Tale of Passion and Deceit Opens CFA Fringe Festival

Jonathan Dove’s timely, tangled story of love and intrigue

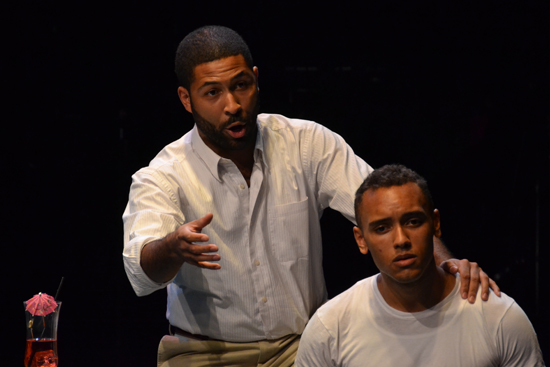

Benjamin Taylor (CFA’14) (left) and Jordan Weatherston (CFA’14) in the one-act opera Siren Song, which opens the CFA 17th annual Fringe Festival at the BU Theatre. Photos by Oshin Gregorian

The tangled story of a sailor who falls deeply in love through a passionate exchange of letters with a lonely young woman—or so he believes—opens the College of Fine Arts 17th Fall Fringe Festival tonight. Even though composed before the existence of online matchmaking, British composer Jonathan Dove’s one-act opera Siren Song “seems timely in this age where we constantly hear about false online identities and trickery,” says Opera Institute director William Lumpkin.

The opera is based on a novel of the same name by Gordon Honeycombe, which was in turn inspired by the real life story of a young Royal Navy sailor. Sung in English, Siren Song is “serene and captivating,” says Lumpkin, a CFA associate professor of music and acting director of the Opera Institute. In the CFA production of the opera, which premiered in 1994, the 10-piece orchestra will include a heavy use of percussion, harp, and piano, along with a flute, an oboe, a clarinet, a horn, a violin, a cello, and a bass. Stage direction of the six-member cast, four in double roles, is by Jim Petosa, director of the School of Theatre. The libretto was written by Nick Dear.

“I fell in love with Jonathan’s opera Flight when I had the pleasure of conducting the American premiere, and it has been a delight to come back to his earlier opera Siren Song,” Lumpkin says.

The Fringe Festival is a collaboration among CFA’s School of Music, School of Theatre, and Opera Institute. The festival’s mission is to produce significant new or rarely performed opera and theater works and bring together performers and audiences in unique theatrical settings. After Siren Song, which is being performed October 4 to 6, this year’s program continues with Nico Muhly’s two-act opera Dark Sisters, about a woman’s attempt to escape the polygamous fundamentalist fringe of the Mormon Church. It runs from October 11 to 13, with Allison Voth, a CFA associate professor and Opera Institute principal coach, as music director and David Gately as guest stage director. The festival concludes with Sam Shepard’s one-act play Back Bog Beast Bait, in which a two-headed “pig beast” terrorizes the Louisiana countryside and must be stopped. Directed by Michael Hammond, a CFA assistant professor of acting, it will be performed October 22 to 24 and October 26 and 27. All performances are at the Boston University Theatre Lane-Comley Studio 210.

Born in London in 1959, Dove has composed choral works, orchestral and chamber music, and scores for plays and films in addition to operas. BU Today asked Dove, a newcomer to the Fringe Festival, about what drew him to the Siren Song story, why it resonates with today’s audiences, and what can be done to increase opera’s appeal among younger audiences.

BU Today: How often are your works performed in the United States, and have you found American opera audiences distinctive or different?

Dove: My opera Flight has had a number of productions in the United States. The Adventures of Pinocchio was staged by Minnesota Opera, and Tobias and the Angel by Opera Vivente in Baltimore. In general, I have found American opera audiences to be warm and responsive.

What drew you to Honeycombe’s story? Are there certain elements that make a story “operatic”?

In fact, the story isn’t Gordon Honeycombe’s, although he wrote the book. It is a true story, told to Honeycombe by the detective on the case. When I read a review of his book, it seemed immediately to be an opera plot—although at first I didn’t imagine that I would end up writing the opera myself. There are no rules about what makes a story operatic: certain stories spark something in the imaginations of certain composers. In this story, I think it was the mixture of love and intrigue that initially caught my imagination. In fact, the story is, in a way, a celebration of the power of the imagination.

In what ways are audience members likely to see themselves in the character of the sailor Davey?

An innocent, honest, and trusting person will empathize with Davey. I think many in the audience might feel that Davey was easily duped, and that they themselves would not have been fooled. But stories of this kind are surprisingly common. A lonely person eager to fall in love can create a rich and fascinating picture of the person they fall in love with, based on sometimes slender information: their imagination fills in the missing details. Which of us has not, at some time, discovered that we were mistaken about the person we were in love with? In other words, we imagined the person we fell in love with, our fantasy created someone for us to love, but the real person was quite different.

What are the ageless themes of Siren Song and what are the more urgent, modern ones?

The connection between love and imagination, or love and fantasy, is timeless. I have read accounts of experiences similar to Davey’s involving internet chat rooms. Someone searching for love can be vulnerable to deception, and as we know, people online are not always who they seem to be. So this is absolutely a modern issue.

Tell us about your use of Eastern music in the score and what it’s meant to evoke.

The opera is scored for a small chamber ensemble of 10 players. They don’t actually play gamelan instruments, but in a couple of scenes they evoke the sound of Indonesian gamelan music to suggest the exotic locations to which Jonathan takes Davey: the Raffles Hotel in Singapore and a beach in Bali.

I’ve read that you are passionate about introducing new audiences to opera. Would Siren Song be a compelling introduction for opera novices?

I think Siren Song is an ideal first opera. Especially for an English speaker, as the opera is in English. It’s not too long, around 70 minutes, and it’s made of quite short, contrasting scenes. There isn’t a great deal of what I would call extreme singing—something opera lovers appreciate, but which can be alarming for a first-time viewer. The character of Davey, in particular, the central role, for the most part does not sing high, sustained lines like Puccini’s. His role begins near to speech, and only gradually develops lyric intensity, so that an ordinary theatergoer can be drawn into his experience. Best of all, the true story takes place very near to the present day (although a little before emails and cell phones), and so is easily recognizable to a modern audience. It begins on an aircraft carrier, and at one point someone buys a microwave—and sings about it.

Are there common misconceptions about opera that keep young people away from it?

Young people often imagine that operas are long and boring, sung in a foreign language by fat people wearing wigs or Viking helmets. But if they have the chance to experience an opera singer up close, singing in their own language, and feel the intensity of the sound produced without amplification, they are likely to be enthralled, especially if it’s a story they can follow and find interesting.

How do you envision the evolution and reinvention of opera? Are there stories you’d like to compose for, and stage, in fresh and innovative ways and venues?

Opera has already traveled a long way. Following in the footsteps of composers such as Benjamin Britten, I have already written operas for enormous numbers of amateur performers to sing and play in unconventional spaces (one of them began in a cathedral and ended up in a shopping mall, with some 600 performers taking part). I have written operas specifically for television, operas with piano accompaniment to be played in country houses, church operas, site-specific operas, chamber operas, and operas for all the family. There are no limits to what opera might become. I recently saw an opera in which live singers interacted with characters in a 3-D film. I have been working for a while on an ambitious project: to write a community opera that will be performed across three continents, using the internet and big screens so that performers can sing to each other across the world.

Performances of Siren Song are tonight, Friday, October 4, at 7:30 p.m., Saturday, October 5, at 2 and 7:30 p.m., and Sunday, October 6, at 2 p.m., at the BU Theatre Lane-Comley Studio 210, 264 Huntington Ave. Tickets are $7 general admission; one free ticket with BU ID, subject to availability. Purchase tickets here or call 617-933-8600. To get to the BU Theatre by public transportation, take an MBTA Green Line E trolley to Symphony or the Orange Line to Massachusetts Avenue.

Find a complete list of Fringe Festival events here.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.