Nights of the Roundtable

"Orgy of the mind"—science meets religion over dinner

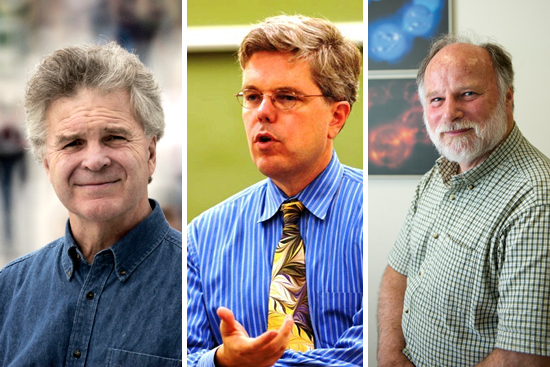

BU attendees at recent Cambridge Roundtable forums include H. Eugene Stanley (from left), Kevin Outterson, and W. Jeffrey Hughes. Stanley photo by Kalman Zabarsky. Outterson photo courtesy of Kevin Outterson. Hughes photo by Cydney Scott

Science and religion often make such incendiary bedfellows that even as arid-sounding a lecture as The Self-Disclosure of Ultimate Reality can summon the culture warriors. In 2005, that talk kicked off the Cambridge Roundtable on Science, Art, and Religion, a dinner forum of scientists and theologians from BU and nearby universities seeking to learn more about one another’s bailiwick. The speaker was physicist and Anglican priest Sir John Polkinghorne, who discussed intelligent design, the notion that the universe exhibits a precise order that might be the work of a divine architect. Held at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, the talk disgruntled some who worried that the locale either suggested scientific sponsorship of the event or would give ammo to religious activists disputing evolution.

The dustup arguably validated the roundtable’s founding goal: dialogue between academic and Christian thinkers, says cofounder Dave Thom. An MIT chaplain, Thom continues to organize the invite-only dinners, the most recent—God, Stephen Hawking, and the Cosmos: Is There a Grand Design?—in February. University professors who have attended these nights of the roundtable find them, in College of Arts & Sciences physicist H. Eugene Stanley’s phrase, an informative “orgy of the mind.”

“I want to explore issues that are not science,” says Stanley, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor. Nonreligious save for the Shabbat dinners he shares with family every Friday, Stanley nonetheless has “an incredible awe for things, whether it’s a baby being born or a flower blooming,” that’s nurtured by the roundtable discussions.

The roundtable typically gathers twice a year and can draw more than 100 attendees, mostly from BU, Harvard, Tufts, and MIT. The idea is that both Christian and non-Christian perspectives benefit from accurate, constructive criticism by outsiders, says Thom. “Without the help of insight from an atheistic literature professor, a Christian biology professor might not get the best feedback he needs to shape his views on biology or Christ or literature,” he argues. “I know of no other similar vehicle for open discussion at any elite university setting.”

Tables mix scientists with theologians, the latter in attendance usually because they’re “teaching as opposed to preaching,” says W. Jeffrey Hughes, an astronomy professor and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences associate dean.

Topics have included Can Atheists and Theists Agree on What Constitutes a Meaningful Life?; Does the Universe Suggest Evidence for God?; Can We Be Good Without God?; Evangelicals and the Academy; Religious Literacy; and Should Intelligent Design Be Taught as Science in the Secular University? (advocates pro and con fielded that one). Speakers have included Stephen Prothero, a CAS professor of religion, and George Siscoe, a CAS research professor of space physics.

“The format is generally a provocative talk by a well-known speaker, followed by a commentary by a local professor,” says Kevin Outterson, a School of Law associate professor, who has attended several talks. “The first speaker is generally not speaking from the Christian perspective, but is raising questions that relate to faith generally.” Time is allotted for diners to talk over the night’s topic at their tables, he says.

Religion is a crucial part of Outterson’s life. He attends the nondenominational Vineyard Christian Fellowship church in Cambridge, advises the Law Christian Fellowship (a student group), and helps lead the Boston Faculty Fellowship, a group of Christian professors from BU and nearby universities. “Faith is important to many people, whether they belong to an organized religion or not,” he says. “It would be absurd for universities to talk about everything except faith. A core value of the university is that every topic, every perspective, is fair game.”

Stanley’s research involves statistics and unpredictable events, and he values the hard, empirical work of science. “But that’s not what all life is about,” he says. “Otherwise, we would just work 168 hours a week.” He’s also interested in ethics (putting his own into action when he advocated for Soviet refuseniks beginning in the 1970s), about which religion has a lot to say. Nor, says Stanley, do you need science to enjoy an art gallery, love your children, or marvel, as he does many nights from his 14th-floor apartment, at the beauty of the moonrise.

“All of us, in our research and intellectual pursuits, tend to be pretty narrow,” says Hughes, who enjoys the roundtable for broadening the conversation outside of science, “which I think scientists do less than the humanists.

“It’s a forum in which the question of how science and religion interact and intersect is what you do, whereas in most scientific discourses, you completely ignore that. What does it mean to live a good life? Who asks that question in class? Maybe some philosophers. But every person should be asking that question, and how do you put that into practice—a moral education, if you like.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.