Museum of Fine Arts Presents Matisse in the Studio

Explores the influence of objects kept in the artist’s studio

Early-20th-century vase from Andalusia Spain, blown glass (left). Former collection of Henri Matisse. Photography by Francois Fernandez. Courtesy of Musée Matisse/Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Vase of Flowers, oil on canvas, by Henri Matisse, 1924 (right). © 2017 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society, New York. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Few artists did more to revolutionize 20th century art than Henri Matisse (1869–1954). While the artist has been the subject of numerous retrospectives in the decades since his death, an exuberant new Museum of Fine Arts show, Matisse in the Studio, presents his work in a compellingly fresh way.

Throughout his career, the French artist collected objects—Spanish vases, African sculptures, tribal masks, textiles, Chinese calligraphy, French chocolate pots, pewter jugs—that inspired him and influenced his development as an artist. Pairing nearly 40 of these objects (many never before seen outside of France) alongside approximately 80 of his paintings, sculptures, cutouts, and drawings influenced by his collection, the exhibition shows how he returned to the same objects again and again with new ideas about color, form, and technique.

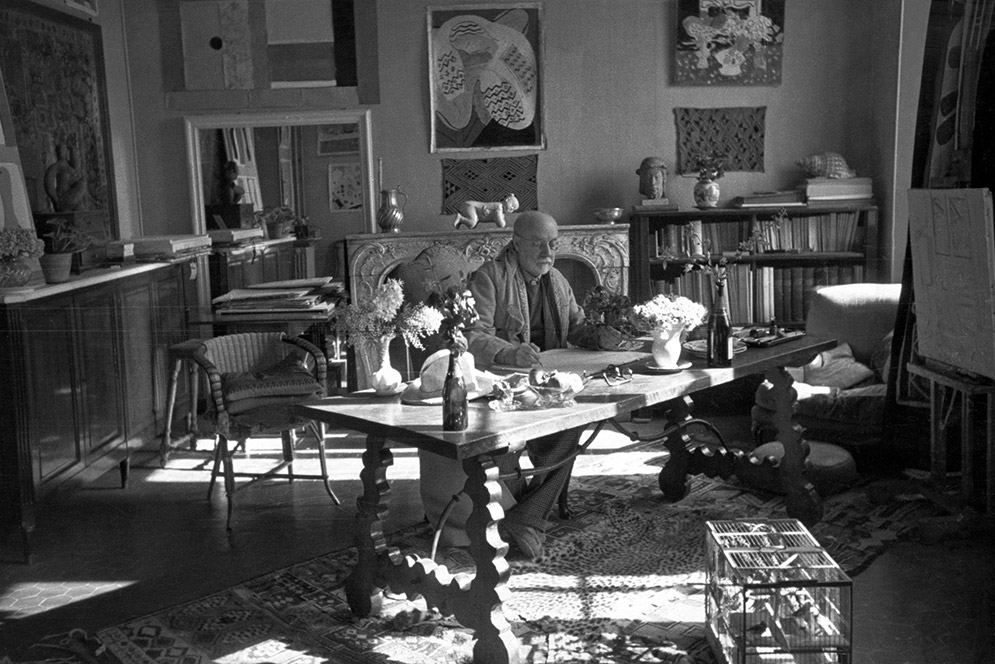

Photograph of Henri Matisse with his collection of Kuba cloths and a Samoan tapa on the wall behind him, by Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1944. © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The show, spanning nearly five decades in the artist’s career, is presented thematically and roughly chronologically and divided into five sections: “The Object Is an Actor,” “The Nude,” “The Face,” “Studio as Theatre,” and “Essential Forms.”

As viewers enter the museum’s Ann and Graham Gund Gallery, they are greeted by a large, early-20th-century blown glass vase Matisse picked up during a trip to Spain, flanked by two paintings the vase figures in prominently. In both, Vase of Flowers (1924) and Safrano Roses at the Window (1925), painted roughly a decade after he acquired it, the vase exerts a sensual quality, serving as a kind of stand-in for a human figure. In each painting, the vase is juxtaposed with different objects (Matisse frequently rearranged the pieces in his studio) and in different light in each painting.

In the next room, two chocolate pitchers, one a wedding gift to Matisse and his wife, Amélie, are next to a number of still lifes and collages featuring one or both vessels. In Still Life with a Shell, a seminal collage he did in 1940 while working out the compositions for a painting, the free-floating cut-paper shapes foreshadow the paper cutouts that would come to dominate the latter stage of his career.

Interior with an Etruscan Vase, oil on canvas, by Henri Matisse, 1940. Courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art. © 2017 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society, New York. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The objects Matisse was attracted to weren’t particularly expensive. He was drawn to things that stimulated him visually. He described his collection as his “working library,” and visitors to the show can see how a piece of furniture or fabric served to liberate him as he experimented with layering, color contrasts, and more.

One of the most important objects in the show is the sculpture of a small seated figure from the Democratic Republic of Congo dating to the 19th or early 20th century, which Matisse is said to have bought in a curio shop in 1906 on his way to dinner with Picasso and Gertrude Stein. Known as a power figure, the piece was designed as a container for spirits or spiritual forces. Acquiring that object, the show’s curators note, turned out to be a “watershed moment” in Matisse’s artistic development.

By 1908, he had collected some 20 African masks and figures, and their influence on his work is evidenced in his nudes that appear in the same room. For Matisse, as the curators point out, the African statues were “a source of game-changing ideas about power and the purpose of image-making.” He began to feel that African artists were expressing something more enduring about the human form than was being conveyed in a traditional Western style. And that conviction is apparent in any number of paintings and sculptures of the human form that followed.

A word of advice: there’s much here to absorb, so give yourself a good two hours to explore the show. The exhibition was conceived by Helen Burnham, MFA curator of prints and drawings, Ellen McBreen, a Wheaton College associate professor of art history, and Ann Dumas, curator of London’s Royal Academy of Arts, where the show will go next. It offers new insight into the creative process of one of the 20th century’s greatest artists. You may never look at a vase, bowl, or coffee pot the same way again.

Matisse in the Studio is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Ave., Boston, through July 9. Find hours and admission prices here (free to BU students with ID). Find directions here.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.