Trying to Save an Important Part of Lincoln’s Legacy

BU Trustee Jonathan Cole: rescuing public universities from the budget axe

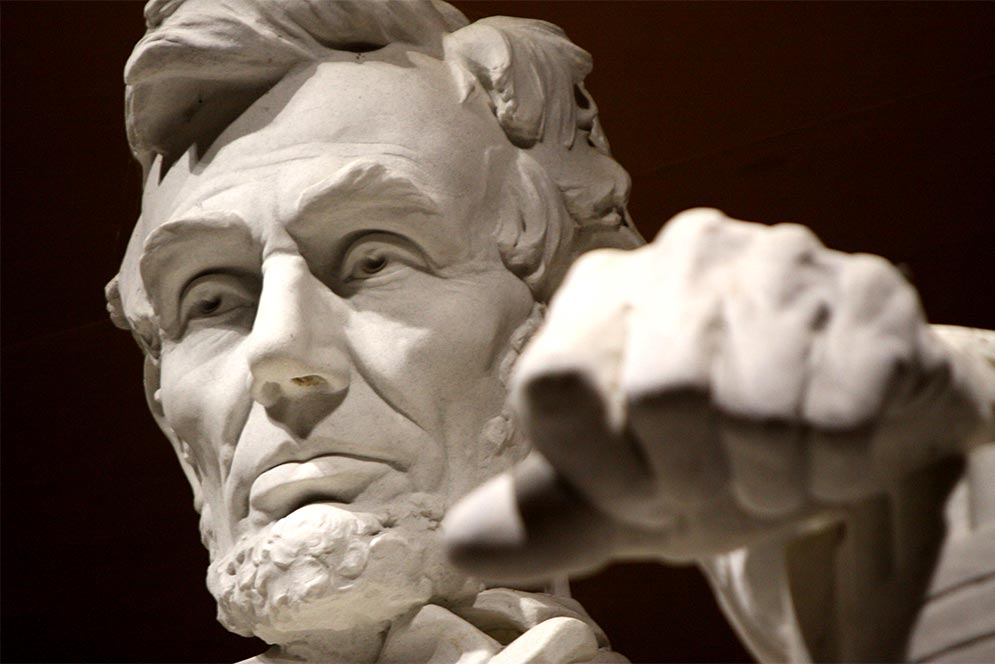

The Abraham Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Photo by Flickr contributor Gage Skidmore

BU trustee Jonathan Cole is trying to save Abraham Lincoln’s education legacy.

Lincoln signed the Morrill Act in 1862, the law creating public colleges and universities, as a way to make higher education available to all Americans, not just the wealthy. But the Great Recession of 2007–2009 drove states to slash budgets for these institutions, jeopardizing their historic mission, says Cole, a Columbia University professor of sociology and provost emeritus. That’s why he joined the Lincoln Project, which was created by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Its members, comprising academic, business, and political leaders, held a series of meetings around the country in 2014 and 2015 with public university trustees and presidents, state lawmakers, and others. The goal was to collect data and make recommendations for reversing reduced support for public higher education, which educates more than two-thirds of postsecondary US students. The project has released a raft of suggestions, headlined by a plea to states to pump more money into their state schools. (State support for public higher ed in recent years has ranged from just over $3,200 per student in New Hampshire to more than $19,000 per student in Alaska.)

Other recommendations by the project—whose full title is The Lincoln Project: Excellence and Access in Public Higher Education—include a new national endowment for public higher education and calls for colleges and universities to aggressively recruit business partners to speed up commercial development of products from academic research, to seek more philanthropic support, and to adopt the efficiencies and money-raising practices of their most innovative peers.

Cole is unpersuaded by the argument that states have other, more pressing, needs to fund. “We have the lowest marginal tax rates in the world,” he says. “You can increase the marginal tax rates on the rich, on the well-to-do, in order to support the ability of kids who come from families who can’t afford it. What I think the Lincoln Project is trying to do is make the public more aware of what they’re losing and how the next generation—their children, their grandchildren—are going to suffer.”

Cole, whose latest book is Toward a More Perfect University, (PublicAffairs, 2016) spoke to BU Today recently about the project.

BU Today: How did someone who’s a trustee of a private university and a professor at a private university get involved with a project to save public universities?

They were interested in the perspective of somebody who had spent his entire career at a private university. In my latest book, my concern is greater for the public institutions that have taken on more of the teaching of our students. The place of publics has now far exceeded what Harvard can do, what BU can do, what Columbia can do. Arizona State is now educating 90,000 undergraduates. Berkeley has four times as many students as Columbia, and the California system has well over 250,000, as does the City University of New York.

Is the primary problem of higher education a matter of too few resources or of quality?

They’re interrelated. If you diminish the resources sufficiently, you’re going to have tremendous damage to the quality of faculty, to the quality of students you can attract. The view that these institutions are not worth supporting reflects a misunderstanding of the role of universities in the states as incubators of economic growth, innovation, and discovery. Universities have had to find alternative sources of revenue, and most of them transferred that loss in state revenue onto the students by increasing tuition, which became prohibitive. Flagship institutions have students who significantly come from well-to-do residents of those states, foreign students who can pay the full price, and out-of-staters.

Was Bernie Sanders’ proposal for free tuition at public universities during last year’s presidential campaign a welcome bit of attention to this problem?

I love Bernie Sanders, but I don’t think his proposal was thought out as well as it might have been. If you are Steve Jobs’ daughter or you’re Bill Gates’ child, why shouldn’t you pay the full price? I thought Hillary Clinton’s proposal was a better proposal, which is sort of free tuition for anybody who could really demonstrate the need.

Is there a state that’s doing public higher education right?

North Carolina has done relatively well in supporting its public institutions. It’s not blue state–red state necessarily. Proposition 13 [limiting property taxes] in California has killed revenue sources.

What do you think the odds are of states, the federal government, and the public buying into and accepting these recommendations?

I don’t think it is more than a .5 probability that it would change in the next four or five years. The country has gone more conservative in certain ways. Second, the state legislatures don’t understand most of it. Arizona has legislators who earn, on average, $35,000 a year. They see professors earning $100,000, and they think, these are privileged people, why do they have to earn that kind of money?

Upward mobility comes through education. I don’t think everyone has to have a college education. They can earn very good incomes—try to get an electrician on Martha’s Vineyard. But those who have the talent should be able to get through without too much of a burden.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.