Huntington Theatre Company Turns 30

Managing director reflects on first three decades

Walk into Michael Maso’s office and the first thing you notice are the walls. They are covered nearly floor to ceiling with show posters, photographs, and props—all bearing witness to the Huntington Theatre Company’s remarkable 30-year history. One poster commemorates Kate Burton’s performance in Hedda Gabler (2000–2001 season), another Esther Rolle’s in A Raisin in the Sun (1994–95 season), a third Campbell Scott’s in Hamlet (1995–96).

There are also the framed Tony Award nominations for Huntington productions the company helped to transfer to Broadway, attesting to its place today as one of the nation’s preeminent regional theaters. Three nominations—the Huntington has been nominated four times for Broadway’s highest honor—were for premiere productions of August Wilson plays: The Piano Lesson, Two Trains Running, and Seven Guitars. (The fourth nomination was for 2008’s The 39 Steps.) A framed photograph of Maso with Wilson (Hon.’96) holds a place of honor over his desk.

If Maso’s office feels like a theater archive, it’s only fitting. He is the only Huntington staff member who has been here from the beginning, in 1982. As the company’s managing director, he has presided—by his own count—over approximately 185 productions, and over the years has worked with three different artistic directors (Peter DuBois currently holds the post).

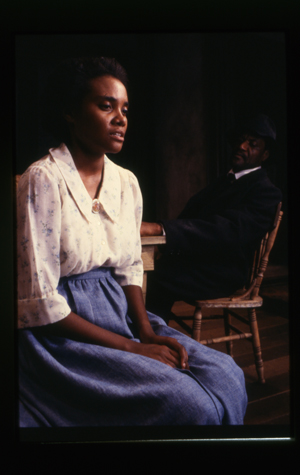

Ask Maso to name a few of his favorite productions and he glances around the walls to help dredge up memories. “The most transformative production I think we’ve ever done,” he says, “would be that first August Wilson play, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, which many of us think is his masterpiece.” To mark its 30th anniversary, the Huntington has mounted a production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, the only one of Wilson’s 10-play “Century Cycle” not previously produced by the company. It is running at the BU Theatre through April 8.

Maso quickly names other well-loved productions: the 1987–88 season’s Animal Crackers, the classic Marx Brothers comedy; a series of Gilbert and Sullivan musicals that launched with H.M.S. Pinafore in the 1990–91 season; The Woman Warrior, an adaptation of two of Maxine Hong Kingston’s books, in the 1994–95 season; and last year’s world premiere of Stephen Karam’s Sons of the Prophet, which went on to Off-Broadway.

And then there are the performances. Sitting in his office across the street from the BU Theatre, the Huntington’s 900-seat proscenium theater, Maso cites as standouts Tony Award winner Phylicia Rashad in Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean, Brooks Ashmanskas in the musical She Loves Me! and local actors Will Lyman (CFA’71) and Karen MacDonald (CFA’72) in Arthur Miller’s All My Sons.

Talk inevitably focuses not just on transcendent productions and star-turns, but also on the nearly averted disasters inevitable in live theater. Maso recalls the opening night of Seven Guitars, starring a young Viola Davis, recently nominated for an Academy Award for The Help. During one early, pivotal scene, Davis was supposed to open a door on the set and turn a radio off, setting up the next scene, but the door jammed. Before a high-powered crowd of critics and commercial theater producers, Davis tugged on the door repeatedly, to no effect. Another actor tried to cover for her, but the production had to be shut down for 10 minutes to replace the doorknob. The play then started over from the top. A similar mishap occurred on the opening night of Tom Stoppard’s Jumpers—this one involving a moving platform during the opening monologue. “It just stopped dead,” recalls Maso, wincing at the recollection. “Two opening nights where we had to stop right in the beginning and fix something and start again

Training—in offices, scene shops, costume shops, rehearsal hall

During his interview for the managing director job, Maso recalls asking why Boston University was interested in launching a professional theater company. He was told that John Silber, then president, had said that if BU can support a football team, it can support a theater company (BU still had a football team in 1982). Maso, a College of Fine Arts School of Theatre associate professor, says that Silber (Hon.’95) is responsible for providing critical support for the company’s founding. “Dr. Silber understood that Boston was unique in being the largest city in the country without a major resident theater, as the anchor for the theater community. It didn’t exist,” he says. “Silber is somebody who really understood the value of the arts in the life of a city, the value of theater in the life of community, and he thought, this is something the University can make happen.”

In addition to providing the Huntington with a theater, BU also aided the company with crucial funding—as much as 50 percent of its annual operating budget—during its early years.

In 1986, the Huntington Theatre Company legally separated from BU and incorporated as a separate entity. Both parties, Maso says, realized that the company needed to be an independent entity that could build a broad-based coalition of support. But the two remain intertwined: the University continues to lease the theater to the Huntington rent-free, and it provides some financial support (about 2 percent of the annual operating budget). In exchange, the theater company runs the facility and the staff builds the sets for one of the two BU Opera Institute operas each year.

But, according to Maso, the most important thing the Huntington provides BU is training opportunities for theater majors. “We’re one of the tools the University has to give professional experience to students and to send them out into the marketplace better prepared technically, but also better prepared to navigate a business which is not always easy for young people,” he says. “Students are involved every day at the Huntington. They’re involved in our offices, they’re in our scene shops right now, they’re in our costume shops, they’re in the rehearsal hall.”

Just as BU’s relationship with the Huntington has changed in the intervening years, so too has the company’s mission, he says. What began as “a sort of writer-based theater, where we were doing classical work and contemporary work,” has developed into a much larger mission. Today, the company runs an extensive educational program for some 30,000 high school students each year. And, after funding and building the two theaters that make up the Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts in 2004, its community involvement is even more pronounced: through the Calderwood, the Huntington serves 40 different local theater companies a year who lease the space, and it also supports an ambitious two-year residency program for emerging writers.

The Calderwood’s two theaters also provide the Huntington with smaller venues for staging more intimate productions, such as the critically praised Stick Fly, by Lydia R. Diamond (GRS’09), in 2010. The CFA assistant professor’s play was mounted on Broadway this past December.

The company operates on an annual budget of approximately $13 million, with $3 million coming from subscribers. Like most arts organizations, the recent economic recession has forced the company to make some tough decisions, Maso says. “We got smaller by about 15 percent. We lost about 15 percent of our staff, we lost about 15 percent of our operating budget from 2009 to 2010, and then sustained those decreases.” But the cuts were made in a way that “didn’t really affect our programming.”

For Maso, the company’s 30th anniversary isn’t so much an occasion to look back as an opportunity to look ahead. He has hopes of creating an innovation fund that would allow the Huntington to produce special projects it couldn’t otherwise afford. And he’d love to see more Shakespeare on the stage. “We’ve done Hamlet, we’ve done some of the comedies, but there are lots of histories or tragedies that we haven’t done.” There’s talk of producing some Edward Albee (Hon.’10) plays. And Maso would love to see the Huntington stage Lorraine Hansberry’s rarely produced The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which he concedes would be hard because of its enormous scale.

“I think we’re at a time when we still haven’t quite set the Huntington in stone,” Maso says. “We haven’t quite yet created a permanent institution. I think that we still have some work to do to make sure we’ve secured this institution for future generations. And I think that’s enough of a job—that interests me still.”

Michael Maso will be honored with the Wimberly Award for his three decades of service at a gala fundraiser for the Huntington Theatre Company tonight, Monday, April 2, at the Park Plaza Hotel Ballroom, 50 Park Plaza at Arlington Street, Boston. The event is hosted by Tony Award winner Joanna Gleason. More information about the 2012 Spotlight Spectacular gala, which begins at 6 p.m., can be found here.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.