Why Harper Lee’s Watchman Matters

CAS prof on the novel, the South, and the humanities

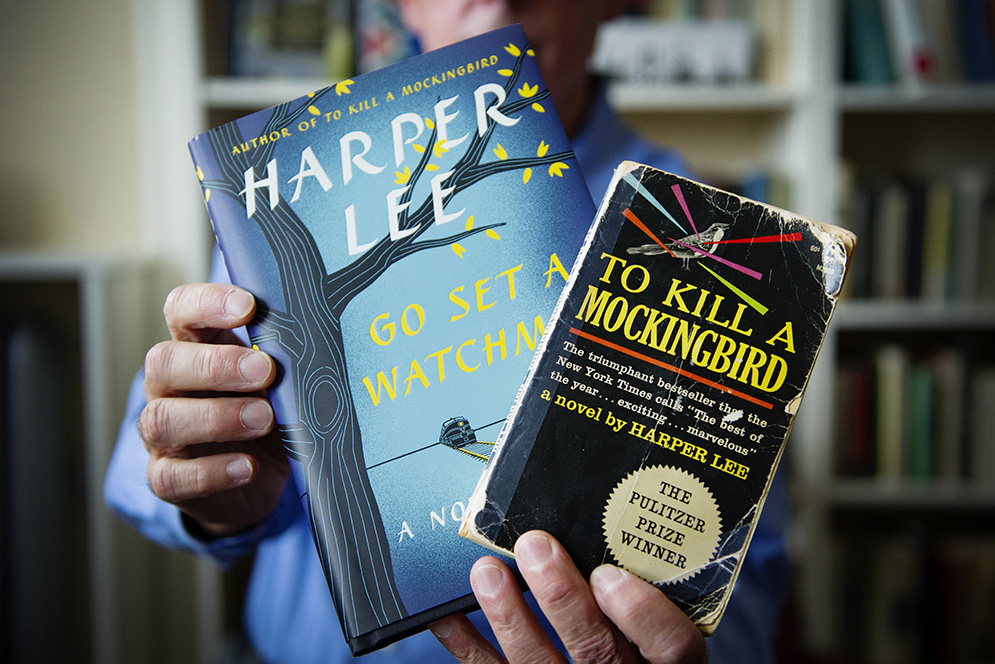

John Matthews, a scholar of the literature of the American South, views Harper Lee’s newly published novel, Go Set a Watchman, together with her 1960 classic, To Kill a Mockingbird, as a CAT scan of the South and the American psyche. “You have to interpret it,” he says. “The South, the individuals in it, it’s not one thing.” Photos by Jackie Ricciardi

The intense discussion this summer about the newly published Harper Lee novel, Go Set a Watchman—and the remembrances of Lee’s widely admired, coming-of-age classic, To Kill a Mockingbird (1960)—can be viewed, perhaps, as a validation of the humanities’ task: “To revisit things, to unsettle, to think about the things you thought you knew,” says John T. Matthews, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English who has devoted his life to teaching and studying American literature. “I think this book does invite that.”

HarperCollins published Watchman on July 14, some 60 years after Lee wrote it, amid concerns over whether the author, who is 89 and in frail health, fully supported its publication. Soaring to the top of the bestseller lists, the novel sold more than 1.1 million copies in the first week.

In a front page review in the New York Times, Michiko Kakutani recalled the Atticus Finch who was “the moral conscience” of Mockingbird, the white Southern lawyer defending an innocent black man against rape charges in Alabama in the 1930s. “Shockingly,” she wrote in her review, the Atticus Finch of Watchman “is a racist who once attended a Klan meeting, who says things like ‘The Negroes down here are still in their childhood as a people.’”

Other readers, however, saw Watchman’s Atticus through a different lens. Writing in the New Yorker, Dale Russakoff, who grew up in Birmingham in the 1960s, explained why Southerners of her generation “mourned the loss of an icon,” but were not shocked by Watchman’s racist Atticus. “History delivered Southerners of that era into an immoral world where segregation shaped everything,” Russakoff wrote.

At Boston University, Matthews has concentrated much of his teaching and research on the literature of the American South. He is a winner of the Metcalf Award for Excellence in Teaching, the recipient of two National Endowment for the Humanities research fellowships, and the author of several books on William Faulkner. While he shares the concern over whether Harper Lee really wanted Watchman published, Matthews eagerly read the novel. At the same time, he felt compelled to plunge back into his dog-eared, vintage paperback edition of Mockingbird, which he read for the first time in 1963 as a freshman at Central High School in Philadelphia.

BU Today talked with Matthews recently about Watchman and Mockingbird, and how Harper Lee’s relationship to the South played out in her novels.

BU Today: Were you surprised by the racism of Atticus Finch in Watchman?

Matthews: I’d read about it before I read Watchman. I think there’s a kind of continuum with Mockingbird’s comparative indifference to the lives of black people. I have a former student—I taught her in a Faulkner class 10 years ago—who says she doesn’t understand why people are upset about Atticus being a racist in Watchman. She thought that was obvious from To Kill a Mockingbird.

How do you see that in Mockingbird?

Atticus embodies the systemic racism of white paternalism. It’s white people who take responsibility for black people’s problems. This is what Toni Morrison meant by calling Mockingbird a “white savior” narrative. No question, there’s a bravery in what Atticus does in To Kill a Mockingbird. It’s just that all the circumstances around him suggest he’s still a person with prejudice operating inside a world that is blind to the full humanity of black people. That, I think, is how Watchman is somewhat different.

What do you think Harper Lee’s intention was with Watchman, the original manuscript that seems to have become Mockingbird?

I think the book is probably closer to what Harper Lee felt when she began writing it in the 1950’s. By then she was living in New York City. She had left the South. She had identified with an art crowd in New York. Truman Capote, a childhood friend, was there, and other young writers. The 25- or 26-year-old Scout—Jean Louise—who comes back, I think she is closer to Harper Lee’s relationship to the South.

Do you buy the reconciliation with her father at the end?

Well, I do, but I think that’s part of the weakness of Watchman and To Kill a Mockingbird. Lee may not have had the courage of her rage. Part of the ambivalence is Scout’s inability to free herself from that orbit—of that idolatry of her father and what that symbolizes in Southern culture. Part of the pathos of Watchman is that the South can’t repudiate that sort of core regard for the past, for a certain way of life, and for a certain patriarchal society. I don’t mean to reduce it to autobiography, but in the novel, Scout can’t grow up.

What about the sense at the end of the book that Jean Louise is going to come home?

That sense of resolution, of reconciliation, of coming back to the South, of working to improve it, seems to be a vision of some kind of organic transformation of the South. That’s the classic way the white majority South approached change that it recognized to be inevitable, but did not want to come quickly or violently. It was also the kind of gradualism that frustrated and enraged African Americans and some more liberal white Southerners, too.

You can feel in Watchman the great point of irritation for Atticus is the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that outlawed segregation in public schools. I think Atticus’s feeling—and this reflects his racism—is that the South understands segregation to be a problem that has to be worked out on its own terms. You can’t force people to change their attitudes or their minds—it has to be organic. But it’s also impractical because African Americans are perpetually thought to be unprepared for rights of various kinds by white Southerners of a certain class.

I was surprised that Jean Louise—Scout—went along with that in Watchman.

That surprised me, too. I don’t believe it, actually. It’s not a believable ending because Harper Lee didn’t solve the conflict between Scout’s loyalties and her commitment to change in this book.

You can feel in Watchman the great point of irritation for Atticus is the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that outlawed segregation in public schools.

How do you think Watchman might have evolved into Mockingbird?

I think what Lee’s original editor, Tay Hohoff decided, and I think Harper Lee bought into this, was that the book should be something else. She took 2 ½ years to revise it. I think what they wanted to do was create a narrative that provided a model for how the South could reform itself, and there’s a kind of conservative agenda to that, I suppose, in the sense that the white South was pictured as to be trusted to address its issues without the threat of [so-called] hostile intervention from the federal government. And there’s also a bigger, wider narrative, a Cold War narrative. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet Union was using the treatment of blacks in the South as a point of propaganda. They were arguing that American democracy could be discredited because of the way it was treating people of color. You could see how that would play in Africa and Latin America—in all the places the US was so concerned about having credibility.

What did you think of that scene in Watchman where Scout visits Calpurnia, who had cared for her when she was young?

I thought it was really powerful because she goes to Calpurnia’s house. What’s interesting is how communication fails. There’s a very enigmatic, ambiguous moment in which Scout—Jean Louise—says, ‘Did you hate us?’” Calpurnia shakes her head. I read this as Lee leaving some ambiguity.

In Mockingbird, you never question that Calpurnia loves Scout and Jem.

Scout never questions it. That’s why this is a piece of literature and not a history—because it’s a fantasy. It’s a fantasy about a society, it’s a fantasy about the South’s capability, its own moral capacity to handle the question of the extension of black rights. It’s a national fantasy partially in a Cold War context, but also deep in our tradition that a liberal democracy gradually extends rights to those who “deserve” them.

I thought Mockingbird inspired a lot of Northern liberalism in a good way.

I think it did. It sensitized northern whites to racial injustice in the South, in ways similar to what Uncle Tom’s Cabin did a hundred years earlier on the issue of slavery. But when we think of the civil rights movement, too many Americans still think of white people from the North going to the South. We don’t think about African Americans in the 1930s working away, laying the foundation brick by brick, town by town, state by state, being lynched for speaking out. It’s a complex story and it’s full of shifts, and I think that’s what makes Watchman and Mockingbird diagnostically interesting. It’s like looking at a CAT scan.

In what way?

You see the healthy parts, the diseased parts. You have to interpret it. The South, the individuals in it, it’s not one thing. Mockingbird/Watchman is kind of a cross section of the American psyche, too, since Atticus’s nobility allows a form of self-congratulation for white liberal sensitivities in Mockingbird.

Why do you think so many critics are calling Watchman a failed novel?

It’s a book that doesn’t know what it’s doing exactly. There’s all that stuff about Tom Swift and children’s fantasy lives and then suddenly there’s tremendous anger from Jean Louise that culminates in a long talky confrontation with Atticus.

The differences between the two books are extreme. This is not just fussing with sentences, sharpening narrative angles. It’s a complete relocation of the story. The writing is far better in Mockingbird, Lee has control of more descriptive things, the introduction of characters, the weaving of plot and dialogue. Mockingbird is unquestionably a powerful novel.

All of this attention to these two novels—isn’t it, in a way, a validation of what you do, as a literature professor?

I hope so—especially these days, when you think about the alleged crisis in the teaching of the humanities. I’ve spoken with so many readers who remember very powerful experiences reading Mockingbird, some who refuse to read Watchman for fear of spoiling their admiration for Atticus and their identification with Scout’s coming-of-age. Those readers talk about what this novel meant to their development as human beings.

Sara Rimer can be reached at srimer@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.