One Address, Many Stories

Shelton Hall’s stately, swinging past

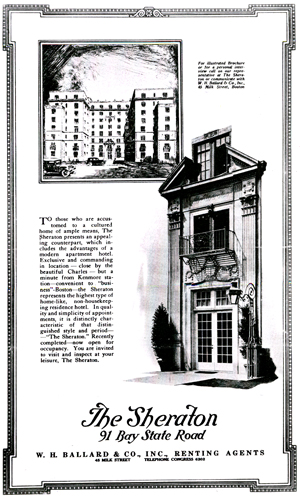

Once home to playwright Eugene O’Neill and Red Sox slugger Ted Williams, the residence hall formerly known as Shelton has a history of being renamed. Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

The last .400 hitter in major league baseball, a star of the silver screen, and America’s leading playwright all lived in the stately hotel. Big bands played on the roof for decked-out dancers and a national radio audience. A blue-blooded senator and a Catholic cardinal addressed meetings here, and the chief of Clan MacLeod once arrived with a flourish of bagpipes and a ceremonial haggis direct from Scotland.

It all happened in the building known to the Boston University community—until this week—as Shelton Hall. The dorm at 91 Bay State Road is about to get a new name, but not for the first time. (And no, there was no BU founder or president—or anyone, for that matter—named Archibald Cornelius Shelton.) In fact, Kilachand Hall will be the building’s fourth official name in the almost 90 years it has stood here, overlooking the Charles River.

A residential hotel?

In 1923, the newly formed Bay State Road Company erected a “thoroughly modern eight-story, fireproof apartment building,” the Boston Globe reported, “in the center of one of Boston’s most exclusive and highly restricted districts,” where the Back Bay meets Kenmore Square. They called their enterprise the Sheraton Apartment Hotel, or less formally, the Sheraton Apartments.

There was not yet a Sheraton hotel chain, and the developers likely chose the name to evoke the furniture style popularized by famed English furniture designer Thomas Sheraton in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The building itself recalled that era—the Federal period—with understated neoclassical touches. It was designed by the same firm that created Boston’s original Ritz-Carlton (now the Taj Boston) overlooking the Public Garden.

The patio-fronted H-shaped edifice housed “132 apartments, arranged in suites of one and two rooms with bath,” said the Globe, noting the rooms were “exceptionally large, and more than half of them [command] a view of the Charles River Basin.”

So was it an apartment building or a hotel? In those days, the lines between the two could blur.

“The residential hotel was a phenomenon from 1850 to 1950,” says Bradford Hudson, a School of Hospitality Administration professor of marketing and business history. As cities grew in size and density, “America was experimenting with new forms of real estate,” Hudson says. “It was 100 years of trying to figure out how to live.”

The Sheraton and the many places like it housed long-term residents in small apartments, without signing them to long-term leases. They boasted a lobby with a concierge who screened visitors, linens and maid service, and a dining room. Often, they hosted social functions, such as the weekend dances at the Sheraton’s open-air rooftop nightclub.

The high-end residential hotels like the Sheraton appealed to what Hudson calls “high society on the move”—that is, wealthy executives and their families who wanted to stay in a city for an extended period without the hassle of overseeing servants, cultivating a garden, or hosting elaborate dinners.

What’s in a name?

Throughout the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, the Sheraton was a social institution. The Globe’s gossip and nightlife pages were full of stories of prominent newlyweds moving in, gourmet Thanksgiving dinners served by waiters in white coats, and nights of entertainment featuring jazz bands and bandleaders such as Ranny Weeks, Meyer Davis, Cy Delman and his Kentuckians, and Johnny Cole’s Sheraton Roof Orchestra. As formally attired guests dined, imbibed, danced under the stars, and took in panoramic views of Cambridge, Boston, and the Charles from the rooftop ballroom, CBS and NBC aired the swinging tunes over the radio waves. And throughout the week, local radio station WBMS broadcast from a studio inside the building. Hosts included Sabby Lewis, one of Boston’s first African American radio personalities, and Mayor James Michael Curley, who offered commentary and recited his own poetry.

Celebrities who lived in the building at one time or another included singer and actress Jeanette MacDonald, who starred in nearly 30 MGM films in the ’30s, Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox, perhaps the greatest hitter who ever lived and the last man in the majors to bat over .400 for a season, and playwright Eugene O’Neill (more on him later).

The building’s first change of ownership came in 1939, when Ernest Henderson and partners bought the Sheraton from the Bay State Road Company. At the time, Henderson owned a few other hotels and hoped to establish a large chain under a single name. SHA’s Hudson points to a passage in Henderson’s autobiography that explains the rest:

“We had acquired the Lee House in Washington and a hotel known as the Sheraton on Boston’s Bay State Road. The latter, having an expensive electric roof sign, left us little choice in selecting the name for our future domain, for it would have cost a small fortune to change the letters on the sign. Our hotels in Springfield and Washington became Sheraton hotels.”

Indeed, Henderson renamed his entire company Sheraton, and the now-famous hotel chain was born. Today, there are more than 400 Sheratons worldwide (now part of the Starwood corporation).

In 1950, the Sheraton on Bay State Road changed hands again. The new owners, the Sonnebend family, did have money to alter the neon sign on the roof, but (as evidenced by contemporary photographs) only enough to change the RA to an L to create the Hotel Shelton. The Sonnebends also kept in use all the old linens, embossed with an ambiguous S. What they could not change were the words “The Sheraton” engraved in limestone over the front entrance. That evidence of the building’s origin remains to this day.

The Shelton continued to host social events and other gatherings in the early 1950s. Richard Cardinal Cushing, archbishop of Boston, and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., gave speeches warning of the global Communist threat. Ham radio operators fêted Walter Butterworth on his retirement as a top Federal Communications Commission official. And Dame Flora MacLeod, chief of Clan MacLeod, addressed the Scots Charitable Society after ceremoniously escorting in a dish of haggis imported from the Isle of Skye.

The spirit of a genius

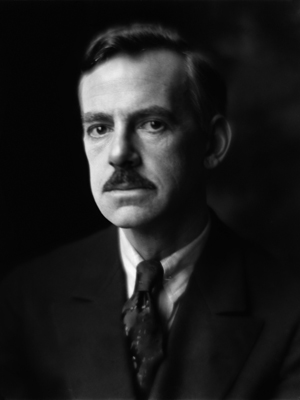

It was to the Hotel Shelton that playwright O’Neill moved in 1951.

Son of an alcoholic actor, O’Neill was expelled from Princeton and dropped out of Harvard to work as a gold prospector, a mule tender, a steamship seaman, and a newspaper reporter before he found professional success writing plays that brought a new maturity and realism to American theater.

O’Neill’s first play to be produced on Broadway was Beyond the Horizon in 1920. His other works include Anna Christie, Strange Interlude, which was banned in Boston in the ’30s, The Iceman Cometh, and A Moon for the Misbegotten. To date, O’Neill is the only playwright to win both the Nobel Prize and four Pulitzers. “Before him, there was nothing American of note on the stage,” wrote a later critic. “People saw Shakespeare and sentimental fare” until O’Neill “gave them a searing look into the bitter truths of life.”

Suffering from a rare neurological disease called cerebellar cortical atrophy and bronchial pneumonia, O’Neill spent his last days in Room 401 of the Shelton, tended by his third wife, Carlotta Monterey. “I knew it,” he is said to have uttered toward the end. “Born in a hotel room and, goddamnit, died in a hotel room.” Sure enough, he died in the Shelton in November 1953 at age 65. The Globe eulogized him as “the brooding genius of the American theatre.” (His masterpiece, the autobiographical Long Day’s Journey into Night, would not be produced and published until after his death.)

In 1954, BU bought the building at 91 Bay State Road, modifying the name to Shelton Hall. It became a women’s dormitory for about 475 students.

“Men were not allowed past the first floor,” says Jennifer Battaglino, Shelton’s residence director. “Male visitors had to hang out with their female friends on the first floor,” in the lobby or dining room, under the watchful eye of no-nonsense faculty or staff advisors.

The rule was broken for various social occasions, however. Harking back to its hopping hotel past (and continuing into the present), Shelton Hall hosted Halloween parties, charity fundraisers, and semiformal student dances in the dining room and on the roof—which was eventually enclosed, but in glass, preserving the excellent views. Indeed, Shelton, a residence largely for upperclassmen even after going coed in the ’70s, was the most sought-after dorm on campus before the Student Village was built.

But the spirit of O’Neill, whether literal or figurative, hasn’t entirely left the building. In addition to academic specialty floors devoted to engineering and management, Shelton features the Writers’ Corridor—students who are aspiring writers live on the fourth floor, where O’Neill lived (and died).

“Students say they hear knocks on their door and when they go to check, no one will be there,” says Battaglino, who has experienced some mysterious elevator malfunctions (the door opening on the fourth floor for no reason). Residents also cite the dim lighting in the hallway, relative to the rest of the dorm, although Battaglino has a mundane explanation: the ceilings are lower, covering the space on the other floors where there are extra rows of lights.

David Zamojski, for one, is not a believer. As Shelton’s hall director in the 1980s, “I lived on that floor for six years,” says Zamojski, now assistant dean of students and director of residence life, “and I never saw or heard anything strange.”

But whether the odd bumps in the night are the work of the playwright or of pranksters, the student scribes appreciate the floor’s history as home to a great American writer. “They say they get inspiration from O’Neill’s writing,” says Battaglino. Students regularly gather for writers’ workshops, where they read and critique one another’s work, and every year they release a compilation of their stories, essays, and poems, called “Eugene’s Legacy.”

Joining the writers, engineers, and managers next year, thanks to a $10 million gift from BU trustee Rajen Kilachand (GSM’74), will be students enrolled in the cross-disciplinary Kilachand Honors College. These new residents will further enrich the life of a residence hall that maintains elements of its stately, swinging past.

“It still is a beautiful place,” says Zamojski. “There’s so much original architectural detail in the lobby, it’s in a great location—students love living there.”

Patrick L. Kennedy can be reached at plk@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.