The Science of Anthropology

BU anthropologists on whether the field is a science

The decision by the American Anthropological Association last fall to delete three references to “science” from its long-range plan drew volcanic eruptions from some outraged anthropologists. According to a New York Times report, the plan, which had said the AAA aspired “to advance anthropology as the science that studies humankind in all its aspects,” now says its goal is “to advance public understanding of humankind in all its aspects.”

Critics of the change charge that cultural anthropologists—who study such topics as race, ethnicity, and gender—disdain science and favor political advocacy for human rights and indigenous peoples. (Anthropological fields rooted in science include archaeology, the study of nonhuman primates, the study of fossils, and some cultural anthropology.) The AAA board issued a statement saying the Times and other media have “blown out of proportion” the wording change. It simultaneously released a document, “What is Anthropology?” to clarify its position. That document says anthropology draws on “the social and biological sciences as well as the humanities and physical sciences.”

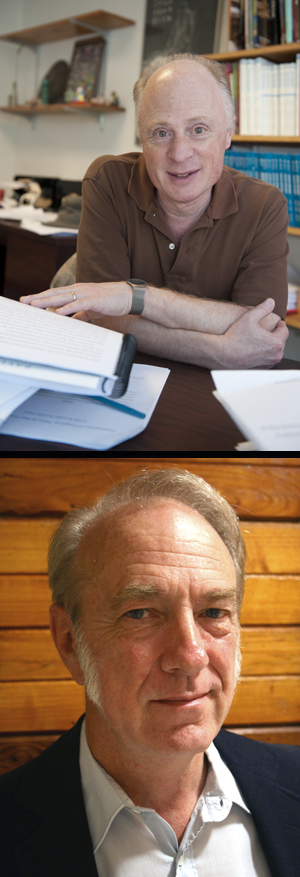

BU Today sat down with two University anthropologists to parse the debate. Robert Weller chairs the College of Arts & Sciences anthropology department and falls into the cultural anthropology camp, specializing in the study of Chinese and Taiwanese religion and religious authority. Biological anthropologist Matt Cartmill, a CAS professor and director of graduate studies, hails from the science-rooted camp, studying human evolution. The two agree that their department hasn’t been torn by war between science-based and cultural anthropologists, as has happened elsewhere.

BU Today: Do you agree with the decision to delete the word “science” from the plan?

Weller: I wouldn’t have done it. I don’t see what is gained. A lot rides on what we call “science.” If we mean scientific method—controlled experiments in laboratories with disprovable hypotheses and reproduceable results—lots of us don’t do that. I don’t do that. But there’s long been an anthropological line: let’s take the term in its German sense, which just means trying to put order on knowledge. I’m totally comfortable with that—I claim science.

But I don’t read the change as a real attack on the scientists, either. The critique of science isn’t from the majority of social and cultural anthropology, but it’s been a vocal piece at certain universities, of which ours is not one. I have no problem with the rewording, either, and I would say zero people in this department have a problem, one way or the other.

Cartmill: I see no reason why it should have been deleted. I think there are all sorts of things that are worthwhile for people to do that aren’t science. But I don’t think there’s anything wrong with doing science. There are anthropologists who describe science as “cognitive colonialism.” I am outraged by people calling me a cognitive colonialist.

But I’m not outraged by people saying that they’re not scientists. Science is theorized, repeatable experience—I can go and check you, see if what you said is true. It is an extremely useful formula for getting at what’s going on in terms of nature. It’s less useful for talking about human motivations, desires, ambitions, psychology. I am also sensitive that there are people who treat science as though it were something handed down from Mount Sinai, authoritative. Science does not recognize the existence of authority; you’re always obliged to say, “Check me out.”

I have done things that weren’t scientific. I wrote a book that was an intellectual history of hunting.

Weller: We’re all about humanity, what it means to be human, how we got to be human. I don’t like reducing everything to a gene.

Cartmill: Me, either.

Weller: On the other hand, there’s nothing we do where genes aren’t involved. This conversation has a lot of genetic components to it.

Cartmill: Which is why you’re not having this conversation with a moose.

The AAA said the media coverage of this debate was “blown out of proportion.” Do you agree?

Cartmill: I don’t think it was blown out of proportion. I think this is a real source of pain and irritation. I know it is on the biological anthropology side.

Weller: I think it’s overblown. I think there’s a very vocal minority on both ends. I don’t think that’s a huge number of people.

Cartmill: We never took a poll, but when this subject comes up at meetings of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, voices are raised.

Some fret that deleting the word “science” risks undermining the public’s perception of anthropology.

Cartmill: Sure, I worry about that. But like almost any community definable by almost any principle, it’s got warring political factions. This is not unique to anthropology.

Weller: I don’t think this changes the public perception. I’d be more concerned if it undermined funding from the National Science Foundation. The NSF, at least so far, seems unconcerned.

Is this a minor flare that’s going to die down?

Weller: I wouldn’t be surprised if it came up at the next AAA meeting in November. Until those events, nothing much is going to happen.

Cartmill: People like me are going to go on, endlessly, being irritated by people saying that science is a device for getting control over the poor and downtrodden of the Earth, because I haven’t got any of that control.

Rich Barlow can be reached at barlowr@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.