BU Takes On Cancer: One Researcher’s Personal Crusade

SPH prof researches drugs to halt metastasis in breast cancer

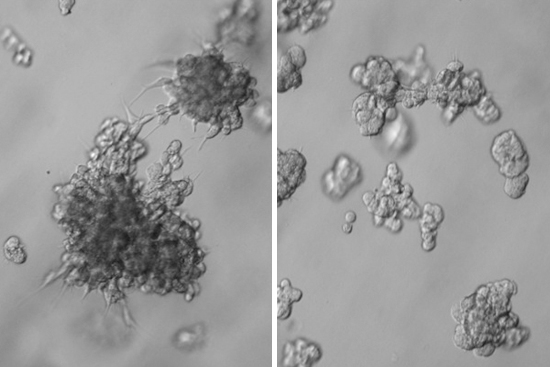

These slides show breast cancer cells before (left) and after exposure to experimental growth-retardants in David Sherr’s lab. Images courtesy of David Sherr

In the final part of a five-part series, BU Today examines the many ways BU researchers areworking to demystify, treat, and prevent cancer.

The photo collection snaking across two walls in David Sherr’s office includes a picture of a woman, her back to the camera, cradling a small child as they both scan the horizon. That snapshot of a second captures the pain of a lifetime, showing Sherr’s late wife, before she was diagnosed with the multiple myeloma that killed her a dozen years ago, holding their daughter.

“I have trouble putting that one of her up,” admits Sherr. “I’ve got to focus in here.” That’s because the School of Public Health professor believes he’s zeroing in on a chemical that might halt metastasizing breast cancer cells and make it easier for surgeons to remove them. His wife’s death adds fuel to his quest for a therapy for breast cancer, which annually kills an estimated 40,000 women and about a tenth as many men, trailing only lung cancer as the most lethal form of this disease among women.

Sherr’s work is promising enough to have won one of BU’s $50,000 Ignition Awards two years ago, money that paid for experiments demonstrating two possible chemical inhibitors of cancer cells. Now, he and his lab are seeking research money from a Dutch biotech company for the lengthy, expensive process of testing these potential drugs on lab animals, the run-up to human trials. (Researchers dub these costly hurdles separating basic science from a patient-ready product the “valley of death,” says Sherr, who is also on the School of Medicine faculty.)

Bottom line: even if everything pans out, any available therapy is likely a decade away. Still, what Sherr has seen under the microscope heartens him, and it begins with a long-windedly named protein, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR).

Thanks in part to research funded by the Art beCAUSE Breast Cancer Foundation, directed by BU alumna Ellie Anbinder (SED’62), scientists believe AhR is a prime culprit in the metastasizing of breast cancer. It signals cancer cells to lose their “Velcro,” Sherr’s metaphor describing the gene that pulls the cells together in one location. It also orders the cells to make enzymes that gobble up their surrounding environment, making invasion into surrounding tissue easier. Sherr believes that if we could neutralize AhR’s effects, we could halt the metastasis, making breast cancer a disease that can be lived with during a normal lifetime rather than a killer.

In the 1940s, a woman had a one in 14 chance of developing breast cancer over her lifetime; today, says Sherr (right), it’s one in eight. One theory for the higher risk is that modern life exposes us to more man-made carcinogens, a notion supported by research associating exposure to chemicals like dioxins with breast cancer. (Less than 10 percent of breast cancers come from genetic susceptibility to the disease, he says.) Those chemicals activate AhR to do its dirty work, which drew Sherr’s attention. “I got very suspicious that what it was doing was making cancer cells grow faster and invade,” he says.

Knowing what chemicals turned on AhR allowed Sherr and his colleagues to guess at the molecular structure of possible modulators for the protein. A computer search of more than one million molecules narrowed the possibilities, but they had to slog through more than 3,000 compounds before finding 3 chemicals they thought might do the trick.

They observed cancer cells in a tissue culture, doing what cancer does in a human body: invading and stretching out in tendrils to form oddball geometric shapes (below, left). Once the modulators are introduced, however, the cancer cells cluster together in tidier, rounder colonies (below, right), “like putting a fence around” them, says Sherr.

“Because they’re all sticking together, cancer cells cannot find their way across the tissue into a blood vessel and metastasize to some distant place,” he says, like the brain, liver or bones. “It’s that metastatic cancer that kills you.” Also, “If you’re a surgeon…as long as the tumor is contained, no problem—‘I cut it out, I zap it with radiation.’”

Unlike chemotherapy, the chemical modulators that Sherr is testing would not be toxic to the body. “We’ve got poisons we give people all the time, and it’s a horrible way to treat a disease,” he says. “It’s like a sledgehammer on a wall nail.”

The SPH researcher hopes that any drug he devises might combat other cancers, notably that of the brain, a hellishly difficult illness to treat. One study suggested the same receptor is at play there as well, says Sherr, who suspects the receptor helps fuel other aggressive cancers, too.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.