Is Obesity a Disease?

American doctors vote yes, BU profs weigh in on debate

The nation’s top doc group has voted to classify obesity as a disease.

An overdue bow to science or a clever dodge of the real problem? The American Medical Association’s decision Tuesday to classify obesity as a disease left the weight of expert opinion, so to speak, unsettled.

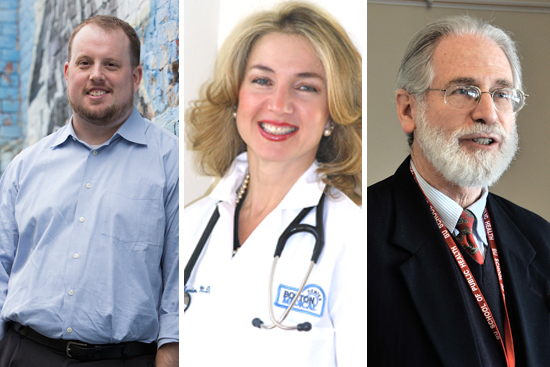

“Long time coming—I have been fighting for this for over 20 years,” says Caroline Apovian, a School of Medicine professor of medicine and pediatrics and director of the Nutrition and Weight Management Center at Boston Medical Center. Obesity researcher Daniel Miller is more circumspect. The School of Social Work assistant professor fears that the decision “will prompt people to further identify obesity as a purely medical problem, and one that is best treated by pharmaceuticals or surgery,” leaving what he calls the root causes—social and environmental influences—in the dust. Miller agrees, however, that if the decision “means access to treatment for some who otherwise might not be able to get it, that is obviously a good thing.”

Then there’s the wait-and-see school. Whether the AMA made the right call depends on whether it “will reduce the number of obese Americans and the gravity of their obesity,” says Alan Sager, a School of Public Health professor of health policy and management. And take-two-pills-and-call-me-in-the-morning hasn’t worked to date to stem the wave of weight, he says: “Doctors have never been the most powerful actors in combating obesity,” which has mushroomed because of such things as the cost and distribution of good foods and changes in exercise patterns.

Apovian says the disease designation is justified by research showing that weight gain in animals correlates to damage in the gut-to-brain signaling system. “The body does not recognize how much fat is being stored,” she says. “Therefore, you do not feel full, and keep eating.”

The vote by the AMA, the country’s premier doctor group, fired up numerous questions, ranging from the best way to treat this newly defined disease to the implications for insurance and social attitudes toward the overweight. The newest disease affects more than one-third of Americans and costs $147 billion a year in medical bills. The AMA’s verdict—which contravened the recommendation of its own study committee—cited a need to destigmatize obesity, which some doctors say is not subject solely to people’s control, and the fact that obesity has some effects of disease, such as interfering with the body’s function.

Opponents counter that a disease must be diagnosable, and the diagnostic tool for identifying obesity, body mass index, is unrealistic and unreliable. Professional athletes have clocked in as overweight under versions of the BMI, because muscle weighs more than fat.

Critics contend also that obesity is a risk factor for diseases like diabetes or heart ailments, rather than a disease itself. They predict more runaway medical costs if overweight people now turn to surgery and drugs rather than to diet and exercise.

If carrying excess pounds is a disease, should eating better and physical activity be considered best-practice treatment? Apovian says no, because our body chemistry often renders those tactics alone futile: “The body thinks it is starving and is going to get you back to that set point by making you very, very hungry. This is the essence for why it is a disease.”

On this point, Miller agrees with Apovian, saying individual responsibility is one strand in a complex causation web that can include environmental factors well beyond a person’s control. Poor neighborhoods, for example, are often nutrition “deserts,” with few stores that sell healthful food. For that reason, Apovian argues, the government should classify such neighborhoods as medically underserved, a designation now given to areas with a shortage of health care providers. “Bad food, hopefully, in the next few years will be seen as poison,” she says. “Just like we did with tobacco.”

Sager doubts that such a designation will be made. He points out that free-market advocates have blocked government action on helping underserved populations, and their philosophy is sure to extend to government promotion of stores carrying healthful foods. Also, he says, legally speaking, “no one is obliged to do anything different because the AMA has voted to rename obesity a disease.”

Apovian believes the decision actually will aid President Obama’s goal of “bending the cost curve” in medicine. In some cases, she says, insurance companies already cover bariatric (stomach-reducing) surgery; if the AMA’s vote pushes them to pay for diet and exercise programs to prevent obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, it will save money in the future treating those problems. Sager predicts “a modest effect” in expanded insurance coverage from the AMA decision.

Should the new definition of obesity influence attitudes toward the obese? For example, nonobese travelers applauded a requirement by some airlines that obese passengers purchase two seats instead of squeezing into one seat and overwhelming the person next to them. If obesity is a disease, doesn’t that policy become discrimination?

“Yes, absolutely. Make the seats bigger, for God’s sake,” says Apovian.

Air Canada has an intriguing third way. It gives a free second seat to obese fliers who present a doctor’s note to the airline.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.