Mitchell Zuckoff on Daily Show Tonight

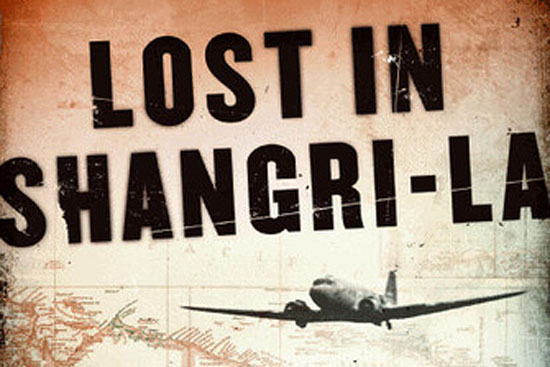

COM prof to discuss World War II tale, Lost in Shangri-La

Mitchell Zuckoff goes head-to-head with Jon Stewart tonight to discuss his suspenseful Papua New Guinea survival tale Lost in Shangri-La: A True Story of Survival, Adventure and the Most Incredible Rescue Mission of World War II.

Zuckoff, a College of Communication professor of journalism, knows a promising story when he sees one. But he concedes that his latest book is an embarrassment of narrative riches, a platter heaped high with heroism, history, human pathos and pluck, and nail-biting adventure.

The book chronicles the May 1945 crash of the Gremlin Special, a plane carrying 13 U.S. servicemen and 11 members of the Women’s Army Corps on an R&R sightseeing flight over a valley frozen in time in the wilds of New Guinea. The wounded survivors were stranded among an isolated tribe, unable to gauge the potential dangers they faced.

A former Boston Globe reporter and author of several books, including Ponzi’s Scheme: The True Story of a Financial Legend, Zuckoff ventured deep in the equatorial rain forest to report the tale, which was widely covered at the time, but all but forgotten now. The story is verifiable thanks to a trove of sources, from the recollections of a living survivor to a declassified U.S. Army report to a diary scrawled in secretarial shorthand.

In spite of a torrent of press accounts in the weeks following the crash, U.S. Army photos, and a crude documentary film, Zuckoff’s elegantly woven narrative is the first book about the events leading up to the ordeal, the trials faced by the two men and one woman who survived, and their fate after the story faded from the headlines. The bulk of the book is devoted to the grueling, poignant, and ultimately redemptive story of three decent, gentle souls, and Zuckoff admits to falling in love with each of them. Published in April by Harper Collins, Lost in Shangri-La has earned early praise from both Kirkus Reviews (“Polished, fast-paced, and immensely readable”) and Publishers Weekly (“Zuckoff’s book gives a window on a more romantic and naïve era.”).

BU Today sat down with Zuckoff recently to hear more about what captivated him about the story, his slog through the rain forest, and his views on the increasingly blurry line between fact and fiction.

BU Today: Not all great stories make great books. How did you know you had a winner?

Zuckoff: Yes, some stories are really meant to be magazine articles. But this one had every element I could hope for. Not only was it a remarkable story and rare—a female in a war story, that doesn’t often happen—but it was an anthropological story, too. I could find out what the natives thought when the equivalent of Martians landed on their front lawn. It wasn’t an old pulp fiction tale of heroism in World War II, though those are great fun. I could show the other side of the story, which made it reach the point of critical mass for me, and made me know this was the book I was dying to write.

Margaret Hastings’ diary provides much of the book’s day-to-day detail, yet you didn’t know how helpful it would be when you began your research. Where and how did you find it?

A source like that, it’s what you dream about. Sadly, Margaret died in the late ’70s, but I had this 15,000- to 20,000-word diary of hers, which I found in the Tioga County Historical Society in Owego, N.Y. This wonderful historian, Emma Sedore, had transcribed it from secretarial shorthand. I did know that it was there, but I didn’t know what form it existed in, and Emma couldn’t have been more helpful or kind. It was like she was waiting for someone to walk through the door in this tiny town so she could say to him, ‘Here’s the greatest gift you’ll ever find as a writer.’ It was a well-written and well-crafted narrative.

Your afterword says you took no liberties with facts, dialogue, characters, or chronology. How do feel about nonfiction writers’ tendency to use composites, tinker with timelines, fabricate dialogue, and speculate in fleshing out events?

I hate it with a white-hot passion. I hate the way those authors behave. I believe in nonfiction as that word was intended by the people who first used it. I am such a purist about this. I’m only half kidding when I say my favorite 40 pages of the book are the end notes documenting how I can say what I’m able to say here. Creative nonfiction is an oxymoron. Of course my nonfiction is creative, but it’s nonfiction. These authors do fiction. The reason I hate it so much is I don’t know what to trust. When I’m reading nonfiction, I want to be able to walk away saying, this is true.

What did you learn about journalism at that time from the news reports you used?

The reports were 80 to 85 percent reliable. But this is laughable: one of the heroes of this story was Earl Walter, who parachuted in to rescue them—in every account his name is misspelled as Walters. When you get beyond that, there was some really good reporting done.

Did the news outlets steal from one another?

Oh, endlessly. Some of it was pooled reports; some of it was just the Wild West. Today it would’ve been the Chilean miners times 12. Who would get the first interview with Margaret? One thing I hope we learned is how we would’ve acted toward the Filipino rescuers, who got almost no press attention then. And the tribe—people were happy to see them at the time as one-dimensional. One of the fun parts for me was going and learning about their culture, their view of the world, which was in some ways more interesting than ours.

What was the trip to New Guinea like?

That was wild. I’ve traveled to a lot of strange and faraway places, and this was the most far away. I flew from Boston to Hong Kong to Jakarta to Jayapura, and then another flight on a small plane into the valley, through the same mountain pass where the plane crashed. As we headed toward that mountain, I thought, if my plane crashed, my agent would’ve been thrilled.

Were you scared?

Oh yeah, I’m big enough to say it. Fortunately, when I did land safely, the most important logistical piece of it was that I had someone there to meet me—Buzz Maxey, the English-speaking son of missionaries. He’s one of a handful of people on the planet who speak the language of that New Guinea tribe.

How long did you stay?

I was in the valley for almost two weeks. There’s a little town called Wamana in the central valley, where I slept in a little hotel. The room was fine, I’ve slept in worse, but the bathroom was open to the sky. If I had to go to the bathroom in the night, I could take my shower at the same time. I went in January and February of 2010, though the crash was in May. But there really aren’t seasons in the valley; it’s an equatorial temperate zone. I climbed the mountain, a mile and a half hike, to see the wreckage. I was healthy, had not just suffered a plane crash, and I was exhausted. We had a guide with a machete. There was a moment when we had to go across a single log bridge over a gulley 15 feet down filled with rocks. The log was covered with moss. It was slippery as hell. The guide, Tomas, had cut me a balancing stick, and I was like, I’m going to fall. I’m in pretty decent shape, but I was not prepared to do this. I was going to go on my belly, but Tomas came back across the log and walked me across backwards. It was quite treacherous.

Mitchell Zuckoff in Papua New Guinea, next to the wreckage of the Gremlin Special. Photo by Buzz Maxey

Mitchell Zuckoff in Papua New Guinea, next to the wreckage of the Gremlin Special. Photo by Buzz Maxey

How much has the tribe changed since the end of World War II?

Their lives haven’t changed much. They still grow sweet potatoes and raise pigs; they live almost prehistoric lives in hamlets of grass huts. You do see cast-off western garb, but among older folks, the men are naked except for penis gourds and the women wear straw skirts; younger ones wear T-shirts. We were driving down the road in Buzz’s truck and saw a handsome young man wearing an Obama T-shirt, so we pulled over and I asked him, ‘Do you know who Obama is? That man on your shirt?’ He had no idea.

You write that after the rescue, the Army sent Hastings, the story’s WAC heroine, on a national tour hawking Victory Bonds. Do you feel she was exploited?

I rationalized it by reminding myself that Margaret was still a corporal in the Women’s Army Corps, and the brass decided she was more valuable to the war effort on a bond tour than returning to New Guinea. But her heart wasn’t in it. It was clear to me from reading the speech she gave again and again that this was arduous for her. She had to relive the deaths of her friends. I don’t think she enjoyed that at all, and that’s part of the reason the story disappeared. She was happy to retreat to the shadows. You’re not going to believe this, but there was no obituary for Margaret. She was not even remembered as the queen of Shangri-La when she died.

One striking aspect of the story is how well everyone behaved. Had you hoped to uncover some conflict among the survivors?

You always look for conflict; it’s the nature of what we do. But I was very satisfied with how they ended up behaving, because John McCullom, one of the two male survivors, was such a thoroughly decent man. He’d just lost his inseparable twin in the plane crash and he held it all together, and that became a model for how Margaret and Ken Decker behaved—if McCullom could keep himself together, so could they. They trusted him because he was such a great leader.

You go easy on the Gremlin Special’s pilot, Colonel Peter Prossen, who showed bad judgment in leaving his seat and letting the less experienced copilot fly the plane moments before the crash.

I hope any close reading of the book will show that this was an error. I became friendly with Prossen’s son, who didn’t know that his father had left the cockpit. I got the declassified crash report very early in my research. John McCullom made clear that Prossen was standing in the radio compartment when the crash happened, that he’d left the controls to his less experienced copilot. It was a fatal mistake. One reason I didn’t feel the need to beat up on him was that he paid the ultimate price for that mistake.

Were any of the sources you contacted resistant or uncooperative?

Not one. Not a single person. I called people out of the blue and said, ‘Hi, I’d like to talk about your dead uncle or your dead aunt,” and they sent me all this material. I kept waiting for someone to say, ‘This is a family tragedy, please leave us alone.’ But I kept getting off the phone with the feeling that they were waiting for me to call. They couldn’t have been more helpful and generous and grateful.

What’s your favorite book of this genre?

Ghost Soldiers by Hampton Sides. That was a book I’d read and reread before I got to work on this.

It comes across very strongly in the book that you had a great time researching and writing it.

Yes, the problem with a book like this is, when am I ever going to have this much fun again?

The Daily Show episode featuring COM’s Mitchell Zuckoff airs tonight, June 22, at 11 on Comedy Central.

Susan Seligson can be reached at sueselig@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.