Fickle Friends: Pakistan and the United States

Four CAS experts discuss how to smooth the way forward

Pakistan and the United States have been allies since 1947. Notthat you’d always believe it. The partners in the War on Terror (now officially dubbed the Overseas Contingency Operation) seem to swing between affable accords and stinging rebukes. Pakistan can be praised for sending troops into tribal frontiers, then blasted for playing nice with terrorists; the United States thanked profusely for sending billions in aid, as its flag is torched on the streets of Lahore.

Is it time for the United States to leave Pakistan alone or strive harder to help it shape a more stable future?

From a Pakistani-born advisor to the United Nations to ascholar of Muslim cultures to the director of women’s studies, some of the international relations experts at the College of Arts & Sciences give their take on what comes next for Pakistanand the United States.

Adil Najam, director, Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future and professor of international relations and of geography and environment

“As with any other messed-up relationship, you have to start by asking not only what the other person did wrong, but what you did wrong.”

The United States and Pakistan need therapy, according to Adil Najam. He can’t decide if the two nations remind him of an interminably divorcing couple or perpetually misunderstood teenagers—“You just don’t get us”—but either way, he says, it’s painful to watch.

“It’s a relationship based on a long history of mutual distrust,” says Pakistani-born Najam. While Pakistan complains of being exploited by the United States, first to help take down the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s, then the Islamic militants, the United States wonders about an ally that accepts its money, but keeps turning out anti-Americanterrorists.

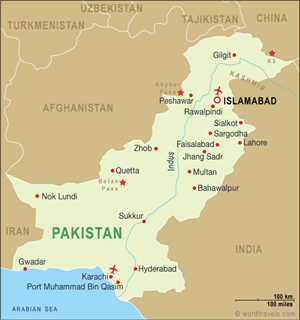

Najam says this suspicion is the natural result of a transactional relationship focused on short-term targets; the two countries concentrate “on their immediate interests with no attention tothe longer range.” Forget the troubles plaguing Kashmir and Waziristan,successive Pakistani governments just want to survive—in a “crushed economy,” he says; they “need a cash daddy.” The United States, he adds, only rides into town when it wants enemies smashed or troops moved (75 percent of supplies for the Afghan front line travel over or through Pakistan).

And when the transactions go awry, when drone strikes pummel remote villages or a faulty bomb is driven into bustling New York City, both countries, from government officials to local media, are quick to blame the other. “For too long, everyone’s been trying to pass the buck,” says Najam, a member of the United Nations Committee on Development Policy.

Perhaps the marriage can be saved, however: “I think for the first time in 30 or 40 years, there is a real seriousness amongst the powers in both Pakistan and the United States to mend the relationship,” says Najam. Rather than just dictating tactics for a war on terror, the Obamaadministration is talking trade, energy, and sustainable development; Najam calls them the “common goals and interests” of a long-term relationship.

The alternative to a trusting partnership is bleak: 8,600 Pakistanis were killed in terror attacks in 2009, while many Americans have grown wary of Pakistanis and Muslims. “The stakes are really the safety of the planet,” Najam adds with a flash of the drama that made him a star talk show host in his native country in the 1980s.

“With all this displacement, with all this dying, there’s a generation building up with distrust, even hatred,” he says of those affected by the war raging in northwest Pakistan. “A different government you can deal with, but a generation with a mindset of distrust, you cannot.”

Andrew Bacevich, professor of international relations and history

“We need to consider the possibility that there are some problems the United States can’t fix.”

The best defense might be, well, defense. If the United States thinks the way to defeat jihadism is with bigger guns, says retired U.S. Army Colonel Andrew Bacevich, the only thing it’ll gain is a couple of zeros on its budget deficit.

Bacevich, author of The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism, takes a dim view of the current U.S. approach in Pakistan: “I think the West has pretty much bollixed it up across the board,” he says.

He argues the United States shouldn’t be throwing money and “American hard power” at Pakistan and Afghanistan, but should “erect effective defenses,” starting with improved surveillance and border control for the West, not just the United States. In becoming an “exemplar, not a crusader state,” the United States can show that it’s not “engaged in some sort of effort to twist their way of life” into line with its norms.

“There needs to be greater attention to demonstrating that the liberal values we profess to represent are not necessarily antagonistic to Islam,” says Bacevich. “We need to live up to those values and help people in the Islamic world come to the realization thatwe are not their enemies.”

And so, while the Muslim world struggles “to reconcile the demands of modernity with the imperatives of Islam,” the United States should acknowledge that its ability to offer a solution to the region’s problems is limited.

“The people best equipped to solve the problems of the Islamic world are the people who live there,” says Bacevich. “Imagine that. What a concept.”

The conservative commentator sees a Pakistan hampered by problems—government institutions that “lack legitimacy,” an overbearing security community, unsatisfactory schools—that the United States doesn’t have the resources or goodwill to fix.

“If you were a Pakistani, why would you have trust and confidence in the United States?” wonders Bacevich. “We have professed to be friends with Pakistan when it’s convenient for us…and when it’s not convenient, we have basically had little to do with them.”

While he believes the United States and other Western powers are unlikely to see the error of their ways when it comes to relations with Pakistan, Bacevich does think we have a tendency to worry too much aboutthe threat we’re facing from the greater Middle East.

“To some degree, we overstate the problem,” he concludes. “Our existence is not threatened by the Islamic world or by hostility in the Islamic world.”

Shahla Haeri, associate professor of anthropology

“The United States should be a little more humble, more understanding in its relationship and expectations.”

Midriff-baring fashion trends, 24-hour food networks, a vibrant music scene. Pakistan has more in common with the United States than people might think, according to Shahla Haeri, the author of No Shame for the Sun: Lives of Professional Pakistani Women. With one possible exception: “The cinema is not good because it can’t compete with Bollywood,” she adds lightheartedly.

Iranian-born Haeri has spent decades studying the culture of Pakistan—she has produced reports on the country for the UN and the American Institute of Pakistan Studies—and says the United States has much to gain by pushing its understanding of the region beyond religious fundamentalism. “Here in the United States we see Pakistan as a homogeneous society with a monolithic political system, but it is a highly complex, multilingual, multiethnic, and fractured society; I hope to get that critically looked at,” she says.

Until the United States deepens its view of Pakistani society, argues Haeri, it’ll continue to make misjudgments in its dealings with the country. When the White House publicly upbraids high-profile officials, for instance, it offends valued regional behavior protocols. Although Haeri believes many Pakistanis “do want the United States to be involved,” such slips are “undiplomatic, and upset a public” that’s increasingly skeptical of current American intentions.

Some contend that Pakistan is quick to blame the United States for allits problems, but Haeri, a frequent reader of the English-language Pakistani press, sees more “well-thought-out, self-critical analysis” there than in the States. She notes that after the failed Times Square bombing attempt in May 2010, the American media consistently traced the problem back to Pakistan.

Haeri remains in regular contact with colleagues in Pakistan, and although recognizing the country is beset by myriad problems, doesn’t get the impression of a backward country seething with insurgents. In writing No Shame for the Sun, Haeri admits she feared she’d see “oppressed and wimpish” Pakistani women subjugated by men; instead she found many to be “amazingly confident, active, articulate, and opinionated.” This window on “the other images of Pakistan” reaffirms the wider lesson. According to Haeri, if the United States can shake up its view of Pakistan, the American public might show more support for a country that shares “its diversity of people, traditions, rituals, and food.” Pakistanis, too, might see an understanding ally, rather than the ogre vilified by anti-American extremists.

The mercurial diplomatic relationship between the two countries presents “a very difficult and intractable problem,” says Haeri, but if we can “pay more attention to the civil society, to people,” there might be reason for hope.

Moeed Yusuf, South Asia advisor, United States Institute of Peace

“The U.S. and Pakistan governments have not been forthcoming about the real nature and extent of their relationship.”

It’s a negotiating tactic, and Pakistan and the United States have it down to a fine art. Some well-placed bluff and bluster to get what you want.

According to the South Asia advisor at the United States Institute of Peace in Washington, D.C., Moeed Yusuf (GRS’04), the two countries bad-mouth each other in public—U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton told CBS’s 60 Minutes in May 2010 that the Pakistani government leaders were “more focused now than they have been, but we are still notsatisfied”—so when they bargain in private, they can “show there’s a lot of public pressure against the other side” and win “more concessions.” It’s also a vote winner.

“They gain political mileage,” says the Pakistani native and former Pardee Center fellow. “Obama is a Democratic president; he has toshow he’s not weak. The Pakistani government needs to show it’s as strong as Musharraf was.”

But when both countries “exaggerate the other’s problems and understate what they’re doing to make things worse,” they leave their relationship hanging by a thread and foment hostile public opinion. The effect is especially dangerous for Pakistani-Americans, says Yusuf: “That’s serious…more scrutiny, more profiling.”

He describes that thread in the relationship as being Afghanistan, but says “there is so much potential commonality in this relationship, which neither side has explored.” He gives improved trade as an example of something that could make relations “sustainable over the long run”: give Pakistan more market access and its economy will prosper, bringing greater stability. “Pakistan, despite what everyone issaying, is the single most moderate Muslim country,” contends Yusuf. “To get a moderate Muslim country on your side…is a big opening for the United States into the Muslim world.”

The United States, he says, needs to cut out the “hard-hitting rhetoric,” while “frequent high-profile visits can seem like they’re trying to micromanage Pakistani politics.” Pakistan, in turn, has to drop the conspiracy theories: “The U.S. president doesn’t get up in the morning and think, ‘How are we going to take out Pakistani nukes?’”

Both sides should instead concentrate on their common enemy—the extremists—and “figure out why the other side is not doing what they want them to do,” rather than publicly lambasting each other. Yusufnotes that he has seen some improvement; the United States, for instance, has released more statements in support of the Pakistani government.

He adds that there’s one potential game changer, too—Kashmir.Pakistan and India have disputed each other’s claims to the territory, often through the barrel of a gun, since the 1940s. If the United States can “show sincerity” in solving that intractable problem, it “would really change hearts and minds.”

This story originally appeared in the fall 2010 issue of Arts & Sciences.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.