In the Running: 1897 to 2014

BU grads who made Boston Marathon history

The first Americans to compete in the modern Olympics were mostly members of the Boston Athletic Association, including BU student Tom Burke (LAW 1897) (standing, left). They brought back from Athens the idea of staging a “Marathon race” in Boston.

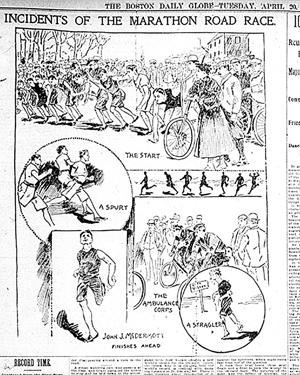

Like a Wild West gunslinger, he dragged his boot heel across the dirt road, making a line—18 men crouched behind it and waited for his signal. Lacking a pistol, Tom Burke simply shouted, “Go!”

It was the first Boston Marathon, and Burke (LAW 1897) was the race’s first official starter—as well as its cofounder. A former BU track star and Olympian, he was the first of several Boston University alumni to play a key part in the history of the nation’s oldest annual marathon. As the BU community comes together to root for University runners in Monday’s race—many who will be running in honor of Lu Lingzi (GRS’13), killed in last year’s bombings—we take a glimpse back at some of the Terriers who have stood out over more than a century of this beloved Boston event.

The starter

When he was a “tall skinny kid” walking with a crutch because of rheumatism, Thomas Edmund Burke “looked anything but a runner.” So recalled a sportswriter who grew up with him in the crowded tenements of Boston’s West End. Doctors thought Burke would need that crutch for life. But by his late teens, the undertaker’s son was winning regional and then national track championships at the quarter-mile distance. At age 20, he was picked to compete in the first modern Olympics, at Athens in April 1896.

To make the steamship journey to Greece and back, Burke had to take a six-week leave of absence from his law studies. “I shall wear the colors of BU in these games,” he wrote in a letter to the School of Law, “and hope to uphold the reputation of the University.” True to his promise, Burke won gold medals in the 400-meter and 100-meter events.

While at the Olympics, Burke and the rest of the contingent from the Boston Athletic Association (who made up the bulk of the American delegation) witnessed the world’s first-ever “Marathon race.” This 25-mile run from the plains of Marathon to the city of Athens celebrated the legend of Pheidippides, the Ancient Greek messenger said to have run that route to deliver news of the Greek victory over the Persians. Burke and BAA coach John Graham were especially impressed.

Back in Boston, the BAA began planning a similar foot race, and Burke and Graham were the event’s two prime movers, according to John Hanc, author of The B.A.A. at 125: The Official History of the Boston Athletic Association, 1887-2012 (Sports Publishing, 2013). Their efforts succeeded about a year later, on April 19, 1897 (Patriots’ Day). That’s when Burke scratched that line in the dirt on a country road in Ashland, Mass., and with the word “Go,” sent 18 amateur athletes on their way to Boston—and into history.

Eventually, the size of the field would grow, the starting line would move to Hopkinton, and the race’s conditions would change dramatically—runners in those early years contended with muddy roads on rainy days, clouds of dust on dry days, and armies of bicycles, horses, and clattering automobiles regardless of the weather. Sometimes the race’s progress was interrupted by funeral processions or freight trains. But the Boston Marathon was here to stay.

Burke later worked as a lawyer, a track coach, and a journalist, as Michael Quinlin (COM’92) recounts in Irish Boston: A Lively Look at Boston’s Colorful Irish Past (Globe Pequot, 2004), and at age 43 he became America’s oldest pilot in World War I.

The Reverend

Clarence DeMar (SED’34) won the Boston Marathon seven times, earning the nickname “Mr. DeMarathon.” After his first win in 1911, he took a long break from serious competition—partly because doctors told him he had a bad heart, partly because the devout Baptist feared the pride-inflating spotlight. But he returned for back-to-back wins in 1922 and 1923. His 1922 time of 2:18:10 stands as the course record for the old distance of 24.5 miles. In 1924, the BAA extended it to the now-standard 26.2 miles (first used in the 1908 Olympics at London). But the extra mile-plus didn’t faze DeMar—he won Boston that April, and that summer took Olympic bronze at Paris.

What did faze DeMar were the spectators who got too close, whether by standing in the road or driving on it: with the exception of the final mile in Boston, no ropes held the crowds back and no barriers blocked automobile traffic. The surly Yankee socked a few fans who got in his face, slugged a motorist who’d veered into his path, and even a kicked a dog that was nipping at his heels.

DeMar won Boston again in 1927 and 1928, along with marathons in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. He won his last Boston Marathon in 1930, at age 41, and kept running the race until 1954, when he was 65.

A printer by trade and a Baptist minister in his spare time, DeMar traveled a long journey to earn his master’s degree at BU’s School of Education. Not only in the sense that he spent decades supporting first his mother and five siblings, and then (after marrying at age 40) his wife and five children, by working in the Dickensian newspaper printing shops of his time—hot, dark cellars, where molten lead pots spewed poisonous fumes, according to Ashland journalist Steve Flynn. But also quite literally—DeMar traveled 90 miles to Boston each week from his home in Keene, N.H., walking and hitchhiking to his SED classes and student teaching placements. Four hours to BU, four hours back. DeMar often braved subzero temperatures, suspicious cops, and skunks to complete this biweekly odyssey.

“On the whole I was sorry when my points were earned and I had my Master’s degree in June, 1934,” DeMar wrote in his memoir, “for the night walks had been invigorating and combined [with] the mental stimulus of study made life very enjoyable.”

“The Younger”

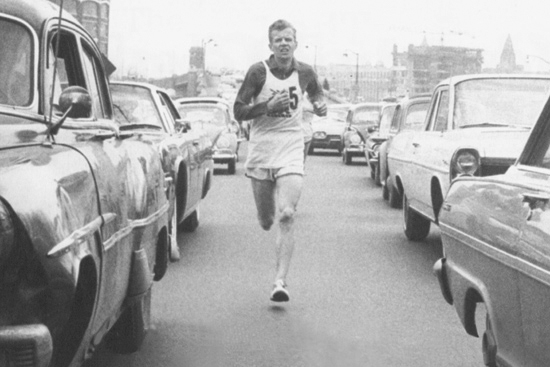

They called him Johnny Kelley “the Younger” to distinguish him from fellow marathoner John A. Kelley (aka Johnny Kelley “the Elder”). But John J. Kelley (SED’56) had another nickname in the 1950s: “America’s Only Hope.” Runners from Finland, Japan, and other distant shores had dominated the Boston Marathon for more than a decade. Indeed, no American had won the Patriots’ Day classic since the war.

Kelley was at BU on a track scholarship when he began training for the marathon. This was an unconventional activity for a college student then. Since the sport’s invention, marathoners had always been bricklayers, plumbers, printers—blue-collar laborers. Kelley knew something about hard work—he lugged boxes in a jewelry store basement and served up burgers in a fast-paced cafeteria kitchen to put himself through BU—but he was still a college athlete, which for a runner of that era meant a sprinter. But despite his considerable prowess on the track, Kelley was drawn to the road—appropriate for a Kerouac fan. In particular, Kelley was drawn to the great road race that passed practically under his dorm room window at Myles Standish Hall.

In 1953, Kelley completed his first Boston Marathon, finishing fifth, with a time of 2:28:19. That’s when local fans pinned their hopes on the kid from BU. In 1956, he came in second, losing to a Finn by 19 seconds. At last, in 1957, Kelley passed former champion Veikko Karvonen on the Newton hills to take the lead. Still in front at Kenmore Square, Kelley felt “a qualified ‘Whew!’ The race was almost done and yet that crucial mile remained,” he told his school alumni magazine @SED years later. “Those thousands of fans, [including] BU students—many of them my friends from Myles Standish dorm or classes—I couldn’t let them down at this penultimate moment!” Kelley held on to win in 2:20:05.

All told, Kelley ran 34 Boston marathons, finishing first among Americans eight times. He also won eight straight Yonkers Marathons and competed in the Olympics twice. What’s more, by his example he broke open marathoning as a sport that welcomed college students and graduates—such as his mentees and fellow Connecticut natives Amby Burfoot (who won Boston in 1968) and Bill Rodgers (who won in 1975, 1978, 1979, and 1980).

The duo

Nearly every year since 1977, Dick Hoyt has run the Boston Marathon pushing his son, Rick Hoyt (SED’93), in a customized wheelchair. Together, the two have competed in more than 1,000 races, including triathlons (for the swimming portion, Rick rides in a small boat).

Rick has cerebral palsy and quadriplegia, but that didn’t stop him from attending public schools and then graduating from Boston University. He communicates with a computer, typing by moving his head. (His first words, at age 10, in 1972: “Go Bruins.” The Bs won the Stanley Cup that year.)

Team Hoyt was ready to retire in 2013. But after being stopped a mile from the finish line when the bombs went off in Boston last year, they decided to run the race one last time, next Monday. “We will get across this year,” 73-year-old Dick told Runner’s World. “It’s going to be very emotional.”

Honorable mention

Although not alumni, a few other key figures from the marathon’s past had strong BU connections. Dudley Allen Sargent, founder of the Sargent College of Physical Training—today the BU College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College—was a father of the modern fitness movement that resulted in today’s Boston Marathon.

George V. Brown, BU’s first athletic director, was the marathon’s manager and starter—unlike Burke, he used a pistol—from the early 1900s until his death in 1937. More than that, Brown kept the BAA and the marathon alive after the Depression-era collapse of the once-affluent gentleman’s club. After George’s death, his son, Walter Brown (as in Walter Brown Arena), took over as starter. The younger Brown also founded the Beanpot and the Boston Celtics.

In his memoirs, longtime Boston Marathon manager Jock Semple wrote that Walter Brown got him a carpentry job at BU after World War II. Semple also hoped to attend Sargent College for physical therapy, and some of his obituaries later stated that he did. However, the registrar has no records of his attendance, and BU’s employment records don’t extend that far back. What is certain is that Semple (who also became the trainer for the Bruins and Celtics) was a mentor to Kelley, the BU student who finally chose marathoning over sprinting and won the big Boston race in 1957.

Patrick L. Kennedy (COM’04) is writing a book about the Boston Marathon, focusing on his relative “Bricklayer Bill” Kennedy, who won the race in 1917. He can be reached at plk@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.