One Class, One Day: Deconstructing Bob Dylan

Album by album, a look at the many sides of the grizzled Nobel laureate

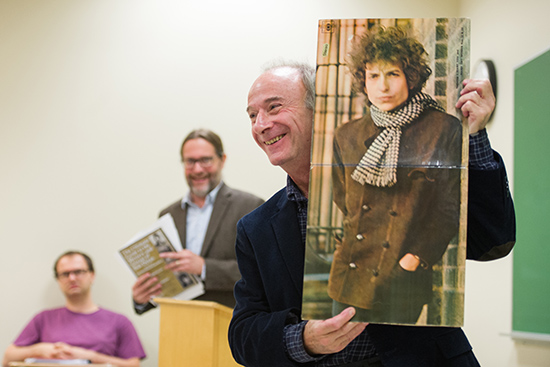

In the class Bob Dylan, Music and Words, Kevin Barents (left) and Jeremy Yudkin focus on the recent Nobel winner’s most compelling albums.

Class by class, lecture by lecture, question asked by question answered, an education is built. This is one of a series of articles about visits to one class, on one day, in search of those building blocks at BU.

Undergraduates who had done their homework know what Jeremy Yudkin means when he kicks off a recent music appreciation class with the ominous words, “Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you?” The class’ many boomer-vintage Evergreen students not only know that these are the opening lyrics of Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man,” they mouth the words along with Yudkin.

Whether you’d been weaned on the inspirational, irascible, and now Nobel Literature prize-winning bard, or were just jumping into his vast canon, the interdisciplinary course Bob Dylan: Music and Words, cotaught by Yudkin, a College of Fine Arts professor of music, and Kevin Barents, a College of Arts & Sciences Writing Program lecturer, appears to be whetting the appetites of a new generation of Dylanologists.

The course, funded by the Provost’s office and made possible by the Center for Teaching & Learning’s Interdisciplinary Course Development Grant Program, focuses on Dylan’s most pivotal recordings, including the singer-songwriter’s inaugural LP, Bob Dylan, recorded in 1962, New Morning, and Blood on the Tracks. This day, the class is devoted to the second LP in the so-called electric trilogy, Highway 61 Revisited, released in 1965. The students had moved from Dylan’s early acoustic records to the trilogy, which begins with Bringing It All Back Home and concludes with the two-disc set Blonde on Blonde. All electric except for the dystopic ballad Desolation Row, Highway 61 Revisited was Dylan’s sixth studio album and is rated by Rolling Stone as the fourth greatest album of all time.

“To give you some context, the Beatles’ Rubber Soul was released the same year,” says Yudkin, who has taught a string of appreciation classes, among them an opera course and a class on the music of Beethoven.

“Where is Highway 61?” he asks. Students pipe up that the road extends from Dylan’s native Minnesota down to Louisiana. But they learn that it is more than a highway bisecting America’s heart. It is highway passing through the breeding grounds of some of the nation’s richest musical heritage, including Memphis, St. Louis, the Mississippi Delta, and of course, the blues, jazz, and zydeco mecca of New Orleans.

“Let’s listen,” says Yudkin, as he plays the album’s opening, unforgettable musical screed “Like a Rolling Stone,” and the room fills with the opening clash of tympani. In the song, Dylan eviscerates a former lover, whose identity is still debated, in his signature nasal drawl. Barents notes that Bruce Springsteen once said the intro sounds like “someone had kicked open the door to your mind” and that Bono has called the song “something to behold,” adding it “turns wine to vinegar.”

The song has become synonymous with Dylan’s controversial first-ever electric set at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965. Unlike some of his more topical work, the song is timeless and the singing is “very intense, cutting, and cynical,” says Yudkin, bobbing his head along with lyrics like, “Ahh you’ve gone to the finest schools, alright Miss Lonely / But you know you only used to get juiced in it. / Nobody’s ever taught you how to live out on the street / and now you’re gonna have to get used to it.” Along with “Positively Fourth Street” and “Most Likely You Go Your Way and I’ll Go Mine,” “Like a Rolling Stone” is one of what Yudkin calls Dylan’s “un-love songs.”

He draws the class’s attention to “the great guitarist Al Kooper on organ. He was a nonorganist.” He points out “the constant loping movement of the drumming, the constant eighth notes on piano, the church-like organ—all behind Dylan’s extremely incisive singing…where Dylan gives up Woody Guthrie’s Okie accent—literally and figuratively, he finds his own voice.” The songwriter himself calls it the best song he ever wrote.

The class is run in a kind of two-part harmony—Yudkin focuses largely on the music and instrumentation (“Close your eyes and listen…”) while Barents shares readings and critiques on the poet. At times, the two share a kind of Siskel-and-Ebert back-and-forth repartee. “Tarantula, a collection of Dylan’s poetry, is not very good,” says Barents. Yudkin: “I definitely agree.”

The students work their way through the Highway album, from “Tombstone Blues,” with its “debt to Chuck Berry,” Yudkin says, to the honky-tonk-infused riffs of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry” to “Ballad of a Thin Man,” a brooding, melancholy song whose title appears nowhere in the lyrics. “The descending half-step bass” sets the dark tone,” he says, noting that “Ballad” placed 18th in Rolling Stone’s greatest songs list.

Time is running out when they get to “Desolation Row,” the album’s final song. “We could spend a week on this one,” Barents tells the class. The song has been called Dylan’s version of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and is “the most devastating of Dylan songs,” Yudkin says. The opening image—“They’re selling postcards of the hangings”—is followed by 11 and a half minutes of hellish imagery. He says that “it seems like this nightmare will never end.” After listening, students share their observations. One likens it to Dali-esque surrealism, while another sees it as a bleak hymn to human loneliness. A third says the song conjures up images of Pablo Picasso’s chaotic war painting Guernica.

Yudkin points out that Highway 61 Revisited propelled Dylan to international stardom. The younger students seem moved and provoked by it. As for the Evergreen students, one approaches Yudkin and Barents after class to thank them. “Bob Dylan has been extremely important in my life,” he says.

This Series

Also in

One Class, One Day

-

November 30, 2018

Breaking Bad Director Gives CAS Class the Inside Dope

-

October 31, 2018

Trump and the Press: We’ve Been Here Before

-

August 3, 2018

A Scholarly Take on Superheroes

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.