The King’s Speech Boosts Profile of Stuttering

BU speech disorders specialist on accuracy of Oscar-nominated film

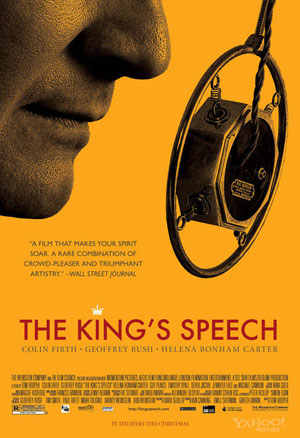

The King’s Speech opens with a painful scene where England’s future King George VI, played by Colin Firth, is standing at a microphone, attempting to deliver a speech before a stadium full of people. The loud echoes of his halting words snarl back at him like a monster composed of disjointed sounds, pure nightmare for someone who stutters.

The historical film is the story of King Edward VIII’s younger brother, a stutterer who is thrust onto the throne after Edward abdicates to marry Wallis Simpson. Not only is George facing more public speaking, but the new king must calm and inspire the English people in the face of Hitler’s advancing war machine. An unorthodox speech therapist, played by Geoffrey Rush, helps the insecure monarch find his voice. The movie was nominated for 12 Oscars on Tuesday, including for Best Film, Best Actor (Firth), Best Supporting Actor (Rush) and Best Supporting Actress (Helena Bonham Carter).

On this side of the pond, stuttering affects about three million Americans, with men suffering three times more than women. Diane Parris, a Sargent College clinical associate professor and codirector of the Joseph Germono Fluency Center at Sargent’s Speech, Language and Hearing Center, says stuttering is a neurophysiological deficit that experts are still trying to pinpoint. “People who stutter have this motor timing problem in their speech muscles, which is probably genetically linked,” she says.

With no cause or cure, insurance companies are reluctant to cover stuttering therapy. Speech devices and drugs have been developed, Parris says, but have yielded limited results. A study published last year by the New England Journal of Medicine stated that three gene mutations may be responsible for about 9 percent of stuttering cases, suggesting that biology is the culprit. BU’s fluency center has been offering affordable treatment to people who stutter for more than three decades.

BU Today caught up with Parris to ask about the accuracy of The King’s Speech and whether the film dispels or reinforces myths about stuttering.

BU Today: How successful was The King’s Speech in depicting the world of stuttering?

Parris: Colin Firth pretty accurately depicted how King George VI sounded because there are tapes you can listen to, the actual speeches are online. But the part that was so amazing and impressive was he was able to convey the fear and inner conflict and angst when he was trying to speak and couldn’t. You could feel his concerns, his concern for the listeners and the listeners’ judgments, the pressure just building in those moments. I thought he did a fabulous job showing the way stuttering impacts a person’s speech, life, and mind, and what they’re capable of doing.

The scene where a doctor has George fill his mouth with marbles was primitive and sad.

That harkens back to Aristotle or something. But even before that, they would cut out parts of the tongue because they knew stuttering had to do with articulation. They put salves on the tongue or did surgery.

What did you think of the techniques used by King George’s speech therapist, Geoffrey Rush’s character?

The kinds of techniques they used in the movie aren’t things we do now. For example, putting a sound before the word as a springboard. We don’t encourage that. It’s a way of avoiding saying the word and we work against those kinds of things. Obviously, the profanity is like a distraction. If you distract a person who stutters in any kind of way, with a sound or at one point George was rocking back and forth on his feet, to facilitate speech, that’s what we would call a trick. It tricks the system. But it doesn’t manage the moment, doesn’t teach the person how to be in charge. And those tricks stop working after a while, too. People adapt to them, so it’s not an effective strategy. But one thing he did do that we’d recommend was he had the king parse his speech, had him phrase in chunks, saying smaller amounts of speech rather than long complex sentences.

While the motor speech piece George’s therapist was doing is outdated, the therapeutic relationship and overcoming and confronting fear and not letting yourself off the hook, all of the ways he related to his client, were well done and beautiful and the kind of thing people are pointing to these days. The therapeutic relationship has to be in place or whatever you teach the client won’t be nearly as effective. I thought that scene at the end was so poignant, when Geoffrey Rush is face-to-face with the big microphone between client and clinician. He is so empathic with his client and he starts mouthing the words along with the king. Speaking in unison has been known to be facilitative in people who stutter.

What treatment methods are effective today?

The things he was teaching King George to distract him from stuttering—we do the opposite. We would say, be highly aware in the moment when you’re stuttering. See if you can even feel the tension levels in your muscles and release some of that tension to move forward. It’s really about muscle movements and not distracting yourself from them.

We talk about it as managing or finessing the moment. If you sometimes try and push through too hard, it increases tension and makes it worse. If they back away and avoid the word, then they don’t say what they want to say and aren’t showing themselves fully, and that’s a problem for people who stutter. They feel like they aren’t able to be who they really are.

The relationship between the king and his wife was admirable and touching. But I’d imagine stuttering can also have a difficult impact on relationships.

Yes, she was rather supportive and saw him as a king despite his speech, which is what any one of us would wish for in a spouse. Stuttering is a family affair. It affects parents as you saw in the beginning of the movie. They felt helpless and weren’t sure how to handle it and just ended up scolding him and dominating the situation. Siblings will feel uncomfortable that they talk better, and they don’t know what do about it and wish their brother or sister would just speak. In romantic relationships, we have all kinds of stories. A man, for example, wanted to ask a woman on a first date, but the phone can be difficult for someone who stutters. So he waited and learned what her patterns of life were, when she left the library or whatever. Then he would “bump” into her so he could invite her out.

I actually have clients in the center who had not spoken with their spouses about their stuttering until they came for therapy. It can be a taboo subject. People don’t want to make their loved ones feel uncomfortable. But it becomes a conspiracy of silence and creates an elephant-in-the-room situation.

What are some of the more persistent myths about people who stutter?

Parents don’t cause stuttering. The situation King George had to deal with as a child, with his parents scolding and his brother teasing, certainly exacerbates the situation. But the problem is fundamentally physiological, even if parents make a mistake and scold. That adds to a person’s shame, which is big concern. People who stutter become very embarrassed. They start to see themselves as defective, rather than someone who has speech problem.

People still get confused about whether to help someone who is stuttering to finish their sentence.

The best thing to do is to listen patiently, give normal eye contact, but wait to hear what the person has to say. Basically, our message to people who stutter is: speak, say what you have to say. Our message to the listeners is: keep listening. You don’t have to fill in their words. People who stutter typically don’t appreciate that.

You sometimes hear stories of people losing their stutter in certain situations, like a radio announcer becoming fluent once the microphone is turned on.

There are some paradoxes that are difficult to explain. An actor playing a different role can be completely fluent. When someone sings they can be completely fluent. Maybe they’re managing their speech muscles a little differently. The most striking example: we had a client who was bilingual in Russian and English, and he said, “Diane, I will speak fluently in Russian unless someone in this room tells me that they understand Russian or a Russian speaker comes in, and then I will be equally disfluent in both languages.”

So there’s something unique in this interaction between human beings that’s completely different from when you are talking with yourself, or no one understands, or you’re talking to a nonjudgmental child or to an animal. People who stutter say they don’t stutter in those circumstances. The interaction and worry about the listeners’ judgments is a fundamental issue for all human beings, but for sure for people who stutter. The fear of judgment is extraordinary.

Who are other famous stutterers?

There’s tons of them. You’d be shocked. Winston Churchill stammered. In the movie, they allude to the fact that he had a speech problem of his own. There are clips online where he does stutter in places. Marilyn Monroe, James Earl Jones, Joe Biden are biggies. (An extensive list is available here.)

What message did you take away from The King’s Speech?

I thought the movie was really about courage. It was an inspiration to see George be so courageous under such circumstances. But the circumstances for a king are the same circumstances a second grader has to face when he has to read aloud in class, the same kind of pressure. It’s about how do you have courage in the face of fear. It’s not that courage is having no fear. It’s having fear and acting anyway.

What the movie will do is help the public understand that people who stutter are just like you and me in every other way. For people who stutter, it may give them the confidence that they can unleash the king in them, so to speak, to be who you are and live a fulfilled life, to do what you want, even when the circumstances make it look like it’s impossible.

To learn more or find help, visit the Stuttering Foundation and Friends Who Stutter, which focuses on children.

Caleb Daniloff can be reached at cdanilof@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.