Darwin and the Bible Meet in Creation Stories Class

A classicist on mythical and scientific accounts of how the world began

Class by class, lecture by lecture, question asked by question answered, an education is built. This is one of a series of articles about visits to one class, on one day, in search of those building blocks at BU.

Charles Darwin didn’t wear a toga, genuflect to the pantheon of ancient gods, or render anything unto Caesar. So what is the explicator of evolution doing in a classical studies class? For that matter, why do Stephen Scully’s students ponder the Big Bang as well as Darwin?

Because evolution and the Big Bang—like more ancient beginning-of-the-world accounts, in Genesis and elsewhere—are Creation Stories, and that is the name of Scully’s class. And for all their obvious differences, these stories, be they products of modern science or fables from the fog of antiquity, have more in common than you might think, says Scully, a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor and chair of classical studies.

The similarities (and differences) came out in a recent class session devoted to the final chapter of Darwin’s epochal On the Origin of Species, where the naturalist defends the theory of evolution against religious critics. Some of his words—“There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one…”—deliberately echo Genesis; Darwin wrote them in his book’s second edition, apparently addressing blowback from believers about the first edition, Scully tells the class.

Darwin may have borrowed the language of scripture, but “is the theory inimical to a religious view?” Scully quizzes his students. “He’s saying no, but…does this get him off the hook?”

“It all depends on how involved you take faith to be in the workings of everyday life,” Christian Walls (CAS’16) says. An evolutionist might think a divine Creator ignited the process, but Darwin implies that natural processes took over from there in developing what we see around us, rather than recurring divine intervention in the world, he notes.

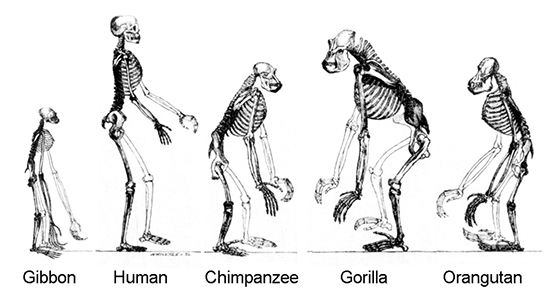

Darwinism also raises questions about the idea that we are special creatures, created in God’s image. “There’s no reason to think that we are in a privileged position not to become extinct,” Scully tells the students, one of whom suggests the Bible doesn’t refute that view; the story of the Flood involved a human extinction. Scully agrees but says evolution levels the field between us and other species. “We humans are not, from Darwin’s point of view, special. We are in process.…We might be like the early form of the horse,” a fox-sized animal quite different from its modern descendant.

Demonstrating that these arguments were as volatile 150 years ago as they are today, Scully distributes a caricature from the scientist’s lifetime, with Darwin’s head atop an ape’s body.

Scully conceived the course “purely out of curiosity,” he says, while writing his recent book about Hesiod’s “Theogony,” an eighth century BCE poem about the beginning of the world, which is on his syllabus. Other creation accounts the class ponders include those of the Roman philosopher-poet Lucretius (who suggested physical principles and not gods operated the universe) and intelligent design.

“Every discipline talks about creations, they all have them, and I just became interested in how they talk about them,” Scully says. “What is the language they use, what are the questions they ask? What are the questions they don’t ask?”

Learning the answers meant the teacher had to become a pupil of disciplines beyond his own. Boning up on the Big Bang, for example, reinforced his view that creation narratives have commonalities: while religious stories are faith-based, science must make temporary, if educated, leaps of faith in formulating hypotheses, he says. “Many aspects of the Big Bang were constructed with hypothetical constructs, mathematically, which over time have been proven to be true” under empirical observation.

For all the similarities of creation accounts, the class’ key takeaway is the different goals of science and religion in telling stories. The former “tends to talk about how things happen as opposed to why things happen,” Scully says, leaving the whys to religion.

A class mingling science and faith can expect to draw pupils of both. For biology major Jordyn Beesmer (CAS’18), comparing “the science of creation to the myth of creation” exposed her to the similarities, at least the metaphorical ones. “A common theme in a few of the stories that we’ve read was violence in the beginning of the stories,” she says. “Obviously, the Big Bang is a very violent happening.”

Classical studies major Walls agrees. The course has taught him that “how ancient peoples would think of origin stories really hasn’t differed very much from the origin stories that we’ve created today.”

This Series

Also in

One Class, One Day

-

November 30, 2018

Breaking Bad Director Gives CAS Class the Inside Dope

-

October 31, 2018

Trump and the Press: We’ve Been Here Before

-

August 3, 2018

A Scholarly Take on Superheroes

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.