The Addiction Puzzle, Part 4: Why Alcoholics’ Gender Matters

MED's Berman finds men's, women’s brains affected differently

“When you’ve been drinking heavily for a long time, you change the whole chemistry and structure of your brain.”

Drug or alcohol addiction affects nearly 23 million Americans and costs the United States an estimated $428 billion each year. Modern science has dispelled many misconceptions about the disease and scientists are working hard to find effective treatments. At Boston University, more than 100 researchers have been awarded over $130 million in addiction-related research and services grants since 2006, and faculty currently direct over 50 funded addiction-related research projects.

Still, many questions remain: why do some people become addicted and others don’t? Why are some recovering addicts able to maintain sobriety while others have chronic relapses? Does evidence-based research contradict what has been assumed to be effective screening and treatment programs? In what ways does addiction impact men and women differently?

This week, BU Today is repeating its weeklong series, “The Addiction Puzzle,” examining the work of five BU investigators.

Although long-term chronic alcoholism ultimately destroys the bodies as well as the minds of men and women, it treats the genders differently. For one thing, women tend to get drunk more quickly, and according to data compiled by the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA), they are more likely to develop cirrhosis of the liver after fewer years of drinking than their male counterparts. But historically, drug and alcohol abuse have been viewed as affecting mainly men, and science is only now catching up, says neuropsychologist Marlene Oscar Berman, a School of Medicine professor of anatomy and neurobiology, psychiatry, and neurology, who studies the effects of long-term chronic alcoholism on the brain.

As alcoholism grows among the female population, research on its long-term effects is expanding to reflect what is becoming, especially among younger women, an equal-opportunity affliction. Berman is at the forefront of that basic research. By correlating subjects’ brain scans with their drinking histories, she has discovered what appear to be compelling, complex neurological differences in the brains of alcoholic men and those of alcoholic women. Her data make a strong case for broader examination of gender differences among alcoholics, which could pave the way for more individualized, effective treatments.

Although the NIAAA, part of the National Institutes of Health, estimates that alcohol abuse in the United States is twice as common among men as it is among women (5.5 percent versus 1.9 percent), rates of both alcohol and drug abuse are reported to be about the same among younger adults. “Neglecting consideration of gender as a factor in alcoholism studies is unfortunate,” write Berman and coauthor Susan Mosher Ruiz (GRS’12), a postdoctoral neuroscience fellow, in a recent editorial in the journal Alcoholism & Drug Dependence. Women process alcohol differently, not only in the central nervous system, but overall, since women tend to be smaller than men, with lower water volumes and higher peak blood alcohol concentrations because of a less active enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase, Berman explains. In plain terms, it takes less alcohol for women to get drunk. That’s why moderate alcohol intake is defined as one drink for women, two for men.

Among its many ravages, from liver disease to some cancers, alcohol takes a toll on the brain. Specifically, it shrinks brain tissue, with the degree of risk, damage, and reversibility varying with age, drinking history, nutrition, and, as Berman’s studies support, gender. The NIAAA estimates that half of the nation’s 20 million alcoholics suffer cognitive impairment, and up to 2 million develop permanent, debilitating conditions that require lifetime custodial care. Her investigations have been funded by the NIAA and the US Department of Veterans Affairs since the 1970s.

“When you’ve been drinking heavily for a long time, you change the whole chemistry and structure of your brain,” says Berman, who has studied brain damage in animals and humans for about four decades. Before the availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which produces detailed real-time pictures of soft tissues without exposing subjects to radiation, she assessed how alcoholics functioned and how that might have reflected changes in their brains. But she could not directly map and measure those changes. Since then, with an impact to scientists akin to giving a blind man sight, neuroimaging has proven what researchers had long suspected: long-term alcohol abuse alters the brain’s white matter, the clusters of neurons that allow the five major regions of the brain to communicate with one another. The MRI scanner enables Berman and her team to compare and analyze blood flow, one relative indicator of brain activity. When it comes to examining gender differences, the images not only offer evidence of those differences, but they could pave the way toward eventually understanding the differences in what motivates men and women to drink, says Gordon Harris, director of the 3-D Imaging Service at Massachusetts General Hospital, who is working with Berman’s team.

Alcoholism’s effects on the brain’s master circuit board

While many studies have focused on assessing the often obvious ways alcohol can affect the frontal lobes—the part of the brain involved in emotion, impulse control, judgment, and social and sexual behavior—Berman was among the first neuroscientists to shift attention to the effects of alcoholism on white matter, the brain’s master circuit board. She compares white matter, its nerve cells wrapped in insulating myelin, to the thousands of wires clustered inside a telephone connection box. The loss of white matter in alcoholics is likely to be related to many of the insidious long-term effects of chronic alcohol addiction, including memory problems, impaired thinking, emotional imbalance, and flat affect.

In these comparative MRI scans of two 72-year-old women, the brain of the alcoholic (top) clearly shows thinning and atrophy in several areas of the brain, particularly the clusters of nerve cells known as white matter. Image courtesy of Marlene Oscar Berman View full size

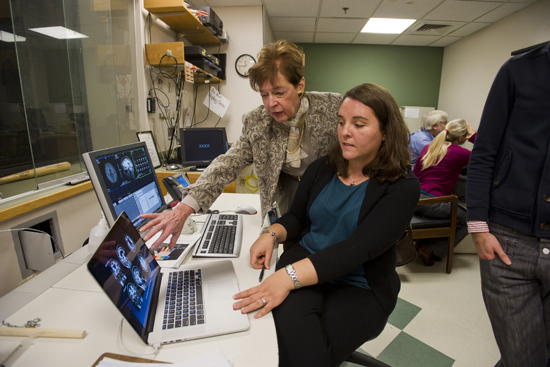

In her studies, based at the VA Boston Healthcare System in Jamaica Plain, where she is a career research scientist, and the Charlestown Navy Yard branch of MGH, Berman and her team examined brain images from 42 abstinent alcoholic men and women who drank heavily for more than five years and from a control group of 42 nonalcoholic men and women. The results, which appear in a recent issue of Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, showed that the more years the alcoholics had abused alcohol, the smaller their white matter. But in the men the decrease was observed in the corpus callosum region—a flat bundle of nerve fibers making up the bulk of white matter—while in women the effect was seen in regions of cortical white matter, which connects it to another major hemisphere known as gray matter, says Berman, who is also director of BU’s Laboratory of Neuropsychology and recipient of an International Neuropsychological Society Distinguished Career Award and a Massachusetts Neuropsychological Society lifetime achievement tribute.

It appears that in recovery, the genders differ as well. When Berman looked at recovery of brain volume in the men and women given MRI scans, she found another, more surprising discrepancy. “The findings suggest that restoration and recovery of the brain’s white matter among alcoholics occurs later in abstinence for men than it does for women,” she says. “We found that in men, the corpus callosum recovered at a rate of one percent for each additional year of abstinence.” But for those who’d abstained from drinking for less than a year, she found evidence of increased white matter volume in the women, but not the men, who showed no signs of recovery until after a year.

One way that Berman’s work is unusual is that “we compare data within a group of people who have already quit,” says researcher and neuroscience doctoral student Kayle Sawyer (MED’15). “We’re not measuring a person’s function when they quit drinking and then again five years later to measure improvement. That’s not the kind of data we have.” The team instead looks at specific brain functions and tries to correlate them with factors like the duration of a subject’s heavy drinking or the amount they drank.

Gender: small piece of large, unwieldy puzzle

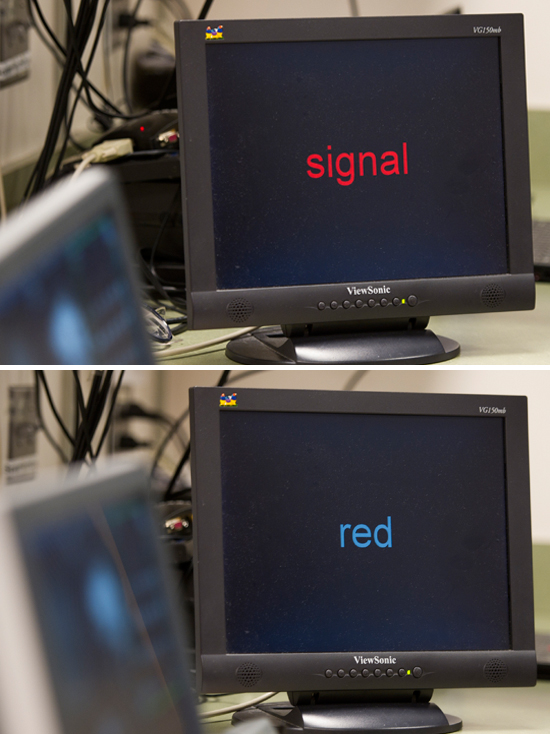

Berman, along with Sawyer and Ruiz, is also conducting studies in which former alcoholics undergo MRI scans while performing memory tasks. While in the dark scanning tube, the subjects use hand controls to answer seemingly simple questions, some designed to trick the brain, flashing swiftly on an overhead screen. Subjects get a chance to prepare a bit with test runs and a printed guide, so that by the time they’re in the scan their fingers can find the right response buttons by memory. The task then flips from responses based on color to responses based on words. And it all happens fast. “It’s not easy,” says Ruiz, who communicates with, and reassures, subjects through an intercom.

To compare more subtle differences between the alcoholic and the nonalcoholic brain and its responses, Ruiz has also looked at how abstinent alcoholics react to provocative photographs, which can be anything from bottles of Coke, coffee, alcoholic beverages to images of violence. “It’s a very complicated paradigm, but essentially a person looks at something that he’s supposed to remember, and then is shown pictures of beverages, which are supposed to have a greater effect on brain activation in alcoholics than they do in nonalcoholics,” she says. “It’s a kind of incidental stimulus. We look at what these images do to the brain—brain activity is registered on MRIs as the result of changes in cerebral blood flow.” In these tests, subjects view the series of images while undergoing an MRI, and respond by pressing buttons on a handset. One former alcoholic, who had been sober for 17 years, said in mid-scan, “Get me out of here,” because the images so powerfully stirred her desire for a drink. “We gave her some crackers and water, and she went to see her counselor,” Ruiz recalls. “She was fine, but what amazed me is how this desire to drink could be so powerful even 17 years later.” In a separate study, Sawyer is looking at how the thickness of the brain’s surface—the cortex—varies depending on how long people drink, how many drinks they had a day, how long they’ve been sober, and other questions.

Participation in Berman’s studies, which involve relatively small samples, is rigorous, and subjects are paid for their time. The scans alone can take up to two hours (claustrophobics need not apply), but the initial screening process is also demanding, consisting of an initial interview, a psychological workup, a series of memory task tests, and questionnaires about potential subjects’ medical and educational backgrounds. “We can’t control what we call comorbidities—anxiety, depression, drug use, smoking—in our subjects,” Sawyer says, “so we look at realistic situations, and at the same time we try to isolate, to find those rare people who are only alcoholics and don’t have a history of depression or multidrugs use. Then we can study pure alcoholism.”

Whatever Berman’s data suggest about gender differences in alcoholism, it is, she acknowledges, a very small piece of a large, unwieldy puzzle. Why do some people become addicted to alcohol in the first place? “Who knows” exactly why, she says. “There are lots and lots of reasons.”

“The subjects are all individuals,” says Ruiz. “Alcoholics are people and everybody has a different story. They have different genetics and grew up in different environments. Gender is just one piece of that.”

The Addiction Puzzle

This Series

Also in

The Addiction Puzzle

-

November 18, 2013

The Addiction Puzzle, Part 1: An Overdose Lifeline

-

November 19, 2013

The Addiction Puzzle, Part 2: Could ADHD Meds Promote Future Cocaine Use?

-

November 20, 2013

The Addiction Puzzle, Part 3: The Search for the Alcohol Trigger

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.