Bringing the Law to Those Who Can’t Afford It

Robert Spangenberg brings his legal aid group to LAW

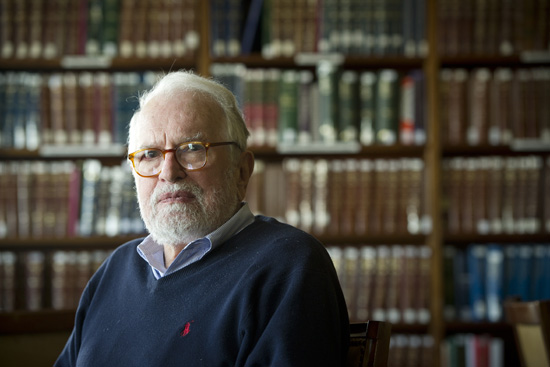

Robert Spangenberg (LAW’61) has spent his career fighting for legal services for the poor across the country and the world. Photo by Vernon Doucette

The day after Robert Spangenberg was named editor-in-chief of Boston University’s Law Review, he got an offer few could refuse. The dean called Spangenberg into his office and told him, as he had all editors before him, that the editing gig would certainly land him a job in a big Boston firm. Which one would he prefer? Spangenberg (LAW’61) thought for a moment. “None,” he said.

The law student had set his sights on a much bigger goal: he wanted to improve legal representation for poor people.

And he did. In the 1960s, Spangenberg worked with the Johnson administration and helped establish the Office of Legal Services, the first federal legal aid program. He later founded and directed Greater Boston Legal Services. In 1985, he started the Spangenberg Group, the only consulting firm in the country dedicated to championing legal representation for the indigent. The group studies the effectiveness of public defender offices and legal aid services around the country and abroad, a practice that has revealed, for example, that the caseload of a public defender in Miami was an impossible 2,000 defendants a year, and that the Pennsylvania court system was so underfunded that poor people were extremely unlikely to find capable legal defense.

Spangenberg, who briefly served as assistant dean at LAW in the mid ’60s, rejoined the faculty this fall. He will recruit BU law students to work with him on some of his firm’s projects such as training public defenders in Mexico.

BU Today spoke with Spangenberg about his career, which naturally led him to work on a number of death penalty cases. As he says, there are no rich people on death row.

BU Today: Why did you return to BU?

Spangenberg: I’ve always thought of BU as my home. Also, the dean and faculty are committed to the public interest. Students are doing a huge amount of pro bono work here. There weren’t any opportunities for doing that when I was here as a student.

What drew you to legal work for the poor?

After college I was drafted and went to Germany. I had a lot of time on my hands and read a lot. I became fascinated by books about law, specifically, a book by Jacob Lefkowitz, a criminal lawyer who worked with indigents. I decided to study law when I got out. I came here and helped form the Roxbury Defenders Project, one of the first such law student programs in the country.

What are some of the dramatic changes you’ve seen in legal help for the poor?

One of the most dramatic improvements is legal counsel in death penalty cases. When I started out there were very few lawyers who could handle a death penalty case. Now there are lawyers in every state who do nothing but that.

Also, when I started out the greatest need was in the South. Half of my work in the past 20 years has been there. But in my opinion, the South has made a lot of progress, particularly Texas, which is doing things that are unbelievable. It’s no longer the sleeping-lawyer, death-valley capital. True, they are still putting people to death, but not nearly as many as they once were.

Do poor people have better access to legal representation today than in the past?

There is still an awful long way to go, but it’s clearly better than when I started out. Money is still the main hurdle. It’s hard to convince the general public to put money into lawyers who are representing people who’ve committed crimes and are poor.

And there are still a lot of misconceptions. In Massachusetts, Governor Deval Patrick, who I hold in high esteem, says having public defenders costs less than using court-appointed private criminal lawyers. That is so wrong. We’re going to end up in a terrible situation in Massachusetts, which has done a good job in providing counsel to the poor, but the system is being taken apart.

With someone’s life at stake, it must be hard to work on a death penalty case.

Definitely. There was a death penalty appeal I worked on in Indiana in the early ’90s. I was an expert witness. I testified and then flew home. I came back and had a message from the lawyer in Indiana that said, “Jones lives.” I just wanted to cry.

Do you think the recent execution in Georgia will have an effect on people’s opinion of the death penalty?

I think it will have a substantial effect. It was widely covered, even internationally. People are now speaking against the death penalty who haven’t spoken up before.

But in a Republican presidential debate recently, when Rick Perry, the governor of Texas, was asked about the number of people that had been executed there, the audience clapped and cheered. So this is not a good time, but it’s a time we need to redouble our energy. And one thing about me is I have a lot of energy.

Amy Sutherland can be reached at alks@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.