Remembering the Wigwam (Part Two)

BU’s Nickerson Field: former home of the Boston Braves

Red Sox fans file into Fenway Park today for the Sox opening day game against the Baltimore Orioles. But there was another major league baseball team—now largely forgotten—with indelible ties to BU. In this two-part series, BU Today recalls the long and storied history of the Boston Braves, who played on Braves Field—known today as Nickerson Field. Read part one here.

The fortunes of the Boston Braves improved dramatically after 1944, when they were sold to a trio of construction contractors, led by Lou Perini. These “Three Little Steamshovels,” as the press dubbed them, got to work signing talent like left-handed slugger Tommy Holmes. They also moved the right field fence in—to 320 feet from home plate. In 1945, the Braves hit 131 home runs, with Holmes alone scoring 28.

The modern Boston Braves’ golden age truly began when Perini hired star manager Billy Southworth to helm the club in 1946. A buzz began, and the timing—just after the end of World War II—was perfect. Veterans returning from overseas were craving normalcy: Mom, apple pie, baseball. People had a little more cash to spend than they had during the Depression. There were enough fans to fill the stands at both of Boston’s major league ballparks.

The ’46 season began with a hiccup. The grandstand seats were freshly painted, and damp weather meant the seats were still wet on opening day. Consequently, the paint ended up on the seats of patrons’ pants. Acting fast, the team offered to pay the cleaning bills of customers who requested it. The gesture generated goodwill rather than complaints, and the Braves’ postwar revival was on.

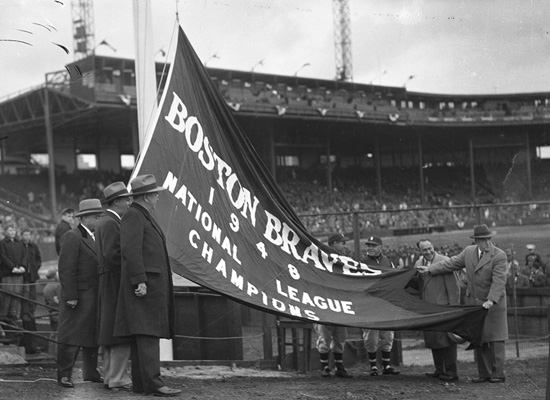

Hall of Famer Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain led a pitching staff of lesser-known hurlers. Some fans characterized the rotation as “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain,” inspired by a poem in the Boston Post about their pitching in the 1948 pennant race (they went 8-0 in 12 days). The team’s record and attendance numbers climbed steadily; in 1948, the Braves drew 1.5 million fans—and won the National League pennant for the first time since 1914. (Little-known fact: 1948 was also the year the Boston Braves cofounded the Jimmy Fund, a charity for cancer patients and cancer research that is now associated with the Red Sox.)

At this point, Boston was a hairbreadth from witnessing a streetcar series, as the Red Sox finished the season tied for first place in the American League. The Sox and Braves had played an exhibition city series every preseason, but a postseason World Series? A world of difference.

To break the tie and award the AL pennant, the league scheduled a one-game playoff between the Red Sox and the Cleveland Indians on October 4, 1948. Cleveland won. So instead of a streetcar series, baseball fans got a battle of the politically incorrect mascots.

On the plus side, a series that spanned regions rather than neighborhoods meant that fans (at least those with access to a television set) were treated to the first-ever nationally televised World Series, accomplished with the help of a B-29 bomber. Outfitted with TV equipment, the plane flew over western Pennsylvania to link the broadcasts of New England and Midwestern networks. (The Braves would again be pioneers in 1951, when they played the Dodgers in the first game televised in color.)

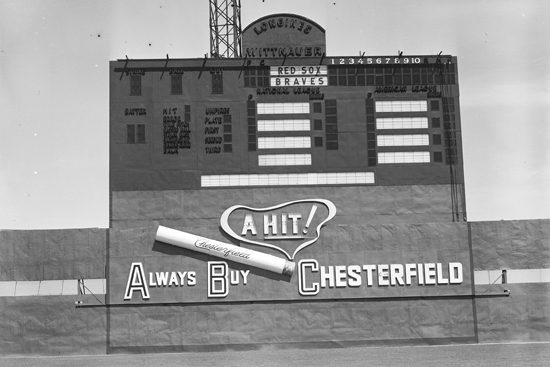

At game one, George Sullivan (CGS’53, COM’56,’76) was fortunate to get a seat in the Jury Box (right field bleachers) for a buck. The adolescent watched Sain outpitch Bob Feller as the Braves won, 1-0. “For some reason,” the Boston sportswriter recalled in a 2003 Bostonia article, “one of the images I remember most clearly from that day was fabled Cleveland pitcher Satchel Paige sneaking a cigarette behind the fence next to the bullpen during the game, an eye-popping sight for an impressionable 14-year-old who saw major leaguers as role models.” Not that bad habits were exactly discouraged at a ballpark where men drank beer and smoked cigars and the many outfield billboards, and even the scoreboard, were emblazoned with ads for Philip Morris and Chesterfield cigarettes, Narragansett beer, and Seagram’s whiskey.

Despite that strong start, the Braves fell to Cleveland in six games. As you may remember from the opening sequence of the classic 1989 baseball movie Major League, this world championship was a highlight for Cleveland before a decades-long slide. Well, the Braves’ slide began immediately. Nobody knew it then, but their seasons in Boston were numbered. Four, to be exact.

What if?

The Boston Braves went into free fall after their 1948 apex. In 1952, the team finished in seventh place and drew 281,278 fans for the season—what the Red Sox of the 21st century might draw in a home stand. In 1953, the Braves moved to Milwaukee.

Were the Braves marked by the hand of fate to leave the Hub? Not at all, says Tom Whalen, a College of General Studies associate professor of social sciences and author of several books on local sports history. The Tribe came within two wins of glory in ’48, “and it makes you wonder, if the Braves had been able to hang on and become World Series champions, would they have stayed? People forget, Hank Aaron was signed to a Boston Braves contract.” The future home-run king was still toiling in the Braves farm system (along with Joe Morgan—not the former Cincinnati Reds player and current television color commentator, but “Turnpike Joe,” the popular Red Sox manager of 1988 to 1991.) “Eddie Matthews and Johnny Logan had already been brought up. The core of the great Braves teams of the 1950s was already there” in 1952, says Whalen, “and they were just a year away from beginning their climb in the standings—the Braves’ first year in Milwaukee, 1953, they finished in second place.”

Meanwhile, “the Red Sox in the ’50s were on this downward slope to mediocrity,” he says. “They became kind of a laughingstock.”

The Sox had won a pennant in ’46, but wouldn’t win another until 1967. If the Braves had won just two more games to take the 1948 Series, the resulting bump in the club’s already-rising yearly attendance would have provided a cushion the team could have coasted on over those few rebuilding years until 1954, when Aaron joined Matthews and the others on the big club. In that case, Whalen says, “you gotta figure the Red Sox would have been the candidate to move, not the Braves.” There was even speculation throughout the ’50s and ’60s that the Sox might do just that, amid noise from owner Tom Yawkey to the effect that Fenway was an outdated dump.

Another what-if concerns the common belief that Boston was the last city to break the color line in baseball, Whalen says. True, the Red Sox were the last team in the majors to hire a black player, Pumpsie Green, in 1959. But the Braves debuted outfielder Sam “Jet” Jethroe in 1950, just a year after the Dodgers made history with Jackie Robinson. Jethroe was the National League’s Rookie of the Year in 1950. By 1952, the Braves had three African Americans on the roster, including George Crowe, Robinson’s onetime basketball teammate on the Los Angeles Red Devils.

“The Braves were far more progressive than the Red Sox,” says Whalen—and they weren’t alone among Boston’s major pro sports teams. The Boston Celtics also integrated in 1950, when they drafted Chuck Cooper to play basketball. “1950 was a banner year in Boston,” Whalen says. But when the Braves moved, they seemed to take the memory of that year with them. “Now when everyone around the country looks at Boston and thinks back, they point to the racist Red Sox organization of Tom Yawkey,” he says, and it feeds, a bit unfairly, into a larger perception of Boston as a city of bitter racial conflict. If the Braves hadn’t left, “Boston might have had a better reputation for race relations as a result.”

Incidentally (and speaking of the Celtics), Crowe wasn’t the Braves’ only dual athlete. Starting in Boston in 1952, Gene Conley pitched for the Braves and was also a backup center for the Celts, behind Bill Russell (Hon.’02). Conley is the only athlete ever to win championships in two of the four major professional sports—with the Milwaukee Braves in 1957 and the Celtics in 1959, ’60, and ’61.

Award-winning New England Cable News reporter Greg Wayland (COM’79) remembers his father taking him to the Wigwam for his first baseball game during what would turn out to be the Tribe’s final season in Boston.

“There was a huge bright and colorful image of the team’s symbol painted on the outer wall of the park just inside the ticket gates—those stucco buildings that are now the BU Police headquarters,” Wayland recalls. “An Indian with a feather dangling from his head, hand cupped around his mouth as he presumably issues a war whoop. You can imagine how a six-year-old kid would be awed by that.” The next time he would see that brave, the painting would be fading as an 11-year-old Wayland walked by it on his way in to a BU football game.

The big move—and aftermath

Although it was not planned this way, let alone announced that day, the Braves played their last game in Boston on Sunday, September 21, 1952.

At that time, Major League Baseball consisted of just 16 teams, clustered in 10 cities in the Northeast and upper Midwest. In an era when teams traveled by train, the rest of the country had to make do with minor league ball. No team had moved in the modern era. (Although later, the son of onetime Braves owner Judge Fuchs wrote that Henry Ford had personally scouted the Braves in the ’20s, hoping to move the team to Detroit.)

But Braves owner Perini had his eye on the future. “He actually wanted to move to the suburbs,” Whalen says. “He wanted a new stadium built, but he’d need a place to play in the meantime. He wanted to rent out Fenway Park. And Yawkey refused. That kind of pushed him out the door, to Milwaukee.”

In March 1953, while the team was at spring training, Braves management announced the move. Players found out when they got caps with an “M” instead of a “B.” Boston fans were shocked. Harold Kaese of the Boston Globe wrote an open letter to a Milwaukee fan. “Dear Sudsy…You are rolling out a red carpet for the Braves today, a lovely gesture towards a bunch of callus-toed ballplaying mercenaries. I hope you do not feel like burying them in that same red carpet come August.”

That wouldn’t be the last big structural change in Major League Baseball. Whalen says Perini set off a chain reaction. “The Braves had two and a half million attendance their first year in Milwaukee. Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley thought, well, now they can pay bigger bonuses, sign better players, and put us at a competitive disadvantage. How do we compete with that in the long term?” When O’Malley’s first plan, to build an enormous domed stadium in Brooklyn, didn’t pan out, he moved the team to Los Angeles in 1958, convincing Giants owner Horace Stoneham to follow him to the West Coast (San Francisco).

Later still, in 1966, the Braves would move to Atlanta, their fourth city since 1869. “Who knows?” Whalen speculates. “Maybe one day they’ll end up in Buenos Aires! The moon!”

What of Braves Field? Boston University bought the property in 1953 for $430,000 (the price today for a fixer-upper house in Boston). Even BU students who were lifelong Braves fans, like Sullivan, could take solace in that outcome. “The purchase was a bonanza for BU’s football players and other outdoor athletes,” he wrote. “No more traveling 13 miles to the old Nickerson Field in Weston, a daily round trip that required bumming a ride or taking a train from Back Bay station.”

That didn’t mean the end of pro sports at the field. It became the birthplace of the Boston (now New England) Patriots—a team owned by Bill Sullivan, onetime PR man for the Boston Braves. The Patriots played at Nickerson Field from 1960 to 1962.

What remains

The University tore down the Braves Field grandstands and left field pavilion to make way for the Sleeper, Rich, and Claflin residence halls, which were completed by 1964, and Walter Brown Arena, which opened in 1971. Viewed from the air, the semicircular arrangement of the dorms suggests the layout of seating around a baseball infield.

The right field pavilion remains intact—it’s now the main seating at Nickerson—along with a concrete wall in right and center field. Also still standing is the gatehouse and Braves front office—now the BU Police Department. Behind it, a plaque commemorates the Braves’ long tenure on the site.

And if you turn off Comm Ave and walk down Babcock Street, look down and to your right once you pass the MATCH school. You’ll see the trolley tracks that once carried young fans like Sullivan into the park on summer afternoons.

The attention of baseball fans is focused on Fenway Park this weekend, and rightly so, notes Whalen. “So much history of the game is here in these two parks. But in many ways, Braves Field is shortchanged. And we should never forget the Braves.”

Patrick L. Kennedy can be reached at plk@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.