A Trip Down Automobile Row

Commonwealth Avenue was Boston’s original Auto Mile

From the bookstore where you buy your required reading to the supermarket where you get your spinach, Commonwealth Avenue was once the place to shop for Oldsmobiles, Studebakers, Chryslers, and many other cars.

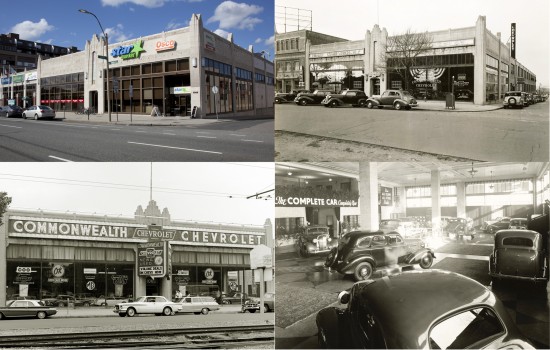

The Kenmore Square building that now houses Barnes & Noble at BU was home to a dealer of Peerless automobiles. The Star Market by Packard’s Corner was once a Chevrolet dealership. And in between lay more than a mile of storefronts selling cars, parts, and accessories or repairing cars. In the 1920s there were more than 100 such businesses on and near that strip of Comm Ave. Downtown Boston had its “Piano Row” and its “Newspaper Row.” This was Boston’s “Automobile Row.”

During the latter half of the 20th century, BU bought and repurposed many of these buildings. The College of Communication took over 640 Commonwealth Avenue, where long-forgotten Nash vehicles were sold for three decades. At 590 Comm Ave, General Tire and Exide Batteries gave way to the Metcalf Science Center.

Look carefully, and you can still see signs of the area’s former life. Buick Street. The Packard Building. The scallop shell sculpted into the façade of the BU Academy—a shell that looks not-so-suspiciously like the Shell Oil logo. The miniature mechanics and motorists who gaze down at student artwork from pillars in the College of Fine Arts. On every block now dominated by Boston University’s Charles River Campus, an astute observer can find traces of its automotive past.

The prince of Packard’s Corner

Born in 1878, Alvan T. Fuller was a champion bicycle racer, who at age 17 started a bike shop in his hometown of Malden, Mass. After the turn of the century, he decided to bank on a more expensive form of transportation: automobiles. Fuller convinced the Detroit-based Packard Motor Company to name him its exclusive dealer in the Boston area.

By 1908, Fuller believed the motorcar business was about to outgrow the cramped confines of central city locations such as his stall in the Motor Mart in Boston’s Park Square. The young entrepreneur looked westward. After decades that saw luxury homes rise in the Back Bay and the Cottage Farm district of Brookline, development had stalled on Comm Ave west of Kenmore Square. Fuller cast his eye on large unbuilt tracts that were close to downtown and accessible by trolley.

The site he chose for his big new Packard dealership was a section of Brighton coincidentally named Packard’s Corner—after the nearby horse stable and riding school run by one John D. Packard. Perhaps, not unlike Eddie Murphy’s character in Coming to America, who travels to Queens, N.Y., to seek his queen, “Fuller may have been tempted to the neighborhood because of the name,” says William P. Marchione, a member of the Brighton-Allston Historical Society and author of four books about Boston.

Designed by nationally known architect Albert Kahn, the building Fuller erected at 1079-1089 Commonwealth Avenue—now home to condominiums as well as Supercuts and other businesses at street level—was New England’s first combined auto salesroom and service station. It included assembly, storage, and repair facilities, as well as offices.

The building’s showpiece, however, was its showroom, designed to appeal to the high-end customers then in the market for autos. “Fuller’s handsomely furnished showroom had high ceilings and fluted columns, and was lit by a combination of elaborate hanging fixtures and a barrel-vaulted skylight,” writes Marchione in Allston-Brighton in Transition: From Cattle Town to Streetcar Suburb.

At that time, an automobile was a luxury few could afford. Often called a touring car, it was something to be taken out for Sunday spins on “pleasure roads” in the country, not driven to Buffalo to see one’s aunt (that’s what the train was for) or to work (trolley lines connected most suburbs to the city). Fuller’s typical buyer was either wealthy, a committed gearhead hobbyist (considerable assembly was required after purchase), or some combination thereof.

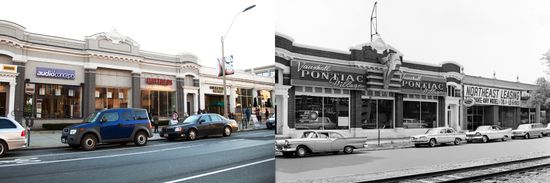

The number of buyers grew in the second decade of the century, and other dealers followed Fuller to Packard’s Corner and vicinity, taking advantage of the big open spaces to build or rent spacious showrooms that were ornate by today’s standards. “These buildings required large expanses of well-lighted garage space and display areas, and floors capable of supporting heavy loads,” writes Nancy Salzman in Buildings & Builders: An Architectural History of BU. “Their façades were often embellished with vigorous and distinctive designs.”

From 1910 to 1920, at least a dozen dealerships opened on Commonwealth and Brighton Avenues, selling models of Auburn, Rolls-Royce, Hupmobile, Pierce-Arrow, Clark-Crowley, and other brands.

It turns out that Fuller started more than a strip of car dealerships; he started an enduring and nationwide promotional trend. By 1917, the car salesman had begun hosting an annual “open house” on George Washington’s birthday, February 22. In those days, people didn’t drive in the winter; the city didn’t even plow the streets. Even in the late fall, ladies going for a ride in the mostly open-air autos were advised to wear velour and fur “motor robes” and woolen caps and scarves, and to bring a foot muff and a hot water bottle for good measure. Once the real cold weather came, “People just put their car on blocks until the spring.” says Edward Ellis, whose family owned an auto accessories store on Comm Ave for decades. Ellis says the winter break begat the savvy used-car shopper’s practice of kicking tires: “Years ago, tires had straw in them, not air,” he says. “If you let them sit in winter, you’d have a flat spot. People used to kick the tires to see if they were resilient and the straw hadn’t resettled.” (Or at least, Ellis adds, that’s what he was told when he started in the business.)

Fuller figured by late February motorists were ready to check out the year’s new Packards. Other dealers followed his lead, offering their own sales and hiring bands and serving cherry pies. “It was a carnival atmosphere on Comm Ave,” says Ellis.

Fuller had become one of the richest men in America, and in 1924, after serving eight years in the state legislature, he won the race for governor, defeating James Michael Curley.

Hallmarks of the halcyon days

On the eve of the Roaring Twenties, the Noyes Buick building was built at 855 Commonwealth Avenue, today home of the College of Fine Arts. The building featured enormous arched windows (now filled in) looking into a showroom with a vaulted, Romanesque ceiling and Corinthian columns. This showroom is now CFA’s Stone Gallery. The next time you visit the gallery, look up at the top of the columns. Instead of traditional gargoyles, you’ll see gargoyle-like mechanics with wrenches and motorists in caps and goggles.

Automobile Row boomed over the next decade. By 1929, there were 117 car dealerships, garages, and other auto-related businesses lining Commonwealth Avenue and spilling onto Brighton Avenue.

More than 20 years after Fuller opened his Packard complex, automobile ownership was within the reach of a growing number of Americans, and Fuller built an imposing Cadillac-Oldsmobile dealership at 808 Commonwealth Avenue—today CFA’s 808 Gallery—across from the BU Bridge (then the Cottage Farm Bridge).

The opulent dealership, also designed by Albert Kahn, was derided initially as “Fuller’s Folly,” but combining sales of the luxury Cadillac brand and the workingman’s Oldsmobile turned out to be a smart move. Mark Lande, a salesman at Herb Chambers BMW, one of Comm Ave’s few remaining dealerships, remembers Fuller’s business in its later and still thriving decades: “The shiny red Cadillac Eldorado, rotating on a turntable, caught everyone’s attention,” he recalls. “But most people purchased the affordable Oldsmobile.”

Daniel LeClair’s office is in 808 Comm Ave, and the Metropolitan College professor’s file room was once the vault (now minus the safe) that held Fuller’s Caddy and Olds revenues. The street-level showroom is essentially intact, and it still attracts a lot of attention, now with student artwork. A remnant of 808’s original purpose remains: a concrete ramp inside the building that makes it possible to drive all the way up to the fifth floor.

A car dealership also occupied the building at 830-844 Commonwealth Avenue, which now houses BU’s Photographic Resource Center and Sicilia’s Pizzeria. Up the street at 860 Comm Ave was a Pontiac dealership, now the Ski Market block.

Diagonally across Comm Ave from 808 is the BU Academy, at 785 Commonwealth Avenue. This building was once the Shell Oil Company’s New England headquarters. Not only are there shells and other aquatic symbols carved into the building’s façade, but at one time a giant neon Shell logo loomed from its roof. Built in 1933, the steel sign was 68 feet high. It still exists—but now lives across the river, at a Shell station on Memorial Drive in Cambridge. (Also across the river from 785 Comm: a former Ford assembly plant. It’s on your right when you cross the BU Bridge into Cambridge.) The Shell building served for a time as a General Tire outlet, before housing BU’s College of General Education, Sargent College, and finally, the BU Academy.

At 1001 Commonwealth Avenue, Ellis the Rim Man was a highly visible remnant of Automobile Row into this century, thanks to its giant billboard. Today the location of Boston’s MATCH Charter School, Ellis carried “accessories” like seat belts, rear-view mirrors, radios, and AC units before those became standard parts of a car right out of the factory.

Edward Ellis discusses his former auto accessories shop, Ellis the Rim Man, and tours the MATCH Charter School, which took over his building at 1001 Commonwealth Avenue. Photo by BU Photography View closed captions on YouTube

End of the road

The Depression was hard on the auto industry all over America. On Boston’s Automobile Row, it closed a third of the 117 auto-related businesses, but the district survived, with at least 54 dealerships and many attendant businesses soldiering on.

In the postwar 1950s, the federally built interstate highway system boosted auto sales, and Auto Row enjoyed another peak. But something else was skyrocketing in this period, thanks to the G.I. Bill: college enrollment. Boston University, scattered across several buildings downtown, had bought the tract of land west of Granby Street and north of Comm Ave three decades earlier. After World War II, BU began to consolidate on the Charles River Campus.

Meanwhile, families were moving to the suburbs, and car dealers followed—to places like Norwood’s Route 1 “Auto Mile.” By 1975, there were only 21 dealerships on Comm Ave, and by 1981, just 11. Today there are but three, all Herb Chambers stores, all beyond Packard’s Corner.

Change has been a constant for the transportation landscape on this stretch of Commonwealth Avenue. Horse-drawn buggies gave way to electrified trolleys, which had to share the road with automobiles. From an environmental perspective, some welcome changes have arrived in the past few years. A joint beautification initiative of BU and the city of Boston widened the sidewalks and planted trees, and the recent addition of a bike lane and the Hubway bike-share program may encourage cyclists to think of the road as theirs as well. Alvan T. Fuller might appreciate the paradox: after all, he started out selling bicycles.

Sources for this story include the works of William P. Marchione, Nancy Salzman, Art Krim, and Keith Morgan. Additional research by Robin Berghaus and Art Jahnke

Patrick L. Kennedy can be reached at plk@bu.edu.

This article was originally published on October 20, 2011.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.