The World, Post 9/11

BU faculty and staff on what’s changed in decade since

World Trade Center photo by New York City photographer Bill Biggart, who died while shooting the events of September 11, 2001. Photos below by Vernon Doucette, Cydney Scott, and Kalman Zabarsky

This weekend, the United States will commemorate the 10-year anniversary of 9/11 with memorial services, concerts, and readings across the country. On that day in 2001, 2,753 people lost their lives at Ground Zero in New York City, at the Pentagon in Washington D.C., and in a field near Shanksville, Pa., the result of four coordinated suicide attacks by 19 al-Qaeda terrorists.

As the nation prepares to mourn and remember those who died, BU Today asked several University faculty and staff members to talk about how the events of that day changed us as individuals and as a country.

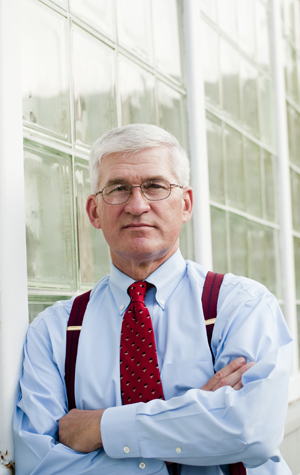

Andrew Bacevich

College of Arts & Sciences professor of international relations, West Point graduate, and retired U.S. Army colonel, author of Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War. His son, 1st Lt. Andrew Bacevich, Jr. (CGS’01, COM’03), was killed in a bomb blast in Iraq in 2007.

The post-9/11 decade has transformed American expectations about war. Prior to 9/11, influenced in particular by Operation Desert Storm back in 1991, Americans—civilian and military alike—had come to believe that U.S. forces had mastered the art of war. On the battlefield, we called the tune; others danced. So we thought.

By extension, any conflict involving U.S. forces was all but guaranteed to be settled in short order, on favorable terms. Simply put, victory was a sure thing, gained quickly and cheaply and cleanly.

The events of the past 10 years have demolished such expectations. Decision has proven elusive. The wars that we have chosen to wage have turned out to be long, costly, and dirty. Today Americans, civilian and military alike, have pretty much given up on the very concept of victory. In Iraq and Afghanistan, we will settle for turning the problem over to local forces. The new standard of success is to disengage without acute embarrassment.

Note, however, that even if Americans have given up on victory, they have not given up on war. Instead, war has become the new normalcy. The American people, themselves largely insulated from the effects of war, accept war as a quasi-permanent condition. That’s what the past decade has produced.

Thomas Robbins

BU police chief and executive director of public safety; was a Massachusetts State Police captain, serving as chief of staff to the superintendent, on September 11, 2001, and later director of aviation security for Massport.

Nearly every generation throughout history has suffered a tragic, man-made event that has profoundly affected their lives, changing them forever. The assassinations of Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59), and President John F. Kennedy are three such events that shocked the conscience of a nation. Immediately after the 9/11 attacks, I was assigned to Logan Airport as the director of aviation security for Massport and concurrently as the newly promoted major in charge of troopers assigned the duties of policing the airport. On December 22 of that first year, Richard Reid (the “shoe bomber”) paid a visit to Logan, a stark reminder that the threat of terrorism was to be with us for a long, long time.

In a short time period after the attacks, there were many systemic changes made at the federal level, including the creation of a new Department of Homeland Security, screeners at airports, expanded surveillance powers, and an overhaul of the intelligence community. The greatest change for state and local police was a shift in posture from responding to crimes that have already occurred to identifying potential crimes before they occur. This shift put state and local police in the position of gathering intelligence information and investigating potential terrorist activities within our borders. Another major change was upgrading our capacity for critical incident management, including interoperability of communications and unified command structures for multi-agency responses.

On an emotional and personal level, the greatest change was a sudden awareness that domestic law enforcement was vulnerable and not immune to the senseless violence associated with political and religious extremism that has and continues to plague much of the rest of the world. The 9/11 generation is much wiser now, but also a bit more cynical about the possibility of seeing, in our lifetime and our children’s lifetime, true world peace.

Neta Crawford

CAS professor of political science and coauthor of the recently released Costs of War study.

The 9/11 attacks understandably frightened many in the United States, especially traumatizing those who lived in Washington, D.C., and New York. Most fear reactions fade.

Fear may also be institutionalized in the body politic: new practices are specified, becoming routine. The once-strange or new becomes the normal.

The institutionalization of fear in the United States post 9/11 can be observed in hypervigilance at home, increased military spending, and a more aggressive military policy.

Within a few weeks of the 9/11 attacks, Congress enacted the U.S.A. Patriot Act, which gave unprecedented powers to the U.S. government to monitor its citizens and their communications. It authorized the indefinite detention, without trial, of immigrants suspected of ties to terrorist organizations.

The annual budget for the Pentagon was just over $400 billion in 2001; 10 years later, it is about $700 billion. Total Pentagon spending on the wars so far is $1.2 trillion. Military spending in what is called the nonwar base budget has also grown. When war spending decreases, base budget increases will likely remain.

The annual budget for the Pentagon was just over $400 billion in 2001; 10 years later, it is about $700 billion.

Past wars were generally paid for by taxes or war bonds, but most of the money for the current wars was borrowed, increasing the federal deficit and debt. The United States has already paid about $185 billion in interest on Pentagon war spending. Tens of thousands of veterans who have returned from the wars with injuries will need increased medical and disability care over the next 40 years. This institutionalized budgetary burden—interest on war-related debt and payments for veterans’ medical and disability needs—will cost perhaps another $2 trillion over the next several decades.

War has become so normal that escalation such as the remotely piloted drone strikes in Pakistan and Yemen, for example, which have killed about 2,000 people, many of them civilians, have hardly been noticed by the general public, nor closely monitored by the U.S. Congress.

Kecia Ali

CAS associate professor of religion and member of the Institute for the Study of Muslim Societies and Civilizations executive committee.

Before 9/11, one could spend an entire career as a scholar of Islam without talking to a reporter. Now, outreach to the press and the general public is a critical component of the job. Still, despite efforts to make high-caliber scholarship accessible, accurate information and thoughtful analysis has had frighteningly little impact on widespread ideas about Islam and Muslims. Some misconceptions (e.g., Obama is a Muslim; Muslims want to impose sharia in America) are the product of lavishly funded misinformation campaigns, which have led more Americans (49 percent), according to a Washington Post–ABC News poll) to view Islam negatively in September 2010 than in 2002 (39 percent). Scholars of Islam have to contend with these new errors as well as the older assumption that anything involving Muslims—from women’s participation in Egypt’s recent uprising to mommy-and-me playgroups for Indian immigrant families—can be explained in religious terms. This focus on religious motives is continually reinforced through media framing of a conflict between the West and Islam, with fundamentalism at its center. Broader economic and social realities are too often ignored.

The civilian death toll in Iraq is perhaps 200 times as significant a proportion of the population as the 9/11 victims were to the United States.

The 9/11 attacks shook the basic presumption of security that middle-class Americans had taken for granted, but that many outside our country and some inside it, such as the poor who were overwhelmingly Katrina’s victims six years ago, did not then and do not now enjoy. The war on terror, with drone attacks in Pakistan and the invasion of Iraq, has exacerbated global violence and instability. The direct civilian death toll in Iraq since 2003 is, taking lowball estimates, perhaps 200 times as significant a proportion of the population as the 9/11 victims were to the United States (only a fraction of these deaths are directly due to United States/coalition forces—see iraqbodycount.org). This bigger picture is impossible to explore in a sound bite, difficult in an op-ed. Good journalism is a start, but real change in people’s thinking must come through sustained engagement with facts and ideas—which is, of course, what universities are for.

Jack Beermann

School of Law professor and Harry Elwood Warren Scholar, teaching administrative law, civil rights litigation, and local government law.

The world has undergone myriad changes since 9/11, many for the worse. The single most significant change to me has been that we seem to live in a constant state of anxiety, whether it is about terrorism, global warming, the economy, or the federal budget deficit. My four children, all 18 years old and younger, have grown up in a country at war all the time. September 11 has contributed to a loss of privacy and freedom at home and a sense of helplessness about our role in the world. Incredibly, instead of asking people to sacrifice for the common good, we have reduced taxes on the wealthiest among us (apparently without saving or creating jobs, which is what we were told the tax cuts would do) while pushing the costs of two major wars and massive economic stimulus off on our children and grandchildren. Our politics seems more fractured than ever, perhaps due to post-9/11 anxiety. China is rising, temperatures are rising, and the seas are rising, while the United States seems to be sliding toward status as another former great world power. Good jobs have moved overseas or disappeared altogether. There are glimmers of hope: racial progress as represented by the election of President Barack Obama and hope for democracy, exemplified by popular uprisings throughout the Middle East. But we seem farther than ever from the peace, love, and end of poverty that were the promises of the 1960s when I grew up.

Hillel Levine

CAS professor of religion and president of the International Center for Conciliation.

Which 9/11 will you mourn? There are, indeed, many.

For each we experienced fear and anger, shame and self-reproach, blame and vindictiveness. We seek hope and reform. We crave protection when we put up with the indignities of airport inspections, but what we really acknowledge as gone are the days when we could sit on a plane without imagining neighbors preparing to blow us out of the sky. We long for the renewal of public trust.

What is the quality of public life in responding to more recent catastrophes, like the financial melt down of 2008? What have our government, corporate, education, and religious leaders learned from horrible 9/11 failures that could have prevented sequels? The intelligence agencies with their huge resources that indulged in bureaucratic rivalries, the regulatory agencies that did not regulate, the security workers who were neither adequately trained nor equipped, but in their devotion resorted to self-sacrificial risks rather than well-thought-out strategies, the corporate world that competes for market share and short-term profits rather than reputation and service to the American people—where do we go from here?

The 9/11 and subsequent catastrophes for which I will mourn involve the failure of political and moral leadership. Our enemies are not the hundreds of millions of Muslims, many of them now publicly protesting the inadequacies of their leaders. They share with us the need for global prevention.

How do we, Americans on the left or the right, delude ourselves into believing that globalism or localism will promote peace and prosperity for Americans or anyone else? Will promoting predatory rather than well-regulated entrepreneurial capitalism restore our public trust at home and our reputation abroad?

This post-9/11 decade has unleashed a corporate neocolonialism disguised as globalism, unregulated in outsourcing our neighbors’ jobs and allowing deceptive bankers to confiscate their homes, both travesties backed by federal subsidies. Can 9/11, an unprecedented assault on American civilization, catalyze a force of renewal or will it cast us all into a hopeless whirlpool of despair and irreversible decline? We well may know the answer considerably before that 20th anniversary.

Richard Cornell

College of Fine Arts professor of music and composition and School of Music associate director; his composition Falling from a Height, Holding Hands was inspired by a poem about 9/11.

The attacks on September 11, 2001, were felt widely and profoundly, and the entire world was focused on this tragedy. The images still haunt us, and we can never forget the day and those who died. We cannot forget the sacrifices, the acts of courage, the inspiring resilience of so many on that day, and of those who served us since and those who serve today. So many have paid with their lives.

For a few days that fall there was a hushed quality to daily life as we grieved. We recognized that we were one people united by the loss and that we relied on each other. We realized we were not Americans only and that people far and wide felt sympathy, loss, and common cause. As we remember this event and those lost 10 years on, we need also to recall what we learned closer to that day. It is important that we study the complexities, the details, and the history and that we don’t oversimplify or generalize the events to support facile conclusions. We cannot let it only yield 10 years of asymmetrical war.

Shahla Haeri

CAS associate professor of anthropology and author of No Shame for the Sun: Lives of Professional Pakistani Women; has written extensively on religion, law, and gender dynamics in the Muslim world.

By sheer coincidence I was teaching Sophocles’ Antigone in my course on conflict resolution on that fateful September day that changed the world—alas not for the better, at least not so far in America. A major theme in this undying tragedy, written some 400 years before Christ, has to do with the role of a leader at times of crises and chaos. Tragedy becomes inevitable in the absence of a leader’s transcendental vision and wisdom, and his inability—or unwillingness—to negotiate intractable conflicts. The catastrophe that struck America provoked heartfelt sympathy for the Americans and universal condemnation for the perpetrators. But the global goodwill dissipated just as quickly as it had been spontaneously formed when our leaders lost sight of their initial moral objective and diverted their attention from reconstructing Afghanistan to invading Iraq. As the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq dragged on, our leaders dug their heels deeper in the quagmire. Lost in the fog of war, political vigilantism, isolationism, and ideological intolerance replaced American democratic idealism, and corporate greed rampaged our economy. While the election of an African American president revived many Americans’ hope of moving forward, surprisingly, it awakened dormant racism among some, inflamed ideological divisions and social cynicism. Ironically, President Obama’s election and leadership have inspired millions of Arab youth to revolt against their own despotic leaders in hopes of institutionalizing democratic principles. A good and wise leader inspires globally, if not always locally.

Joseph Wippl

CAS professor of international relations and former Central Intelligence Agency officer.

Did 9/11 change us or was the event of 9/11 used to change us? Within a few days after the attack, I found myself as an American official at a vigil for the 9/11 victims in Berlin, Germany, with the Cardinal Archbishop of Berlin, Georg Sterzinsky. The cardinal said the United States had the right to bring the perpetrators to justice through violence, but should not overreact—that is, should only respond in a way commensurate with the attack itself. At first, this occurred with the invasion of Afghanistan, toppling the Taliban government and targeting those planners and implementers of the 9/11 attacks. Then, very rapidly, the United States mutated from a country or nation into a homeland under existential threat. Iraq was conquered, and along with Afghanistan, never-ending nation-building ensued. National and international laws were ignored in order to “save (never identified) American lives.” As the aggrieved party, we now took off the gloves. While lives were lost, physically and mentally wounded lives remain, as do debts borrowed to fund the wars. Al-Qaeda and the United States now have one thing in common: they are both substantially weaker 10 years after 9/11.

Margaret Ross

Director of Behavioral Medicine at Student Health Services.

Ten years ago, the people now entering college were eight years old, in the third grade. They were playing video games, learning arithmetic, eating macaroni and cheese. George Bush the Younger was doing his impression of being a president. Cell phones were not nearly universal in the United States, not everyone had a computer or email, and there was still such a thing as playing outside in the neighborhood. There was the belief that if you worked hard, you could do well and get ahead. People were not in constant contact on electronic devices, and Facebook did not exist. On 9/11, many landlines jammed as people tried desperately to get information, and especially, confirmation that those they loved were safe.

In college-age people today, there is much less optimism about the future, the reasons for which are not too hard to understand. The economy, after plummeting in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, rebounded reasonably quickly, and some people began to feel hope that things would work out. Then, 2008 and the mortgage crisis happened, Lehman Brothers imploded, and unemployment figures became the headlines. The intensely bipartisan nature of the federal government is paralyzing our leaders, and it is hard to feel optimistic about the future, especially for people growing up now and contemplating what they will do when they finish college.

What will allow us to rebuild after 9/11? How to address the collective anxiety, mistrust, lack of optimism?

Will it help to build 9/11 memorials in a world with no jobs for students graduating with nothing but debt and student loans? How do we deal with the bitterness people feel, and the hopelessness about the future? What about the endemic racism and anti-immigrant sentiments that simmer beneath the surface in our country, and sometimes erupt in violence? What about the ever-widening chasm between the super-rich and the 99.999 percent of people who struggle each day to find the barest essentials necessary for survival—not to mention human dignity? And what of the government that protects these super-rich and leaves the common man to fend for himself, lose his home, lose his job?

What ideals, ethical principles, and visions do our young people have today, and how has the experience of growing up in America been changed by 9/11? How to replace aspirations for wealth and material goods with goals to repair the world, to make it a better place? How to replace disillusionment with hope and optimism?

I know I’m asking many questions and furnishing few answers, but I do believe that we have faced challenges in this country even greater than those posed by the decade post-9/11, and those difficult times gave rise to what has been known as the Greatest Generation. And, to be honest, my hope comes from thinking that there are voices in the current generation of young people, committed to getting through these years, who will bring the world back into balance.

I have heard many inspiring stories in the years I’ve been at BU, and from the people I meet every day, I draw great hope. So many academic and administrative staff members serve the students with relentless energy, commitment, thoughtfulness, expertise, and dedication. And the students—so many extraordinary young folks who are spending every spare moment working with the programs for the Community Service Center or working with religious groups on campus or working with Boston public school students to educate them about health-related issues or participating in one of the hundreds of activities dedicated to helping others. This is how I know we will emerge from this difficult and challenging time with renewed strength and optimism. It is because of these people, at BU and at so many universities and nonprofit organizations here in the United States and overseas, who will bring us to a new era of renewal and optimism. It takes hard work, strong leaders, sacrifice, and commitment, but it has been done before, and it can be done again. Let me rephrase: we, young and old, working together, can do it again.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.