Baseball Greats Reranked

BU study factors in equipment changes, steroids, medical procedures

Red Sox fans will be pleased to know that what they’ve long suspected is true: A-Rod really isn’t as hot as he thinks he is.

That is, according to passionate baseball fan Alexander Petersen. Using statistical physics theory, he’s found a way to compare baseball players over the generations, whether they played in the dead-ball era in the early 1900s or the steroids era beginning in the 1990s. And while his baseball findings will interest fans of the game, the larger patterns he’s discovered across many kinds of careers may have greater implications for measuring an individual’s success relative to others in diverse fields.

These patterns emerged after physics doctoral student Petersen (GRS’11), with H. Eugene Stanley, William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and an Arts & Sciences professor of physics, and Orion Penner (GRS’06), a PhD student at the University of Calgary, “detrended” historical American baseball statistics using power-law probability density functions, which scientists use to understand competition-driven systems. “Basically,” says Petersen, “detrending corresponds to removing the inflationary factor, so we could compare two items like the cost of a candy bar in 1920 to the cost of a candy bar in 2000. In this case, we compare Babe Ruth’s home runs—the ability of someone to get a home run then versus now—and you see Babe Ruth actually hit a lot of home runs on this relative basis.” Petersen’s new statistics compare career longevity, success, and productivity. When comparing the baseball statistics, he was startled to discover a statistical pattern, what he calls a beautiful power-law curve (a type of bell curve), emerging from seemingly random careers.

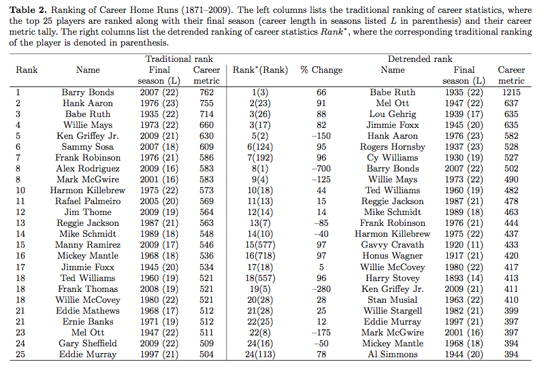

In Petersen’s rankings, found in a paper titled Detrending career statistics in professional baseball: accounting for the Steroids Era and beyond, the recent big-name home run hitters—Sammy Sosa, Jim Thome, Mark McGwire, Manny Ramirez—drop significantly down the list of top hitters throughout history. New York Yankees slugger Alex Rodriguez drops 425 percent, from number 8 to number 42. “The relative significance of their accomplishments gets reduced because their contemporaries are hitting a lot of home runs as well,” says Petersen. Players like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Ted Williams shoot up the list because they were giants in their own era as well as across the decades. Petersen says his approach is a way to make the statistics fairer: besides accounting for the possible effects of steroids, detrending allows for changes in equipment, diet, conditioning, even medical procedures like Tommy John surgery (replacing a ligament in the elbow with a tendon to lengthen a pitching career), all of which have changed the game since Ruth’s time.

Petersen’s work has implications for both historical rankings and Baseball Hall of Fame inductions, but it has even broader implications for human enterprise in general. The power-law pattern that emerged through his detrended analysis of American baseball stats stayed the same when the physicists compared Korean baseball statistics, then those of other professional sports, and eventually data on nonathletic careers, such as academic research. The pattern remained consistent, a statistical regularity across disciplines and careers.

“In every career,” Petersen says, “there are metrics for success and productivity.” And when mapped out, those metrics form a distinct pattern.

“The idea of a statistical regularity is not so hard to understand in the case of the bell curve that quantifies human height,” says Stanley, director of the Center for Polymer Studies, which conducts interdisciplinary research, and Petersen’s advisor. “But any regularity with free will just blows my mind because I was brought up believing everything depended to a large extent on my choices. And now here’s the idea that despite my actions, I just end up fitting into some formula.”

Petersen originally looked at baseball statistics both because he loves the game and because the sport uniquely has meticulously recorded data going back to the 1800s. But although baseball has the most complete data, he points out, when a different type of career is analyzed, a similar statistical regularity appears: “You can quantify it with a law—a law of human success, a law of human productivity.”

Petersen originally looked at baseball statistics both because he loves the game and because the sport uniquely has meticulously recorded data going back to the 1800s. But although baseball has the most complete data, he points out, when a different type of career is analyzed, a similar statistical regularity appears: “You can quantify it with a law—a law of human success, a law of human productivity.”

His data indicate that how well we succeed relative to others has less to do with our own drive and more to do with the drive of those around us, whether on the baseball diamond or in a physics lab.

Rachel Johnson can be reached at rajohnso@bu.edu.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Fall 2010 edition of Arts&Sciences.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.