The Second Coming and Other Utopias

CAS historian on millennialism

Jesus will return to Earth just in time for BU’s Commencement. So says Christian radio executive Harold Camping, who predicts that the Rapture (the midair meeting of Jesus and “saved” Christians) will start May 21, which happens to be the day before graduates gather on Nickerson Field. The forecast is just the latest development in Americans’ long-running fascination with millennialism, the belief that Jesus or some other messiah will at some future point inaugurate a kingdom of peace and justice on Earth, followed by the end of the world.

The Pilgrims embraced the goal of a purified Christian church that would usher in God’s kingdom in the New World. More recently, millennialism infused the Y2K fears of over a decade ago, which forsaw worldwide computer chaos with the date change from 1999 to 2000, and the Heaven’s Gate cult, whose members killed themselves in 1997, believing the Comet Hale-Bopp signaled the arrival of a spacecraft ferrying them to heaven.

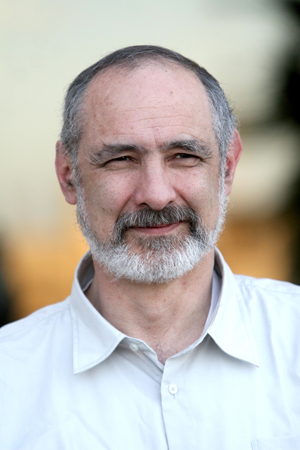

Richard Landes’ forthcoming book, Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience, due this summer from Oxford University Press, surveys millennial beliefs from antiquity to today. Landes, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of history and head of BU’s Center for Millennial Studies, is an expert on millennialism and apocalypticism, the belief that either the millennial kingdom or the end of time is imminent. These impulses don’t belong just to the religious, he says; believers from secular revolutionaries to political ideologues hoping for a perfection of earthly life hold to a kind of millennial thinking.

Landes is spending the semester in Germany as part of the International Consortium for Research in the Humanities, a scholarly project researching East Asian notions of predicting fate and destiny. BU Today spoke with him about why a belief that has been proven wrong so often remains so potent today.

BU Today: Is millennial thinking confined to Christianity?

Landes: Absolutely not. I have 10 examples in the book. None of them are Christian or Jewish. I do stuff on tribal societies in South Africa and Papua New Guinea, the Chinese millennial movement at the time of the American Civil War, the French Revolution, Nazism, communism. My last chapter is global jihad.

In Islam, Jesus actually does have an apocalyptic role, which Mohammad does not. He’s got various roles to play according to the given scenario, but there is a place for Jesus to come back and participate in the end-time process.

How prevalent is millennial thinking today?

Let’s throw seculars in. I would say Western thought is fundamentally millennial. It’s all about perfecting the world, making the world a radically better place. Science is a form. When you read the stuff from artificial intelligence people and artificial life people, they’re thinking in messianic terms: “This is the biggest change in human history.” I suspect there’s probably a significant rollover of people who were afraid of Y2K into global warming fears, because it’s another technology-induced, predicted apocalypse.

Christians who believe in the Rapture include Pat Robertson, James Hagee. After Y2K, they went into imaginative mode. The point of the Left Behind series, the best-selling novels about the Rapture, is to whet your appetite for what’s to come and give you an imaginative substitute for what hasn’t come. In apocalyptic belief, wrong doesn’t mean that people go, “Oh, I was wrong.” You stop announcing that it’s imminent. You punt and get ready for the next round. The guys who did 9/11 were steeped in Islamic apocalyptic belief. Global jihad is driven by it, Hamas is driven by it, Hezbollah is driven by it.

We should care about apocalyptic dynamics because wrong does not mean inconsequential. We don’t have a clue about how to deal with jihad because we don’t understand what motivates it: the conquest of mankind, which will inaugurate a period of peace and justice and God’s rule on Earth through Sharia, or Islamic law. The guy who’s about to blow himself up in the London subway probably wouldn’t know about this stuff, but the people who set it in motion are believers.

It’s not like we can talk them out of this.

We think we can. A significant number of pundits say Israel should talk to Hamas. They wouldn’t ask America to talk to al-Qaeda, but look at what we’re doing with the Taliban: U.S.-sanctioned talks between the Taliban and the U.S.-allied Afghanistan government. We want to believe they’re rational, because we don’t know what to do with irrational people. Remember, when you’re thinking about the Taliban, you’re thinking about a religious movement that when it had power was throwing acid in the faces of women who didn’t wear veils.

Is there reason for concern that Christian millennial movements could turn to violence?

Christian millennialists believe God will have to destroy most of mankind for the millennial kingdom to come, but they don’t think it’s their job. I can live with people who say, “God’s going to zap you.” I have more difficulty living with people who say, “God wants me to zap you.” But the likelihood of American Christians flipping to violent millennialism will increase the more powerful cataclysmic apocalypticism becomes in the Muslim world.

Most people think of millennialism as the history of nonsense: these people have all been wrong. I think there’s a real problem there. I think it should be a major field of study. The most destructive force in human history is active, cataclysmic, apocalyptic ideas.

Rich Barlow can be reached at barlowr@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.