Textiles Tell a Story

At Sherman Gallery, Stacey Piwinski weaves the fabric of lives

Stacey Piwinski: It’s not you, it’s me is on view at the George Sherman Union Sherman Gallery through Friday, March 4. Photos by Alexandra Wimley (COM’17)

For Stacey Piwinski, weaving is storytelling. It’s a relationship she has embraced since taking her first Saori weaving class more than a decade ago. A contemporary Japanese textile movement that began in the 1960s, Saori encourages weavers to work freely and expressively. Along with immersing herself in weaving, Piwinski (CFA’99,’00) started building social relationships with other students. “The weaving studio was a place to gain skills and be part of a supportive community,” she says. “The conversations became woven into the fabric row by row.”

That revelation transformed the way Piwinski approaches her art. Using handwoven cloth, discarded materials from a subject, paint, and yarn, she sets out to tell that person’s story in a visual, nonliterary way. Each piece is shaped by long in-person conversations between artist and subject. And while none are meant to be strictly biographical, Piwinski strives to capture the essence of the person being depicted.

Her mixed media portraits are the subject of a vivid new show running through March 4 at the Sherman Gallery: Stacey Piwinski: It’s not you, it’s me.

“Each work conveys something different,” says Piwinski. “Every person’s story is different. Like reading a book, meanings and messages are not instantly revealed. It takes time to find what is concealed in a piece.”

Revealing her subjects’ stories requires a multipronged and labor-intensive approach. She begins by asking people for bags full of objects they would normally discard—“nothing mushy, gross, perishable, or alive,” she says. What people give her ranges from photographs and letters to box tops, car decals, and other random objects. She takes them and laboriously shreds, cuts, twists, and tears them into fabric, literally recontextualizing random objects to communicate her subjects’ stories.

“Much like a writer gathering information to write a biography about someone, I do not do this in isolation,” Piwinski says. “There are times when I need to talk with the person being depicted, and the objects are the catalyst for deeper conversations that happen while I’m weaving the cloth.” The process she uses to create each piece is deeply collaborative.

For Donella, one of the pieces in the Sherman Gallery show, the subject brought snippets of ribbon, a plastic water bottle, an empty box of Goldfish crackers, and a photo of herself with a friend—all now woven into the fabric in the piece. The artist invited Donella into the studio as she worked on the portrait so she could become more involved.

“Donella painted the objects she had given me, and I prepared the loom,” she says. They listened to music and shared stories as they worked. Piwinski began shredding the painted objects and weaving them into a fabric. Additional conversations between the two continued to shape the piece’s composition.

“The objects became the starting point for telling her story visually,” says Piwinski. “The conversations while making the fabric and then how to cut it and compose the piece are much more telling” than the discarded objects. “Each shift is important, the number of pieces is important, and the feeling one gets when looking at the piece is important.” Decisions about yarn and paint colors are also influenced by the conversations between artist and subject.

One series of weavings is based on T-shirts belonging to Bill, a colleague from the Lesley University MFA program. Provided by Bill’s wife, who was only too glad to get rid of items dating as far back as high school, the shirts provided a kind of tactile biography of her friend after Piwinski set about shredding and composing the fabric. “Each shirt was well loved, many with holes worn through them, all with their own stories,” she recalls. As she and Bill talked about some of the memories evoked by the shirts, she noticed marks on a wall in his home where he had measured the different heights of his children as they grew. She incorporated that into the series about Bill and his family, which ultimately became a meditation about the passage of time.

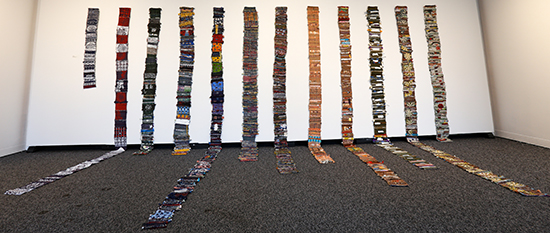

The artist has also plumbed her own life for inspiration. In one piece in the exhibition, 381 Minutes of Letters from Past Relationships, she reworked a collection of letters she had stored in a shoe box into a fabric scroll. Another, titled Two Years, 2014–2015—easily the most ambitious piece in the show—represents a kind of archive of the last two years of her life. During the first part of the project, Piwinski wove strips, each representing one month and each length based on how much she wove that month. “Little bits and pieces from my life became part of the fabric, just like in my work about other people,” she says. In the project’s second year, she cut the strips apart, depending on the number of days in the month. Every day, she added onto the fabric piece by piece using paint or collage, allowing herself to look back to the year before, then sewing the pieces back together.

She was startled by how revealing the finished project was. “To me, even my journals do not tell my story as well as this piece does,” she says. “The piece is about self-exploration and reflection over time. I’m sure it will convey different things to different people as they look closely at all that it holds.”

Piwinski says that for her, weaving is a metaphor “for making connections and bringing people together.” Producing artwork and social exchanges are inexplicably intertwined. “Each aspect is constantly giving to the other: social interactions feed my studio work and my studio work fuels social interactions.”

The work is deliberately labor-intensive. “Now more than ever, it is especially important to slow down and take the time to listen to each other,” says Piwinski, noting that weaving is an ideal vehicle for doing this. In a society where social media and digital technologies are “simultaneously pulling people together and pushing them apart,” she hopes her work serves to remind people about the importance of taking time to connect with one another.

Stacey Piwinski: It’s not you, it’s me is on view at the Sherman Gallery, George Sherman Union, 775 Commonwealth Ave., second floor, through Friday, March 4. The gallery is open Tuesday to Friday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday, 1 to 5 p.m. The show is free and open to the public.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.