Why Poetry Should Be Spoken

Robert Pinsky reads from his new Selected Poems tonight

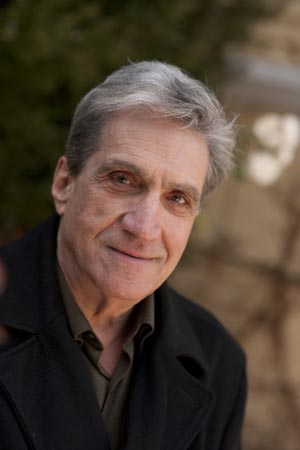

Over a distinguished career spanning more than four decades, Robert Pinsky has written hundreds of poems and amassed numerous honors.

Pinsky, a three time U.S. poet laureate and a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English, has won a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship as well as two of poetry’s most distinguished honors: the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America and the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize. He has also been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

But Pinsky is known as much for his advocacy of poetry as he is for his poetry. As poet laureate from 1997 to 2000, he created the Favorite Poem Project, which encouraged Americans of all ages, backgrounds, and geographical areas to share their favorite poems. As poetry editor of the online magazine Slate and in appearances on such popular television programs as The Simpsons and The Colbert Report, he has championed the importance of poetry in American culture. He has even applied his talents to opera, writing the libretto for Tod Machover’s Death and the Powers, which premiered in the United States this month at Boston’s Cutler Majestic Theatre. One critic, reviewing his 2007 collection Gulf Music for the New York Times, hailed him as “the civic poet.”

Tonight, Pinsky will read from his newest book, Selected Poems (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, April 2011), at the Photonics Center at 7:30 p.m. His eighth volume of poetry, Selected Poems contains no new poems—rather it’s a kind of summing up of his career, an opportunity to distill a lifetime’s work into one volume. That got us wondering how, in a book like this, a poet as prolific as Pinsky goes about selecting what to include and what to leave out. And so we asked him.

BU Today: How did you choose what to include in Selected Poems?

Pinsky: I have great friends, and as with many things to do with writing, their advice is important—and, also as with other things, including writing itself, you are ultimately on your own. It seemed important to represent each book or phase of my career, made a little more difficult by long poems. My first book, Sadness and Happiness, contains the long-ish title poem and the extended “An Essay on Psychiatrists.” The second book, An Explanation of America, is mostly one poem. For this Selected, I include all the poems from the first volume and brief excerpts from the essay and second volume.

Is there anything that thematically connects these poems?

One way or another, everything I’ve ever written has to do with the world of made and made-up things I was born into: religions, movies, people, customs, laws, foods, jokes, tragedies, wars, stupidities, technologies, a town, a family, truths, lies, words, gadgets, cheeses…and so forth. To put it differently, no matter where I start, I seem to end up thinking about culture, especially American culture, and my place in it.

Was there anything that surprised you in sifting through a lifetime’s work for this new book?

The consistency surprised me, as it often does. I could add a sort of circular, rather than linear, sense of time. Another surprise was detecting, often in a submerged way, the Hebrew school of my childhood—not just beliefs or a worldview, but the feel of it, and formal matters like learning by rote a language with characters mainly for consonants, with vowels as subscripts. The chanting.

You chose not to include any new poems. Why?

My friend, editor, and publisher Jonathan Galassi had a strong opinion that a “New and Selected” is an awkward combination of things. He argued for the elegance of publishing this book, and then, in a couple of years, a new book. As soon as Jon said that, I was convinced, and his opinion seemed echoed by something in me that wanted a pure summing-up at this point in my life.

In Selected Poems, the acts of both remembering and forgetting are frequent leitmotifs. What intrigues you about the subject?

Forgetting becomes an increasingly important subject as you get older, not because of memory failure, so much, as because you have seen many things rise and then fade, in the world at large and in your own experience. Some are dear, some are trivial. I feel increasingly pious about my cultural ancestors and my literal ancestors: great-grandparents and their parents, important teachers and their teachers—all the people, mostly anonymous—who made this world and me. To think about them, and to think about the limits of my own life, is to think about forgetting and, yes, about remembering, too.

Is it true that being a jazz musician during high school inspired you to become a poet?

Music was the only thing I did all right at in high school. It was the one competence that got me through rather difficult years. The attempt to be an artist (a pretty feeble attempt) kept my mind alive. Maybe it kept me alive!

What inspires you to sit down and write a poem?

Great works of art inspire me: it’s not unlike what makes a three-year-old at a wedding begin to dance when the band starts up and the grown-ups begin to dance. So, Emily Dickinson and Ben Jonson and Walt Whitman and John Keats inspire me. Poems like Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale” or Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for death” or Jonson’s “Let it not your wonder move” give me a certain feeling, and I start to want to try to create that feeling.

You’ve been called America’s “civic poet.” Is that an accurate description?

I don’t know. It does seem that I am more interested in writing about streets and towns and such than some people are. Maybe it comes more naturally to me because I grew up as a small-town provincial. Francis Fergusson’s description of the ancient Greek theater in The Idea of a Theatre—“civic” I guess—was formative, and remains central, for me.

You contend that poems should be spoken, not just read. Why?

The medium is the reader’s voice. At tonight’s reading, I hope to give a hint of what I worked to achieve in the vowels, consonants, intonations, rhythms, trying to make them like gestures that refine and focus the meanings.

What do you hope readers take away from Selected Poems?

Pleasure. A great feeling from hearing the sounds of meaning in the lines fitted to the tunes of the sentences.

Robert Pinsky will read from his new book, Selected Poems, tonight, Thursday, March 24, at 7:30 p.m. at the Photonics Center, Room 206, 8 St. Mary’s St. For more information, call 617-353-2821. The event is free and open to the public.

John O’Rourke can be reached at orourkej@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.