Huntington Stages Timely Political Drama

Now or Later set on eve of fictional presidential election

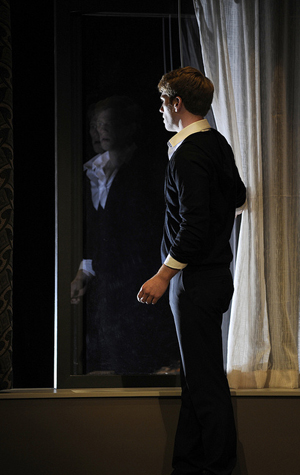

Tom Nelis, as John, Sr. (left), and Grant MacDermott, as John, Jr., in the Huntington Theatre Company’s American premiere production of Christopher Shinn’s Now or Later at the Calderwood Pavilion, Boston Center for the Arts. Photo by Paul Marotta

Christopher Shinn’s Now or Later is the 11th-hour story of a presidential election that hangs in the balance after photos of the incumbent’s son staging a potentially offensive prank are released on the internet. A taut drama for our electronic media-saturated, YouTube-dogged age, it touches on religious sensitivities, freedom of expression, and a father-son conflict that is as timeless as Shakespeare. Four years after its London premiere, Now or Later is making its American debut as the second play of the Huntington Theatre Company’s 31st season and is running through November 10 at the Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts.

Commissioned for London’s Royal Court Theatre, Now or Later was praised as “riveting, urgent, and unmissable” by the Times of London and a “gripping, daring” work by the Telegraph. Under the direction of Broadway director Michael Wilson (Enchanted April, Dividing the Estate, and Gore Vidal’s The Best Man), making his Huntington debut, the play unfolds in real time in a single hotel room. The suspense is fueled in part by the fact that “you never know who’s going to walk through the door,” says Huntington artistic director Peter DuBois, who calls Shinn “a playwright of big ideas.”

BU Today recently spoke with Shinn about the timing of his play’s American debut, what he learned from his mentor, Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award winning playwright Tony Kushner, and the death of nuance.

BU Today: Is it particularly exciting to have the play produced so close to a presidential election?

Shinn: It is exciting. I wondered when I wrote this play how the time it was produced would impact how it was received. It was something I couldn’t predict, but it’s something I knew I’d have to deal with. I wondered what different scenarios would mean for the play, and I guess I feel like audiences create relevance and connection if they want to, based on what’s happening in the world. There are so many ways to think about the play, and politics is so personal, that I knew there was no way to create a coherent or a universal way that people would see the play.

Now or Later debuted in London. How did British audiences react to it?

British audiences had a distance that allowed them to fully enter a fictional world. I wonder if that’s why it took the play four years to get done here. What was really interesting about my experience four years ago was how the British were obsessed with our 2008 election, in a very un-ironic way. They were flat-out fascinated. I think there are so many things about their system that led them to look at our system with some bemusement. Their elections are very short—an entire election for prime minister may take a couple of months—so our process is incredibly foreign to them.

Since you wrote the play, incidents of minor mischief like that of your character John, Jr., seem to happen a lot. Do you think events in the news alter an audience’s experience or expectations?

There’s really not much you can do about it. I remember in 2008 the play was in previews and the whole mini-scandal with Bristol Palin erupted, and there was a lot of focus on the child of a major candidate. Some critics thought I was very prescient, and others said, ‘This is the danger of writing this kind of play.’ One said the Bristol scandal was far more interesting. But the playwright always has to keep a strong sense of a fictional world.

You studied with Tony Kushner. In what ways was he an inspiration to you?

Tony was an inspiration in that he had incredibly exciting mind, and to be in the presence of his mind was to want to become the kind of person with that kind of mind. What I remember most vividly is thinking, I want to know what he knows, read the books he’s read. I was 19 or 20 when I first took his class at NYU, and it was an exciting moment of seeing my future before me. He told us we had to read the newspaper. I never had a teacher who spoke in those ways.

The play is fraught with tension, but except for one moment there is little physical action. How have audiences reacted to this scene?

I remember in London, it was powerful; it felt like an emotional moment. I think that I just want everything to be truthful, so the challenge with a play like this is, even when characters are talking about ideas, to make the audience feel they’re really human beings in relationships with each other, and experience all the tension and conflict that have been building.

The president’s gay son, John, Jr., questions his father’s commitment to gay rights. In an interview, you describe growing up gay as miserable and say that homosexuality is a profoundly complex and divisive issue. Is this still the case and are you hopeful that it will change?

I think it’s a complicated answer. Given the gay marriage bill, and the fact that the Supreme Court will hear the case very soon, I think things are definitely getting better. But I do think homosexuality will always be a taboo. The only way society survives is by its citizens reproducing. There will always be tension between supporting personal freedom and the aims of the society itself. So even though I do think that increasingly, gay people will be protected by the law and have civil rights, I don’t think there will ever come a time when homosexuality won’t be a taboo.

Tell us about the challenges of writing a play that unfolds in real time.

I’d never done it before, and I wanted to give myself that challenge. You have to find a way to keep it interesting without stopping and jumping to a more interesting moment. It means being very economical and very clear about finding reasons to put the characters there. If the play’s set in a hotel room, I have to find an excuse for many people to enter the room. Actually a lot of the inspiration for the play came from that challenge. I definitely thought a lot about Greek tragedy when I was writing it.

John, Jr., struggles to convey his nuanced reasoning for not apologizing for his actions, yet his father and his father’s aide are prepared to capitulate to a public that sees everything in black and white. Are you troubled by the lack of nuance in society?

I do think it’s a problem. This makes it really hard to be an artist, but harder to be a politician. It seems like you are not allowed any complexity. I feel like my task as a playwright is to balance complexity with accessibility, but I don’t want to dumb down my work. I guess I always felt like you can have it all if you work hard enough. I think complexity was more valued in society 15 or 20 years ago when I was just starting. I often wonder, if I were beginning my career now rather than in 1998, what kind of artist would I have become? Would I feel there was enough support to try to go deep?

Are there things about America today that sadden you?

I think we’ve given up tragic thinking. I make the comparison to a time years ago when Freud was writing about the deepest currents in the psyche and civilization and wondering if humans could survive the destruction of our nature. Today we use neuroscience and psychology to craft theories about how you can have a leg up. We’ve replaced the dark, tragic thinking of Freud with the very superficial thinking of Malcolm Gladwell, allowing people to feel smart without asking any of the profound questions. I look at the period of Camus and Sartre, that moment in the 20th century when great minds were trying to understand the overwhelming complexity and madness of human life, and I feel like that’s almost completely gone. We’re flat and commercial-minded.

What has it been like working with the Huntington for the first time?

It’s really exciting to be in a major city in a theater with extraordinary resources and to feel immensely supported by the theater community and also the broader community. So far it’s been a very inspiring experience.

Why should college students go see your play?

Why not go? Give my play a try. I’m trying to write plays that are very broadly accessible and deal with the world we live in.

Now or Later runs through November 10, 2012, at the Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts, 527 Tremont St., Boston. Tickets may be purchased online, by phone at 617-266-0800, or in person at the Calderwood Pavilion box office. Patrons 35 and younger may purchase $25 tickets (ID required) for any production, and there is a $5 discount for seniors. Military personnel can purchase tickets for $15, and student rush tickets are also available for $15. Members of the BU community get $10 off (ID required). By public transportation, take the MBTA Green Line to the Copley Square stop or the Orange Line to Back Bay. Follow the Huntington Theatre Company on Twitter at @huntington.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.