Carpet Seller, Storyteller

BU student publishes memoir of life under the Taliban

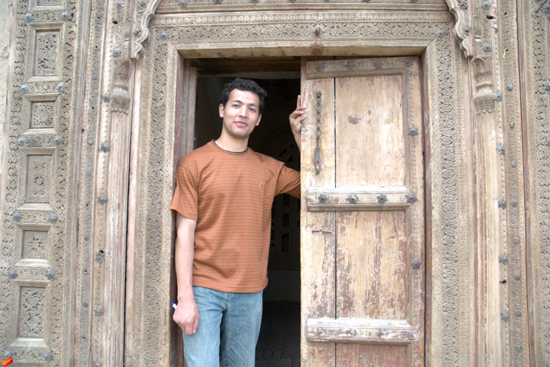

A Fort of Nine Towers, a new memoir by Qais Akbar Omar (GRS’16), recounts his life growing up in Afghanistan. Photo by Jason Burke

In Kabul, Qais Akbar Omar is known for selling quality carpets through his family business, which has endured through Afghanistan’s long years of strife. In the United States, he is becoming increasingly known as the author of the critically acclaimed memoir A Fort of Nine Towers: An Afghan Family Story (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), a captivating, elegantly written book that includes, as a Washington Post critic writes, moments “when the grief becomes almost too difficult to bear.” Omar’s book chronicles the hardships of his family from the end of the Soviet occupation to Taliban rule to the US invasion in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

Fleeing the violence of their beloved city of Kabul, they set out on an epic journey that saw them barrel over the Khyber Pass in an old Volga auto, camp in a cave inside one of the heads of the towering Bamiyan Buddhas, and huddle with their Kuchi nomad relatives in goat-hair tents. Their reverence for life and beauty survives despite days spent cowering under rocket fire and the humiliations of life under the Taliban. Omar (GRS’16) learns to weave carpets, then stories.

At the conclusion of his first semester in BU’s Creative Writing Program, Omar, who had previously collaborated with playwright Stephen Landrigan on 2012’s Shakespeare in Kabul, sat down with BU Today over dinner at a local Afghan restaurant. He spoke of his surprise at the growing media coverage of A Fort of Nine Towers, the book’s long, painful gestation, and adjusting to life away from the warmth, laughter, and most of all, the meals shared with his family.

BU Today: What made you begin writing down your experiences?

Omar: Foreigners who came into Afghanistan asked me what it was like during the years of Taliban, and before that, the civil war. The more I talked about it, the more I felt good, like I had to get these stories out of me. When I talked about the past, I did not have nightmares anymore. I made good friends with Americans and Canadians, and when I told my stories they told me it’s like therapy. We don’t have psychiatrists in Afghanistan. Then several friends said I should just go ahead and write the stories down.

Why did you write the book in English, which you’d only recently learned, rather than your native language?

I tried to do that in Dari; it was just too painful because I have a lot of sentimental attachment to Dari and Pashto. So at first I thought, I just can’t do this.

What changed your mind?

I decided to write my story down two years later, in 2005. I saw something on TV that reminded me of the past—some suicide bombers or something, just a very horrible scene. So I went to my bedroom, which often happens when I see something horrible on the TV—whether it’s Afghanistan or Iraq or any other country—I either have to change the channel or get out of the room because it reminds me of the past. It’s just too painful for me. It brings a lot of memories back.

The writing was a kind of emotional marathon for you. Can you describe the process?

I went to my bedroom and I just started writing something that brought the memories back. I wrote about 10 pages, and then it came like gush, and I couldn’t stop it. For two months I hardly walked out of my room. I only came out to use the bathroom or the kitchen to eat something. I just stayed in the room and wrote and wrote and wrote. After two months I had written over 700 pages. It was a very painful process. Sometimes I cried; sometimes I laughed. When you go through all these things in life, you go through them one by one. But when you write them, it’s all coming all at once at you, and you have to live through them. You literally feel the pain on your back from when you were beaten up by a Taliban.

How did your family react to this?

I told my mom, “I just have to get this all out of me,” and she said, “You are very brave. Whatever helps, do it.” My mother would come down the stairs at two in the morning and sit on the edge of my bed and ask, “What are you writing now?” I would tell her, “Do you remember that scene when my father and I came back from being held by the Taliban and you guys were busy with our funeral?” So she would say, “Do you remember when your cousin was trying to get out your kites and marbles and then you said, ‘Don’t touch them!’ But do you know that they were doing it to help you?” She would come up with those funny parts to help me.

So your mother inspired the lighter moments in the book?

She would remind me that it is not just dark stuff. Normally you just remember all the dark stuff when you try to write. We went through such hard times, but we had some really happy moments. Like when we got to the Bamiyan Buddha caves and my father said, “We can live here,” and my mom said, “No, because what if the kids fall,” but we had those begging eyes, so my father said, “Okay, but I have two rules: Everybody should look after each other, and when you climb the stairs you have to be very careful.” My mother reminded me how she’d give me a plate of kebab to bring to the weird guy, the monk, in another cave. And I would say, “Oh yeah, actually I remember.” So I would write about things like that, and that brought me back into a good mood. And after seven or eight hours writing about happy things, I’d go back in the dark, and she’d come back and again she would tell me some happy parts. Then that’s how the whole process went.

Had you read any books in English before you wrote yours?

I hadn’t read anything in English until 2001. When the Americans came to Afghanistan after 9/11 and I had my carpet factory, I used to make about $300 a month with my whole factory. I had friends who would make $100 for just a day of being a translator for the American military. So I thought, I’ve got to learn this language and make some more money. So I went out and bought some English books and started teaching myself. It took me six months to learn enough to get a job.

What were the first English language books you read?

Beginner books—“This is a pen,” That’s a cat,” That’s a woman,” stuff like that. As soon as I started reading those, I started reading a lot of news, and then I moved on to novels. At the beginning it was just whatever I could find. Back then it was not very easy to find books in Kabul, so I would go and read the manual for a washing machine. And then I would tell my mom, “You have to use the washing machine like this,” and she’d bang me on the head with the manual and say, “I’ve been using this washing machine for 18 years and now you’re telling me how to use it? Shut up!” So I would read anything. And then, slowly, we had a lot of books coming to Afghanistan by these foreigners. The first one I read was by Alexander McCall Smith, about the Botswana ladies’ detective agency. Now I read at least three English books a month.

How did you find a publisher?

I just sent some of my foreign friends the whole thing through email or gave them a flash drive. The reaction I got from all of them, whether they are French, English, Italian, or Canadian, was, “You have to publish this! If you don’t publish this then the world is not going to know what you went through.” At first I thought, this is too personal. I cannot share this with the world. It’s too much exposure. But I kept getting emails saying, “You have to publish this.” Finally I said, “Maybe people need to know.” So I went to talk to my parents about it, and they encouraged me. They said, “How can the world not know what Afghanistan has been through?” So then I had to convince my cousins, my uncles, and aunts. And they all said the same thing. I asked my friend from Boston, my Shakespeare in Kabul coauthor Stephen Landrigan, if he could help me. He went to several publishing houses, which said no. Then several friends told me that I should find an agent, so I looked for one online. Two weeks after I found an agent in New York, Simon & Schuster said they would publish it for a huge amount of money.

So there was a bidding war?

Yes! My agent called to say, “You have to stay up until three in the morning because I have three publishers who are all willing to publish it.” All of them were nice women saying wonderful things about my book. I chose Farrar, Straus & Giroux because I heard once they are a well-established and very prestigious publishing house, and they will work hard to sell the book.

How close is the book to the original 700 pages?

I was told I had to cut some parts, because they were too graphic and too hard for women to read. I cut it down to 400 pages.

How have your English-speaking Afghan friends reacted to the book?

Everyone in Afghanistan went through the same thing, sometimes a lot worse. Yesterday I heard from a couple of Afghan friends in America who lived most of their lives in Afghanistan, and they said, “Qais, you are so brave.” Each page reminded them of something that they went through, so now they are writing their memories. I think every Afghan who has lived through the years of the Taliban and the civil war has a story like mine to tell.

Is it strange for you to read newspaper articles about yourself and listen to yourself on the radio?

Yes, it is, because I was not expecting any of this. It’s all a surprise every day when I get all of these big reviews. My publicist tells me that I’ll have a review in Oprah magazine, for example. I don’t know what Oprah magazine is. Then I go online and find out that it’s a big deal. Then I hear that I’ll have a review by the Washington Post or the New York Times. Every day is such a big surprise. And I wrote this mostly to get rid of those nightmares that haunted me.

Your gentle, straightforward writing style has drawn much critical praise. Did that style come naturally?

I don’t think I have a writing style. Afghans, in general, are very good storytellers. I try to just tell my story like it happened. But you have to focus on the details, because details are the beauty of a story. When I read what I wrote, I noticed that the early parts of the book sound like it has been written from the point of view of a child. And suddenly I could see the whole pattern in my story, that I’m actually growing up throughout the story. It just happened naturally; it was not like I intended that. But I decided it’s a good thing, so I just kept it that way.

Do you attribute your literary gift to your parents?

My mother is a very good storyteller. There were times when we would stay in the basement for weeks because there were thousands of rockets raining over Kabul every day. So as the rockets were landing all around us, my mother would distract us from the sound and all the horrible things by telling us a very good story that could last from one hour to one year. So I think that had a lot to do with it: living in the basement with my family or on the roof for weeks. And my father forced us to read books. Mostly poetry by Rumi or just novels, and then he would ask us questions about what we learned from the story.

What do you think will happen after the Americans leave Afghanistan?

Every conversation I have with my parents on Skype, they ask me the same question over and over again: “What will happen after 2014? What do Americans think? What are they talking about there?” And actually, in America nobody talks about it. Nobody cares much, because America is so big and they just have so many other things to do. So I just tell them I don’t know. But one thing we do know is that we had five years of civil war after the Soviets left Afghanistan, after the Soviets were defeated by factions funded by the Americans and Pakistan. And then we had the Taliban. Now those factions are back. They are basically running the country. Then we have the local warlords, and the drug lords, and they all have more money and more weapons than ever. Will we have another civil war after 2014? We don’t know. Will we get along with each other? Who knows? Maybe, maybe not. But we know we cannot afford to have another civil war. We lost so many people. Afghans are tired of war.

How does having witnessed so much violence change you as a person?

You have to find a way to shield yourself so you can get on with life. Otherwise you will be depressed the whole time and you won’t walk out of your room. And we are not that weak to go and hang ourselves from the ceiling fan. You have to find a way to live with it. Today is a new day; you’ll probably have some adventures today or you will make some money. You just focus on something positive in your life. You make some good money and then you come home with three kilos of lamb and then you have kebab with your family and listen to music and make some jokes and tell stories or sit around the table and recite poetry and have a poetry contest. So you just focus on those positive things, the very few we have in Afghanistan. Otherwise you can’t live; it’s just impossible.

How are your BU studies going?

I really enjoy all my classes at BU. I’ve come across writers like Emerson, Thoreau, Dreiser, and Mark Twain. Huckleberry Finn is the best.

Was the transition to life here strange for you?

Very much, yes. The first few months I came here it was not easy for me to be away from my family because I don’t cook anything. I couldn’t cook anything except for eggs. And I can’t go on eating eggs for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Is it safe for you to return to Afghanistan?

I have to stay away for the time being because of the book. Even though I didn’t talk specifically about warlords or the Taliban, I wrote about how the regime changed our families and our lives. That’s very vivid throughout the book. So it’s probably not a good idea for me go there now.

Learn more about Qais Akbar Omar’s story of growing up in Afghanistan here. Listen to an interview he recently gave to WBUR, Boston University’s NPR news station, here.

A version of this story also appeared in the fall 2013 edition of Arts & Sciences.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.