New Book by BU Researchers Teaches Natural Selection to Children

Research-based effort presents complex concepts in storybook form

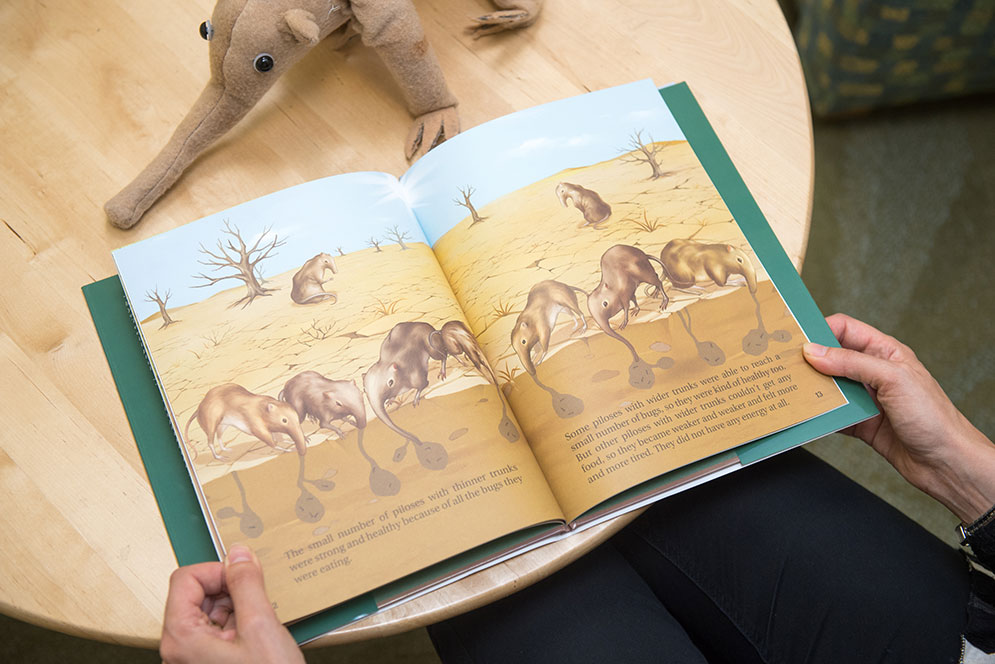

Deborah Kelemen, a BU College of Arts & Sciences professor of psychological and brain sciences, and her research team have published a children’s picture book that introduces the concept of adaptation by natural selection to kids ages five to eight. Photo by Cydney Scott

Conventional wisdom holds that natural selection is too complex for young children to grasp and so should not be taught until middle and high school. The problem with that wisdom, as Deborah Kelemen’s research has shown, is that by middle school, kids’ intuitive biases have taken hold, making it even harder for them to understand the concept. So Kelemen, a Boston University College of Arts & Sciences professor of psychological and brain sciences, and her research team wrote their own research-based book about natural selection, How the Piloses Evolved Skinny Noses, and aimed it at children ages five to eight. Then, with funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Kelemen tested the children, who listened to the book about the fictional anteater-like piloses and found that they got it.

“Kids are smarter than we give them credit for,” says Kelemen, who directs BU’s Child Cognition Lab and studies child development.

Tumblehome Learning, Inc., a Boston-based publisher of children’s science and engineering books, published How the Piloses Evolved Skinny Noses in June 2017, with glowing blurbs from Steven Pinker, a Harvard University psychology professor, and Alison Gopnik, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, both experts on the study of children’s learning.

“Evolution by natural selection is a notoriously difficult concept to understand and this may underpin some of the anti-science views that have become increasingly prevalent,” says Gopnik. “Kelemen has shown that giving young children a simple but ingenious picture book can get them to genuinely understand the concept and that this early understanding is long-lasting. It’s a great, simple, inexpensive idea that could have long-lasting effects, and it would be marvelous for science if every child heard the story of the piloses.”

“Evolution by natural selection is a notoriously difficult concept to understand and this may underpin some of the anti-science views that have become increasingly prevalent,” says Gopnik. “Kelemen has shown that giving young children a simple but ingenious picture book can get them to genuinely understand the concept and that this early understanding is long-lasting. It’s a great, simple, inexpensive idea that could have long-lasting effects, and it would be marvelous for science if every child heard the story of the piloses.”

A big draw for Tumblehome, says chairwoman Penny Noyce, was that Kelemen had grounded the book in research on how kids learn. “We didn’t find another book like this,” says Noyce. “It fits into a niche for us—helping scientists reach a broader audience with books for children.”

For a first-time children’s book author without an agent or a publicist, Kelemen has been enjoying surprising success. After she appeared on the popular BBC radio show Start the Week and on the BBC World Service Newshour in early July 2017, her book sold more than 1,000 copies in a single month—a record for Tumblehome, says Noyce—and it’s already in its third printing.

Kelemen, who shares author credit with the Child Cognition Lab, says profits from the book will go to distributing the book to schools and to further research. How the Piloses Evolved Skinny Noses is the first in a series of books on evolution for kids that Kelemen and the Child Cognition Lab are creating.

On September 18, 2017, Kelemen and her team kicked off a three-week-long, BU-sponsored crowdfunding effort to get the book, which costs $17.95 at Tumblehome, into the hands of teachers and kids across the US who might not otherwise be able to afford it. They set their initial fundraising goal at $2,500, but with close to $2,000 in donations pouring in before the official launch, they have already doubled their goal, to $5,000, and are fast approaching it.

Kelemen says she views her book as a tool in her mission to improve science literacy in the US and abroad. “This anti-intellectual stance that’s happening in this country and across the world is a serious threat,” she says. “People are trying to invalidate scientific evidence by the loudness with which they shout. If you want to fight back, and spread scientific literacy, buy this book.”

How The Piloses Evolved Skinny Noses

Listen to Kelemen read a passage from her recently released children’s book.

Deborah Kelemen“Evolution of the Piloses”

Audio — 1 minute 52 secondsWith an additional NSF grant, Kelemen and her team will design and test a series of storybooks that will revisit and build upon the fundamental principle of natural selection that is introduced in How the Piloses Evolved Skinny Noses.

BU Research sat down with Kelemen recently to talk with her about how she and her research team came to write their first children’s book, why she thinks kids should be introduced to natural selection at an early age, and why she told the illustrator not to make the piloses human-like.

BU Research: Why did you and your team write How the Piloses Evolved Skinny Noses?

Kelemen: There are no evidence-based classroom books for young kids about natural selection. It’s a mechanism that explains why animals have these incredibly specialized body parts and why we have such amazing biological diversity on Earth. Students find it hard to understand the concept when it’s taught in high school. Children are naturally brilliant at generating explanations, but they create explanations that conflict with how evolution actually occurs. What this means is that the lifelong difficulty many people have with understanding one of the most important scientific concepts begins in early childhood.

In biology, natural selection is like the frame that structures your house. Everything else in biology makes sense in light of it. There wasn’t a book geared toward children’s misconceptions. So my team at BU wrote one.

Can you tell us about the story?

It’s about a fictional animal called the piloses whose environment changes. They eat millibugs, which keep them healthy and strong, but as the climate gets hotter, their food goes underground and the piloses species goes from having mostly wider trunks to mostly thinner trunks because the ones with thinner trunks can reach the food and are healthy enough to have many babies. Kids naturally learn the logic of adaptation by natural selection through the story. It unfolds logically, step by step.

Why did you invent the piloses? Why not just write a book starring, say, giraffes—animals that kids know and can recognize?

We always work with realistic but fictional characters. It’s a developmental psychology trick. When children are learning something new and challenging, you don’t necessarily want them to bring potentially confusing background assumptions to bear on it. So you teach them about something they don’t know anything about. If we used giraffes, they might think, “Well, they needed long necks to reach food in the trees so they grew long necks.” But that’s not how natural selection works. We thought, “What’s the simplest story we could tell? What traits would the animal need to make the story work?”

You’ve said that you’re frustrated with a lot of the regular children’s science books that are out there—that they’re too flashy and interfere with actual learning.

We know, based on research, that all those bells and whistles are a distraction. It gets adults very fired up. Children like looking at them, but they don’t actually learn from them. If you want to create learning material, which our book is, you can’t go with the bells and whistles. The whole notion is you’re going to sit down and read the book with a child. Children like that. We always read the book to the kids when we were testing it.

Why?

Partly because this was all developed in a research context. You want the adults to point to the pictures in ways that elaborate the story, whereas children reading by themselves, they’ll just kind of whip through it. We know that joint attention with somebody else facilitates learning.

Why did you insist that the publisher not alter the story in any way and that the illustrator, Chen-Hui Chang, who redid your lab’s original drawings, not make the animals too cuddly—and that they couldn’t be human-like?

Again, because the book was carefully designed in a research context, we discovered what threw children off. Nothing has been changed that could influence children’s learning. By the time it came to publishing, it was really important they didn’t mess with the story or the illustrations. We knew small changes could make all the difference to what children took away from the story.

The animals couldn’t be human-like because you can’t have them looking at each other in ways that suggest they would help each other.

Why not?

If the animals are anthropomorphized, one of the things children will say, when the ones with wider trunks can’t get to the food, is why don’t the animals with thin trunks help them? If animals are proxies for human beings, then if you’ve got a friend of yours who’s starving to death, you’d try and feed them. But these are just animals going around and trying to fill their bellies. Life is hard on the meadow.

Why are you so concerned about teaching young kids about natural selection and not waiting until they’re 13 to 18 years old?

This is such a counterintuitive idea and 13 to 18 is too late. By elementary school, children are cementing their own intuitions that are the roots of scientific misconceptions seen in high school kids and undergraduates. You need to plant the seed early. This is not the full explanation of natural selection, but it is something that does counteract the natural way kids explain animals’ body parts—that animals grow what they need, that everything transforms so that it gets what it needs. That’s not how it works. Populations change over time. It’s a gradual process. In subsequent books in our series, we will show how the same gradual process in Piloses can lead to even bigger evolutionary changes, like new species.

You didn’t have books like this when you were a kid, but you learned natural selection.

I had dinosaur books. That was my fascination. I don’t think I learned about natural selection until I was in high school or university, and it’s effortful then.

Why is this crowdfunding campaign so important to you?

We want to offer teachers—particularly those in underserved schools—direct access to simple materials that can help them accurately teach the basic principle of natural selection to children. We also want to get the word out that this is something that kids can learn and that it is good to start early. Researchers in developmental psychology or education often create materials that can really help kids and teachers, but once the research is over, no one ever gets to use or see the materials again. We want to make sure that does not happen with the piloses and that books, books, and more books are sent out to support science literacy throughout the United States.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.