A Military Man Calls for Cutting the Military

Andrew Bacevich’s new book: United States can’t be the world’s cop

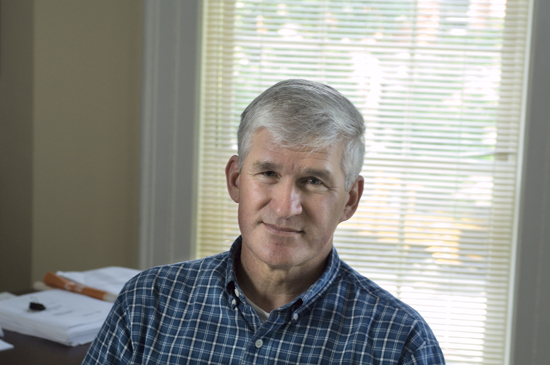

Andrew Bacevich is Catholic, but the “Sacred Trinity” he writes about in his new book is not the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The College of Arts & Sciences international relations and history professor is instead referring to what he calls the three tenets of U.S. security policy: a military stationed around the globe, configured to project its power globally, and charged with intervening anywhere, against threats real or perceived.

In Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War (Metropolitan Books, 2010), Bacevich says these unquestioned principles have produced little security to justify their enormous costs, both financial and human. A former Army colonel and West Point graduate, the author writes from personal experience: his son, Andrew (CGS’01, COM’03), an Army first lieutenant, was killed in Iraq in 2007.

Bacevich, a self-described conservative critic of current military policy, proposes a new trinity: first, use the military to defend the United States and its vital interests, rather than police the world. Second, withdraw troops from places such as the Persian Gulf and central Asia. Third, disavow George W. Bush’s preventive war doctrine (sanctioning an American attack on a potential foe that hasn’t attacked or readied an attack on us) and fight only in self-defense, and as a last resort.

BU Today talked with Bacevich about his proposals and their implications for handling crises ranging from terrorism to humanitarian disasters, such as the 1994 ethnic slaughter in Rwanda.

BU Today: You call for cutting the U.S. military to just the forces needed for self-defense. Define “self-defense.”

Bacevich: There’s room for argument about what self-defense requires, and I’d like to see the argument engaged in by the American public and leadership. The point is to challenge the common practice and expectation that global policing defines the mission for the armed forces. That purpose vastly outstrips the capabilities of U.S. forces and implies demands on our resources as a nation that we are unwilling and probably unable to provide. I can make an argument that in the late 1940s or 1950s, when the strategy was containing the Soviet empire, that approach made a certain amount of sense. But it’s foolish to assume principles defined in the 1940s remain relevant today.

You advocate withdrawing from the Gulf and central Asia. What would prevent a terrorist group from securing a haven in a weak state, as in Afghanistan before 9/11?

It’s the famous question Stalin asked about the Vatican—how many divisions does the pope have? How many divisions does Osama bin Laden have? He can command some number of followers, but what I find preposterous is the notion that this has such appeal to the Islamic world that it can prevail. Al-Qaeda is more like the Mafia than Nazi Germany. An international police effort would have to be sustained, very well resourced, and ruthless to root out this network. Could that involve stationing small numbers of U.S. troops somewhere? Yes. But that gets into tactics rather than strategy. It’s in the realm of strategy where we’re desperately in need of debate.

Would pulling back allow us to prevent, for example, another Rwanda?

People tend not to take on board the costs involved in trying to save other people. Somebody’s kid has to get on the C-17, and some of those kids are going to get killed. And the loudest voices calling for a humanitarian response aren’t necessarily the same people encouraging their children to go see their local Army recruiter. Beyond that, I would hope others, notably the Europeans, would take on a greater share.

The Europeans failed miserably in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Rwanda.

There’s a need to encourage the Europeans to spend more on security capabilities. As long as we shoulder those responsibilities, why should they spend more? The U.S. military presence in Europe is unnecessary and redundant. We should, over maybe a decade, gradually disengage from NATO and convert NATO into a European security arrangement.

There are times when, in response to horrific events, there’s an obligation to intervene, and Rwanda certainly met those criteria. That said, we should recognize that you can stop the killing, but it doesn’t follow that you’re going to eliminate the conditions that led to the killing.

Would a draft make the public less willing to have a huge military projected all over the globe?

Probably the result would be a bit of a brake on the inclination to intervene. But there is zero likelihood that conscription’s going to be reintroduced. The military doesn’t want conscription, students at Boston University don’t want conscription, the parents of the students don’t want conscription.

You’re hard on Bush’s doctrine of preventive war.

Say that the Japanese carriers are about to launch bombers to attack Pearl Harbor. In that circumstance, nations have a right to defend themselves preemptively. That’s not the circumstance that existed in 2003 in Iraq. It’s important to distinguish between preemptive war and preventive war, the one legitimate, the other illegitimate and stupid, as the events of the Iraq war suggest.

Rich Barlow may be reached at barlowr@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.