Reclaiming a Common Language

How a new literary history could help salve wounds in Asia

BU’s first Mellon New Directions fellow, Wiebke Denecke, will travel across East Asia researching Classical Chinese, the region’s forgotten lingua franca. Photo by Tim Gray

Imagine if the Irish refused to read James Joyce because he wrote in English, the tongue of the colonizer. Imagine if French historians willfully ignored ancient accounts of Gaul, because they were written in Latin, language of the invading Roman legions.

To a great extent, that is the attitude informing today’s cultural and educational climate in East Asia. A vast trove of literature penned in Japan, by Japanese poets, and for a Japanese audience is sorely underappreciated in Japan simply because it was written in Classical Chinese, says Wiebke Denecke, a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of Chinese, Japanese, and comparative literature. Once the “Latin” of East Asia, Classical Chinese was the shared language of government, Buddhism, scholarship, and high literature for almost two millennia. In the early 20th century, the Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese abandoned Classical Chinese, promoting their vernacular tongues as their nations’ official languages. One result of this was that the region lost a common literary heritage. Rediscovering Classical Chinese, Denecke argues, might help East Asia heal the war wounds of the recent past.

A German native who has lived all over the world and is fluent in a dozen languages, Denecke was the East Asia editor for the Norton Anthology of World Literature (third edition, 2012). And this year Denecke became the first BU recipient of an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s New Directions Fellowship. The fellowship will allow Denecke to travel with her family to China, Korea, and Japan throughout next year to research all-but-forgotten poetry from the 7th through 12th centuries C.E. She believes these ancient documents may hold an important key to harmony in East Asia, promoting what she calls a “positive transnational identity.”

“One of the things that makes East Asia distinctive is that they have a very long cultural tradition,” Denecke says. That tradition has been carried through hundreds of centuries by a writing system still readable today. “You can see the dynamic of literary creation, reception, and renewal play out over a long duration, which we cannot yet see with the comparatively short history of European vernacular languages. Once people realize that Classical Chinese was a tremendous asset before the modern period and the invention of ‘national literatures,’” Denecke hopes, then they can begin moving toward reconciliation by looking back to a shared history.

The scripta franca

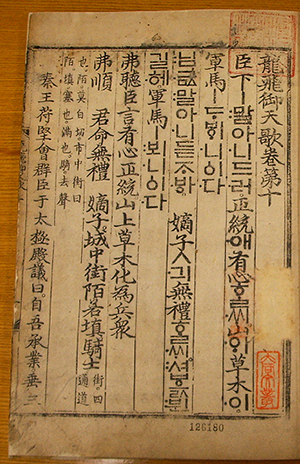

For almost two millennia, Classical Chinese was the lingua franca—or better, Denecke says, the scripta franca—of East Asia. It uses a logographic script, in which each character represented not a sound but a word. The history of writing started with such scripts. But while cuneiform, hieroglyphs, and Mesoamerican glyphs have long since died out, Chinese—which is actually three millennia old, having been in use in China for a thousand years before it began to spread—survives today as the world’s only logographic script. As the sphere of Chinese influence grew to include the preliterate areas now known as Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, those peoples’ rulers, diplomats, administrators, merchants, poets, and monks adapted the Chinese script and the literary language of Classical Chinese to their own use.

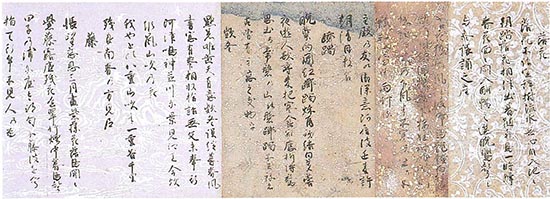

Few people even in the educated classes were bilingual—they spoke only in their own local vernacular—but most in the educated elite became “biliterate,” as Denecke has explained in her latest book, Classical World Literatures: Sino-Japanese and Greco-Roman Comparisons (Oxford University Press, 2014). That meant they could write in their own vernacular as well as in Classical Chinese. When meeting with a foreigner, one would converse in “brush talk”—by passing notes back and forth. Although pronounced differently—often radically so—the same written Chinese characters had the same meanings for everybody across the region. Denecke likens this mode of communication to the Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, etc.), “which are intelligible when American tourists write them down during noisy negotiations over the price of a silk scarf in a market in Cairo.”

Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese also used the Chinese script to write out their own vernacular, and they eventually developed their own scripts. (Today, Chinese characters are used only in China, Taiwan, in hybrid form in Japan, and in very limited fashion in Korea.) But Classical Chinese continued to serve as “the language of government, of church, of high literature” for the whole of East Asia, says Denecke. It was a highly convenient mode of communication for a multiethnic, multilingual region that shared similar education and legal systems, and literary and artistic traditions. Moreover, the script was a vehicle for the spread of ideas—of philosophy and religion, Confucianism and Buddhism. And so it remained until well into the last century. “My senior colleagues in Japan still talk about their grandparents writing poetry in Classical Chinese,” Denecke says.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, nationalism swept the globe, with East Asia no exception. Roles reversed as Japan grew imperialist ambitions and invaded and colonized many of its neighbors, including China and Korea. Those invasions left a legacy of bitterness that persists in the 21st century. For comparison, Denecke points to France and her native Germany, also ardent foes in the first half of the 20th century. Today, those nations are united by a common currency and even a parliament under the European Union, which would have been unthinkable 75 years ago. No such warming of relations has occurred in East Asia, with nationalisms fueled by current economic and military competition. To this day, many Chinese refer to their old enemies as riben guizi, “Japanese devils.” For their part, many Japanese downplay what Denecke considers the undeniable Chinese influence on their language and culture.

As a result, scholars in Japan—indeed, all along the fringes of China’s old empire—focus solely on writings in their own national language, “which has led to this sad situation, where Japanese literature written in Classical Chinese is not taught in schools as part of Japan’s national literary heritage,” says Denecke. “There is a fading bit of training in Classical Chinese—reading Confucius and other Chinese classics—and there is vernacular literature. In between, there is an unacknowledged, gaping hole….This ancient collective knowledge and memory has virtually disappeared within a couple of generations.”

With her Mellon fellowship, Denecke, who has researched Chinese and Japanese literature and history for two decades, will address another gaping hole, namely the missing link in the story of China’s influence on Japanese culture: Korea.

“Especially in the early period, most of Chinese knowledge and products came to Japan through Korea: great artisans who knew how to make silk or Buddhist sculptures, and build monasteries. Especially during the Tang Dynasty, in the late seventh century, the Korean peninsula, formerly divided into three Kingdoms, was unified under the state of Silla and the entire elite of the defeated state of Paekche fled to Japan,” she says. “Most of the composers of the earliest national chronicles and of poetry, and the professors at the newly founded State Academy in the Japanese capital, were of Korean descent.”

The fellowship will allow Denecke to pick up Korean, through intensive tutoring (“with a former BU colleague,” she points out) and courses in Seoul (“alongside BU students studying Korean”), and to dive into premodern Korean literary studies. She will work on two book projects: one on the early history of Japanese poetry, as seen through Chinese and Korean eyes, the other an illustrated anthology of poems written by Chinese, Japanese, and Korean envoys. For this one, she will travel to sites across Japan where foreign envoys stayed and conversed with the locals via brush talk. She will sift through archives and visit related temples.

“Poetry played such a big role in East Asian diplomacy,” Denecke says. “As an envoy, if you don’t speak the language of your hosts, you’re going to dash off a poem in Classical Chinese to express your friendship, to express your sense that you belong to the same common world.”

Indeed, she adds, “poetry” is misunderstood when viewed through the lens of the West, where poetry has long been relegated to the realm of the personal and rarified. In traditional East Asia, she says, before the region imported Western notions of literature (as it did nationalism), “poetry was the most esteemed genre, a tool for expressing one’s worldview, showing one’s historical and ethical judgment and one’s cognitive powers of observation, and also a means of providing ethical guidance, entertainment, and helping communication between social classes, even the sexes. In short, poetry encompassed the world and human life.”

Winds of change

When her work on the fellowship is done, Denecke will have significantly expanded not only her own research profile, but BU’s as well. Thanks to the intensive training in Korean, Denecke will be one of the very few scholars in the world conversant in the languages and classical literatures of China, Japan, and Korea. The timing is perfect, Denecke says, as her home department is currently developing a graduate program in comparative literature with a focus on East Asia.

Being a Western scholar of classical East Asian literatures comes with advantages. Denecke has been attending and cohosting conferences and workshops in China and Japan, and academics are sometimes more willing to listen to Denecke’s outsider perspective than they would to the same facts presented by someone from just across the Yellow Sea. Some colleagues there have told her that the work she is doing is crucial, but that only scholars from outside East Asia have a chance to combat the nationalism distorting its literary studies. That positive reception gives her hope that the regional reconciliation she seeks can become a reality.

While teaching the BU course Classical Chinese for Students of East Asia, Denecke has already seen signs of a thaw among the young Chinese, Japanese, and Korean students who share the classroom with their American peers. “They come in with these very strong national identities,” she says. “You can sense the tensions among these nations in the classroom. And the great thing is, as the course progresses, and I assign them to read Chinese-style texts from Korea and Japan and so on, students really realize, ‘My God, we have a shared heritage. We have to recover that.’”

That is one reason Denecke loves teaching as much as she does research: “You hope to make a difference in students’ lives and teach them about other places, or for our Asian and Asian heritage students, their own places in a different way. Especially in a world that’s so war-torn and where we’re so much divided by religion and ideology and whatever, doing that kind of very slow work of education and empathy with very different places in time and space, it’s very meaningful to me.”

A version of this story was originally published on BU Research.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.