Seeing Double: Aging Study Focuses on Unique Group

BU psychologists study Vietnam vets who are also twins

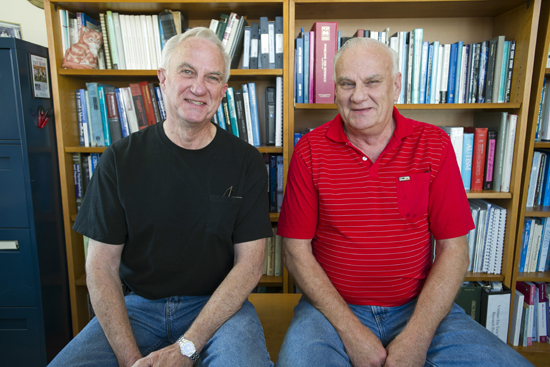

Twins Winston Harris (left), of Washington state, and Winfred Harris, of Texas, are participants in the Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging, being conducted by BU psychologists. Photos by Cydney Scott

Why do some people grow old gracefully, with intellect intact and few illnesses, and others decline rapidly? Successful aging is undoubtedly the result of both genes and environment, but how are the two intertwined?

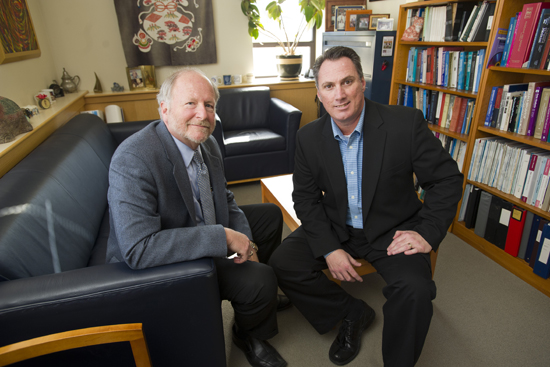

A team of Boston University scientists, led by Michael Lyons, a College of Arts & Sciences professor and chair of the psychology department, and Michael Grant, a CAS research assistant professor of psychology, is answering these questions by studying an unusual group of subjects: 1,237 men who served in the military during the Vietnam War and who also are twins. The study, called the Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging, or VETSA, is noteworthy for both its impressive number of subjects and its special focus on cognitive aging. Funded by grants totaling more than $9 million from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), VETSA is unique among aging studies because the scientists started observing the veterans at midlife, before many age-related declines had begun.

Why twins? And why veterans? It turns out that both factors provide valuable data to scientists. “There is a theory that health will be more influenced by genetics as people age,” says Lyons. Scientists have long suspected that aging is less an accumulation of environmental factors than a triggering of certain genes. Studying twins, both genetically identical and fraternal, allows researchers to test this hypothesis. So far, it appears that genes do play a bigger role for many characteristics, he says, “but we’ll see what happens as we follow them over time.”

Veterans are a particularly useful group to study because the military records each soldier’s height, weight, and blood pressure at the time of induction, enabling the scientists to trace these measurements back several decades. Another rare feature of studying veterans is cognitive data, in the form of the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), which each man took upon entering the military. The AFQT contains 100 questions testing vocabulary, arithmetic, knowledge of tools and mechanical equipment, and spatial visualization. The military no longer uses this exact version of the test, first administered in the 1960s, so the VETSA team needed special permission from the Pentagon to use it. By giving the test now and comparing the results to the original, the researchers collect valuable data on cognitive aging over several decades.

Studying this particular group of veterans does have some limitations, the biggest being that all the test subjects are men. Because the percentage of women in the military during the Vietnam War was small, the chance of finding female twins among them was less than .01 percent. Another limitation is that most of the men in the sample are Caucasian, although all ethnic and racial groups are represented. Finally, and most obvious, there is also the question of whether combat—an experience not shared by the general public—influences veterans dramatically as they age. And in fact, the first publication based on VETSA data found that twins who had actually gone to Vietnam attained slightly lower education over their lifetimes than their siblings who had not seen combat.

Despite these limitations, Lyons and Grant say that their study sample offers valuable parallels to the general population. They note that only about one-third of the men in VETSA actually deployed to Vietnam, and that in most other respects—from socioeconomic status to nicotine dependence—they are remarkably similar to Americans in general. “When I see these guys in the lab, they look a lot like me,” says Lyons, who is a Vietnam veteran.

The BU researchers are collaborating with a team at the University of California, San Diego, headed by William Kremen (GRS’90). The twins choose either Boston or San Diego for testing, and for brothers who live far apart, the tests offer a chance for reunion.

Not that testing is a picnic. Each twin undergoes a rigorous seven-hour day of testing, beginning at 8 am. Researchers give each man a full physical workup, measuring height, weight, blood pressure, vision, hearing, grip strength, and other factors. The men fill out questionnaires to determine the quality of their social relationships, their alcohol consumption, and their overall well-being, among other things. Researchers draw blood, test strength, and run the men through 12 cognitive exams, including memory puzzles and the AFQT. Each man provides a genetic sample and some also volunteer for an MRI of their brain.

And, somewhat surprisingly, five years later they come back for more. “They love VETSA,” Lyons says with a laugh. Each man receives a small stipend and travel expenses, but Grant—himself an identical twin—suggests another reason for the research subjects’ enthusiasm. “Twins find themselves unique anyway,” he says, “and they like the fact that they are contributing to important research.” He notes that the researchers inform subjects if they detect any serious health problems.

For the first VETSA, which ran from 2002 to 2007, the scientists needed about four years to collect data on all 1,237 men. Currently, they are about halfway through the second round of testing, called VETSA 2, which began in 2008 and will run until 2013. “This is going to be a great wealth of data,” says Grant. “It already is.” So far, researchers have produced more than 50 scientific papers from the data, and some of the findings are surprising.

One of the biggest discoveries so far involves apolipoprotein E (apoE), a gene important for repairing damaged neurons. People with a certain version of the gene, called C4, are more likely to get Alzheimer’s disease and also have more difficulty recovering from stroke or other brain trauma. Lyons, Grant, and their colleagues wondered if people with the C4 version of apoE would be more susceptible to psychological trauma as well. It turns out that they are. In research presented at the World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics in 2010, they found that people with the C4 version of the gene had an increased risk of post-traumatic stress disorder if they experienced high levels of combat exposure. This was the first evidence that a gene that makes people more vulnerable to physical brain injury also increases vulnerability to psychological trauma.

Another important finding, which Grant will present at the 2011 Gerontological Society of America annual meeting later this month, involves erectile dysfunction, or ED. ED has long been associated with many health problems, among them diabetes, high blood pressure, and depression. With data from the twins, Grant was able to determine that ED is strongly hereditary, with more than half the variation among individuals due to genetic factors. Along with psychology graduate student Caitlin Moore (GRS’15), Grant is continuing to pursue research in this area. They suspect that ED may also prove to be one of the first signs of cardiovascular disease and an early indicator of cognitive decline.

Lyons, Grant, and their colleagues at BU and UCSD have collected about half the data for VETSA 2. They hope to secure additional funding from the NIA so they can continue the study. The longer the scientists can follow these men, the more they’ll learn about the links among genes, environment, and successful aging, knowledge that will benefit us all.

Barbara Moran (COM’96) is a science writer in Brookline, Mass. She can be reached through her website WrittenByBarbaraMoran.com.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.