The Porous Frontier

CAS prof: Voyager indicates radiation could penetrate our solar system

If you’ve dreamed of volunteering for that manned flight to Mars that NASA is planning, better pack a damn good hazmat suit. New research by Merav Opher, a College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of astronomy, and others suggests that the border of our solar system may not be the radiation-deflecting shield scientists once thought it was.

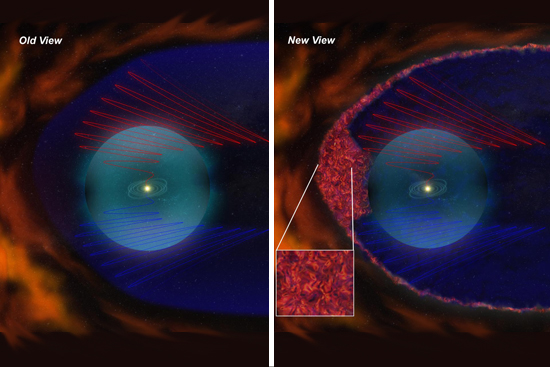

Rather, data transmitted from the Voyager probes, launched when Jimmy Carter was president, indicate that the heliosheath, the region between our solar system and interstellar space, is a porous brew of massive magnetic “bubbles.” Cosmic rays may be able to penetrate this boundary, the researchers say.

While rays pose no threat to Earth dwellers, who are protected by our planet’s atmosphere, astronauts rocketing to Mars need to beware of radiation leaking in from outside our solar system, Opher recently told National Geographic. Cosmic rays can damage astronauts’ DNA and immune systems.

The findings, announced last month at a NASA press conference and in a June Astrophysical Journal paper, would upend our understanding of the solar system’s outer rim 10 billion miles away if confirmed by further study. For now, she says, “These findings are very important in the sense that we are learning about our home,” the region of the sun’s influence. “Related to a manned trip to Mars, it also has implications. Astronauts in long exposures can be affected by radiation coming from galactic cosmic rays.”

Opher says that the new theory explains the data coming from the Voyagers, but the information from those 34-year-old spacecrafts needs to be double-checked by newer, “more sensitive instruments” in the future. For now, the bubbles theory is based on a computer model that relies on the Voyager data.

The two probes have documented wrenching ups and downs in the amount of electrons in the heliosheath. The roller-coaster readings would comport with the existence of magnetic bubbles, the computer model indicated. The vast bubbles—100 million miles long and sausage-shaped—trap particles like electrons. As the probes enter a bubble, electron readings spike, then drop when the probes leave the bubble.

The bubbles may temporarily trap cosmic rays, but it’s possible the rays may escape and enter our solar system, Opher and her colleagues say.

The heliosheath lies at the edge of the magnetic field thrown across the solar system by the sun. The researchers speculate that the rotation of the sun creates folds in the field that break into bubbles in the heliosheath. That region of space, Opher told PBS, is like “a really agitated Jacuzzzi.”

As a guest investigator for NASA (she once worked at a NASA-affiliated center), Opher receives financial support from the space agency for her research. The daughter of an astrophysicist, she has long been intrigued by space, although at one point, she says, she did “seriously consider being a film director.” She settled on science after a college professor “showed me how physics can be poetic, and this hooked me. I realized that physics can be as exciting as movies and opera!”

Rich Barlow can be reached at barlowr@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.