Honoring Life

GRS alum ensures lives lost on 9/11 don’t disappear from history

Jan Seidler Ramirez (GRSu201985), 9/11 Memorial Museum chief curator, says that because 9/11 was u201cone of the searing social, political, and cultural events that affected all forms of human expression, we were going to collect all forms of human expression.u201d Each letter in the quote behind Ramirez is made from recovered World Trade Center steel. Photo by Chris Sorensen

The conference table was bare except for a biohazard bag. Jan Seidler Ramirez, chief curator of the as-yet-unbuilt 9/11 Memorial Museum, waited in silence as Eileen Fagan unsealed the bag. It contained a charred pocketbook that had belonged to Eileen’s sister, Patricia, an Aon insurance adjuster who had worked on the 93rd floor of the World Trade Center’s South Tower. Ramirez found that “there was nowhere else to look but at that pocketbook” as Fagan lovingly removed its contents: a pair of glasses, a rosary, a change purse for alms, prayer cards, and two tubes of lipstick. As she set each item on the table, Fagan explained to Ramirez and her colleagues that her sister had enjoyed chatting with the local teens who worked summer jobs at Macy’s. To boost their sales, she’d buy lipstick, always the same shade of pink.

“We were so worried about Eileen, and how emotional this must have been for her,” says Ramirez (GRS’85). “This was her only sister—and all she was concerned about was us.” Fagan asked how Ramirez and her colleagues were coping with their heartrending work and promised to pray for them as they met with other victims’ families. She donated her sister’s pocketbook to the museum, then only in the planning stage. Ramirez was moved by “her grace and her faith that we were going to be able to honor her sister,” she says. “It was such a profound moment for me and my staff as curators.”

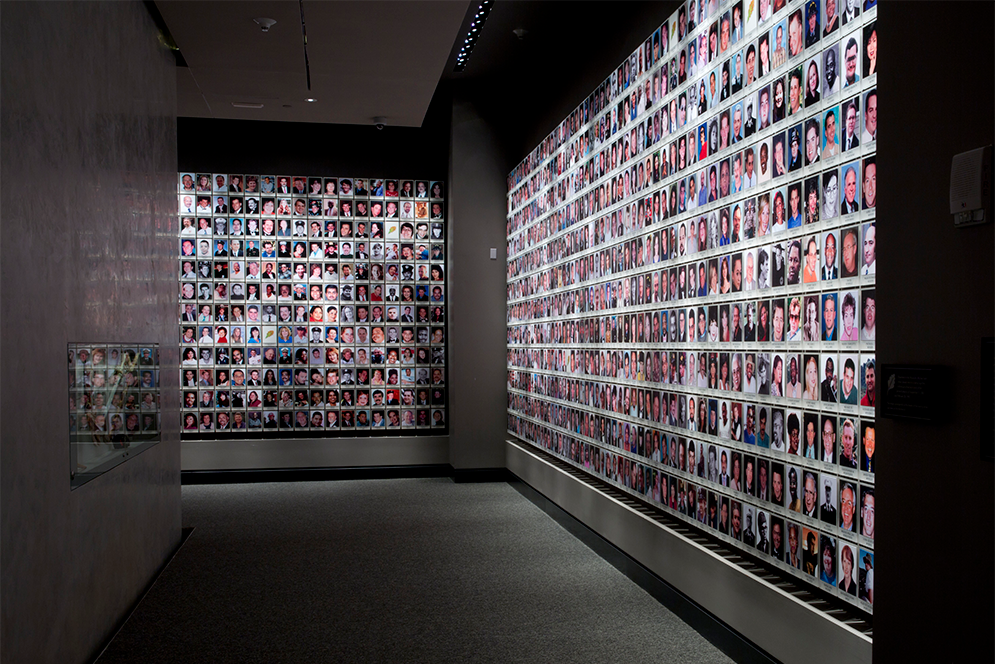

The pocketbook and other artifacts given by victims’ loved ones became the touchstones for the collection Ramirez would assemble at the site where 2,753 people lost their lives.

The DNA of objects

Ramirez was museum director and vice president of the New-York Historical Society just off Central Park when al-Qaeda hijackers crashed two planes into the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers on September 11, 2001. As she watched the news on a television in the museum’s loading dock, another plane slammed into the Pentagon in Virginia, and a fourth went down in a Pennsylvania field.

Like so many others watching in horror that day, Ramirez ached with a “need to do something meaningful,” but felt powerless to help. “I did not have the hands-on skills needed in Lower Manhattan,” she says. “There was nothing I could really do to make a difference.”

It was the president of the Historical Society who helped Ramirez recognize how she might put her expertise to use. “You’re not an ironworker, you’re not a backhoe operator, you’re not a firefighter, you’re not an FBI agent,” he told his staff a few days after 9/11. “But you are historians and curators and archivists and conservators. Your job is to make sure this event doesn’t disappear from history.”

Galvanized by these words, Ramirez and her colleagues helped firefighters manage the sidewalk shrines that sprang up in New York in the days after the tragedy and obtained clearance to watch the wreckage being sifted at Staten Island’s Fresh Kills Landfill. They advised investigators to salvage any items—beyond the evidence and victims’ personal effects under their purview—that might be relevant to an understanding of the attacks. “Objects have a kind of DNA presence about them,” Ramirez says. “They were eyewitnesses to an event.”

On the sidewalks of New York and the conveyor belts of Staten Island, Ramirez gathered teddy bears and twisted metal. And when the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation proposed a memorial museum for the World Trade Center site, she joined the planning committee. She became head curator in 2006 and began the daunting task of assembling the museum’s collection as the wounded city looked on.

She solicited advice from colleagues at institutions like the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum—founded after the 1995 bombing that killed 168—and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, asking, “How did you do it? Where did you start? Where did you limit yourselves?” Ramirez says that her research led the curatorial team to conclude that because 9/11 was “one of the searing social, political, and cultural events that affected all forms of human expression, we were going to collect all forms of human expression.”

She forged partnerships with organizations that had been collecting and generating artifacts, such as the American Red Cross and the Salvation Army, and began collaborating with people and groups that had become “accidental holders of collections—for instance, while housing out-of-state volunteers, the Gramercy Park Block Association had accrued an archive of early response materials like banners and drawings.

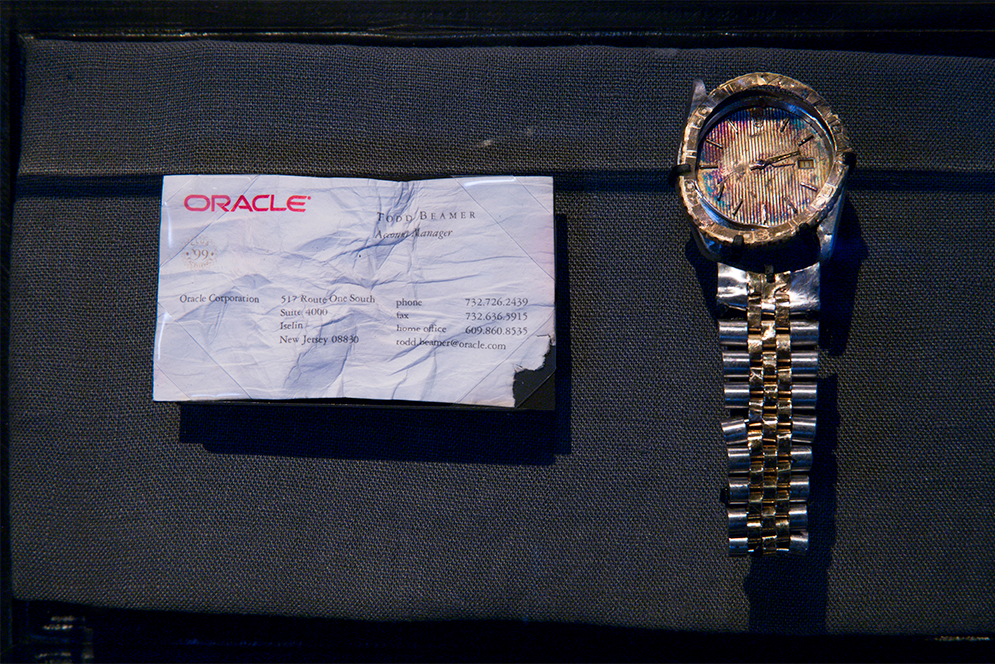

In 2010, the 9/11 Memorial Museum sent victims’ families an official invitation to donate objects that would personalize their loved ones for museumgoers, an ongoing responsibility Ramirez and her colleagues approach with great respect. Families sent thousands of items: a St. Florian medal, a coach’s whistle, a bracelet, a watch, a fire chief’s helmet, as well as notes, photographs, and recorded remembrances. As she told the New York Times, Ramirez is ever mindful of the “etiquette quagmire” of collecting—and rejecting—such objects for “an on-site institution where, for 40 percent of the families of September 11 victims, this is the last known corporeal place where their loved ones existed.”

But the curators had to make decisions. Some objects, for instance, love letters and diary confidences, seemed too intimate for public exhibition.

Ramirez navigated the quagmire by informing donors from the beginning that the museum could not promise objects would be on view at specific times, or in perpetuity. “We are professional caretakers,” she says. “When families take something very personal and make it publicly accessible, they are giving up their own stewardship of it and consigning those responsibilities to us. They had to be ready to do that.”

Not all families were. To date, about half of the victims’ families have donated objects, although Ramirez regularly receives packages from those who “most likely waited until they felt ready to see the museum so they would understand the kinds of things on view,” she says. “And then they went home and thought hard and decided it was time.”

In the slideshow above, view images of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum and some of the artifacts displayed there.

Ground Zero

The 9/11 Memorial Museum opened in May 2014. Constructed on half of the 16-acre World Trade Center site, it adjoins the repository for the unidentified remains of 9/11 victims, a separate space operated by the New York City Medical Examiner exclusively for the victims’ families. In building on a location in “the heart of the wound,” Ramirez confronted the challenge of devising a narrative for the museum that would reflect its dual purpose: investigating the complexities of 9/11 and commemorating the dead.

“The emotion of the site continues to clutch at you,” she says. “It’s a hugely powerful, raw space.” When designing the route visitors would take through the museum, the architects and curators collaborated to preserve that power and “let the site convey its own sense of rupture and loss.”

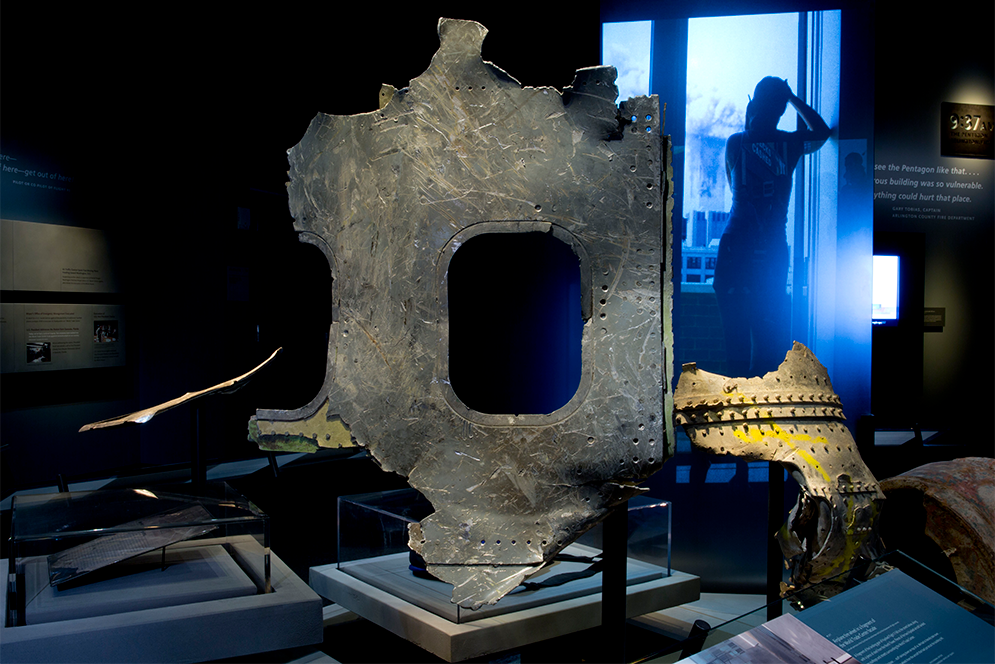

Visitors to the museum enter through a pavilion and descend into Ground Zero on ramps reminiscent of those used in constructing the World Trade Center in the 1960s and ’70s, and in clearing the site after 9/11. The ramps lead to Foundation Hall, a cavernous space with 40- to 60-foot ceilings, bolstered by the original slurry wall that held back the Hudson River when the towers collapsed. Visitors then make their way to the museum’s lowest level alongside the Survivors’ Stairs, the remnants of the Vesey Street stairs used by hundreds to escape from the North Tower. In these exhibits—and as they journey through the museum—they experience the story of 9/11 through audio, video, photographs, architectural salvage, personal items, and other objects, from a fire truck torn in half to an airplane fragment.

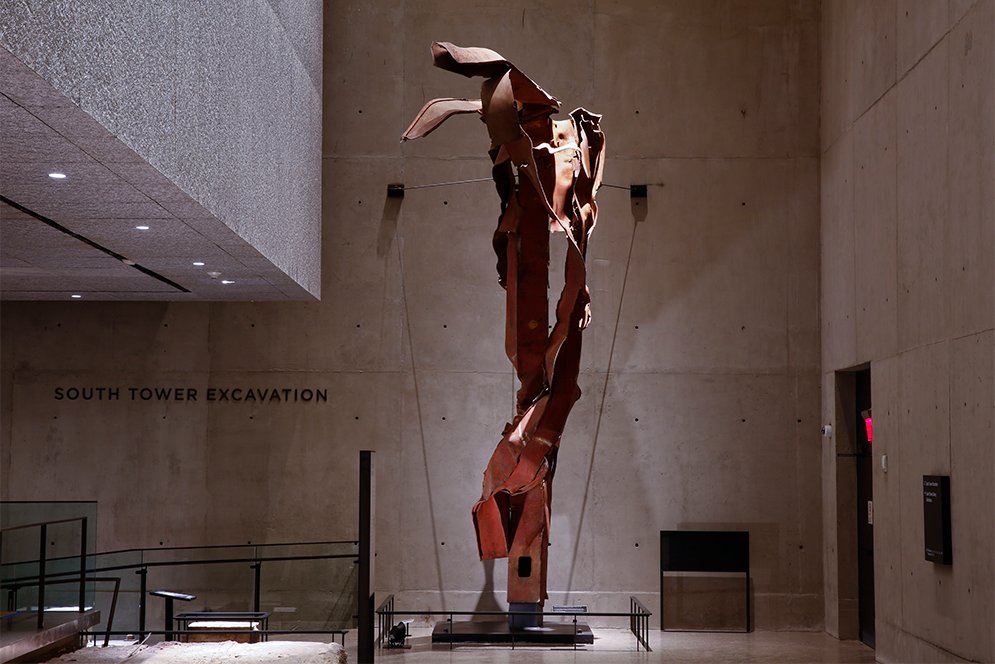

As the collection expanded (it now includes more than 10,300 artifacts), the curators considered how to integrate each object into the museum space when Ground Zero, too, was a relic. One striking piece of infrastructure, an approximately 22-foot-tall pillar of torn steel from the spot where Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower, “is extraordinarily powerful as a tortured witness object,” Ramirez says, but like many other artifacts, it posed a curatorial challenge. “Do you put it on a pedestal? Is that too aestheticized? Do you leave it on the floor? Is that perceived as too disrespectful?”

The curators had long deliberations about whether to present the “indelible, horrific images of people falling to their deaths, which were certainly part of the catastrophic makeup of that horror,” she says. The curatorial team ultimately displayed the images as projections behind a wall marked with an advisory label. And while acknowledging that including the photographs is controversial, Ramirez asks, “If you edited out those images, what else would you be accused of sanitizing?”

There were limits, however. The curators were also the keepers of graphic photographs. “Did a memorial museum that had the repository of human remains actually then show pictures of those remains on the sidewalks of New York?” she says. “We decided that although the archive would collect and hold such documentary evidence, we would not present it in the museum.”

Ramirez and her team showed the same care as they weighed the ethics of displaying the most intimate of items donated by families. Artifacts like Patricia Fagan’s pocketbook “should not be displayed in a forensic style, flattened like on an autopsy table,” she says. “These objects are the bridge to an irreplaceable human being. They need to be conveyed to the public in a more protected, reverent form.”

When determining the presentation of such emotion-fraught relics, Ramirez, who earned her doctorate in BU’s American and New England Studies program, had to set boundaries. “There were certainly families, survivors, and donors who had ideas about how their things should be displayed,” she says. To address such input, the curators were clear with donors that they were “key informants to the story we were going to tell, but they were not the editors and publishers of it.” That role belonged to the museum and exhibition design professionals like Ramirez who were hired for their experience in presenting complex historical stories in public form. “I think that engendered real confidence over time,” she says.

The curators displayed Patricia Fagan’s pocketbook on charcoal gray fabric with its contents carefully arranged beside it. Ramirez says Eileen Fagan is touched that her sister’s belongings rest adjacent to a 17-foot steel crossbeam that stood tall among the wreckage, an icon of hope that rescue workers baptized the Ground Zero Cross.

Reset, renew, rebuild—and live

Ramirez intends for the majority of objects to contribute to a message of hope. September 11, she says, “isn’t specifically an event about 19 hijackers who managed to pull off this catastrophic plot. It’s about how we as Americans are wired to respond to an assault on our core identity. We honor life here; we don’t venerate death. That’s the first huge shift from being a graveyard.”

Before they leave, visitors are invited to further this message of resilience by sharing their own stories in recording booths; they also see a 35-foot projected timeline that continuously updates with related stories of breaking news events around the globe, including other acts of violence against innocent people. Almost every day, Ramirez says, there is an event somewhere in the world that recalls 9/11.

“People are too sophisticated to expect a fairy-tale ending from a traumatic event in history—but they’re looking for some kind of affirmative statement” as they leave the museum, she says. “And the problem with our core subject matter, which is really terrorism, is that the world is not much better off.

“But what we can do is to remind people through the example of what happened here that there is a collective will to not let the bad guys win. To reset, renew, rebuild, and live our lives enlarged because of what we have learned about ourselves and the people we care about, our community, and our country.

“Nobody would be standing in lower Manhattan today, looking at a transformed skyline and a moving memorial, had people just become frozen with hate or inertia, or with the fear that if we build, then somebody will tear it down again. That’s not what we do. We construct.”

Lara Ehrlich can be reached at lehrlich@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.