her Chinese friends.

On May 17, 1989, China’s highest ranking officials gathered to decide how to handle student protesters occupying Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The result was a violent military crackdown that ended the political “opening up” China had experienced in the 1980s.

That secret meeting also marked a turning point for Zhao, considered a pragmatic crafter of free-market economic reforms, according to Bao and Ignatius. Seen as an advocate for peaceful negotiations with the protestors, Zhao was labeled a troublemaker, purged from the party, and forced into house arrest until his death in 2005.

“This shows that there could have been another way in 1989,” Ignatius told the gathering.

Getting Zhao’s alternate vision to publication was no easy feat. The process began around 2000, when Zhao started recording speeches about his experiences on cassette tapes. With his house surrounded by guards, he played music to cover the sound of his voice, then hid the tapes among his grandchildren’s toys, Ignatius said.

Zhao smuggled copies to trusted friends in Hong Kong, including Bao Tong, Bao Pu’s father and a close advisor of Zhao’s, who spent seven years in prison for counterrevolutionary activities after the Tiananmen massacre.

Bao went to work translating his father’s copy of the tapes and approached Ignatius about contributing to the project in 2008. They collaborated using encrypted e-mail, Ignatius said. They were afraid the Chinese government would quash the tapes’ release.

Prisoner of the State was finally published in May, just weeks before the 20th anniversary of Tiananmen.

Although scholars characterize Zhao as more policy wonk than charismatic leader, he was a crucial observer of the major ideological struggles that plagued China in the second half of the 20th century, Bao told the audience.

“Zhao saw a period of time when Chinese leaders were engaged in a debate about what post-war China was going to be,” he continued. “Our life in the past 20 years has changed, and that debate has something to do with the change.”

Americans often see political memoirs as campaign tools or self-serving polemics. But in China, according to William Grimes, director of the Center for the Study of Asia and a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of international relations, Zhao’s memoirs have caused commotion for historians and citizens alike. The book has sold 100,000 copies in Hong Kong alone. In mainland China, where the government has forbidden its publication, illegal copies have spread online.

“It’s breaking open the wall of secrecy no one could penetrate,” Grimes said. “As far as I’m aware, it’s the only memoir of its kind” to be written by a high-ranking official in the Communist Party.

Prisoner of the State’s publication, the authors said, shows how much the party has changed since the Tiananmen crackdown. In the past, Chinese officials would go to great lengths to minimize exposés of party turmoil by issuing denials or stifling critics. Zhao’s memoirs have been met with silence.

“Our assumption was that the authorities would squeeze Zhao’s family,” Ignatius said. “But there has been no retribution of any kind.”

Bao, however, remains wary about returning to China after his U.S. book tour ends. “It looks like it’s going to be a difficult process,” he told the crowd.

And while some young Chinese are aware of Zhao’s political legacy, they are far from confident that his memoir will trigger another thaw.

One sophomore majoring in international relations, who was born in China the year of the Tiananmen massacre, was among those who attended the event; he asked several pointed questions of the speakers. But, apparently fearing retribution from abroad, he did not want to be identified.

“A small proportion of students are showing interest in acquiring this knowledge,” he said. “It’s still not something you can talk about openly.”

Katie Koch can be reached at katieleekoch@gmail.com.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.