A Fascination with Disaster

The storied history of Arctic exploration isn’t over. Adriana Craciun is still asking questions.

The storied history of Arctic exploration isn’t over. Adriana Craciun is still asking questions.

The faded sign is nothing more than a simple wooden board, a faint white hand painted on its center, the index finger pointing ahead. But mystery shrouds much of the story behind this 19th-century signpost: the direction it was meant to point, who painted it, or details of its journey into and around one of Earth’s most desolate places.

The direction post is an eerie artifact, one of many scattered relics left behind by English explorer Sir John Franklin and his crew during their final, disastrous 1845–48 attempt to traverse the last unnavigable section of the Northwest Passage. It was found on Beechey Island, in what is now the Canadian Arctic Archipelago of Nunavut, by an 1850–51 search expedition. No longer standing when it was found, it was impossible to determine what the wooden sign—riveted to a seven-foot iron spike—had been leading to. When it was planted it may have been urging searchers toward the HMS Terror and the HMS Erebus, Franklin’s icebound ships. Or it may have been placed to lead the way to Franklin’s grave. There’s no way of knowing. What is known is that all 129 men and both ships were lost, while much was left behind.

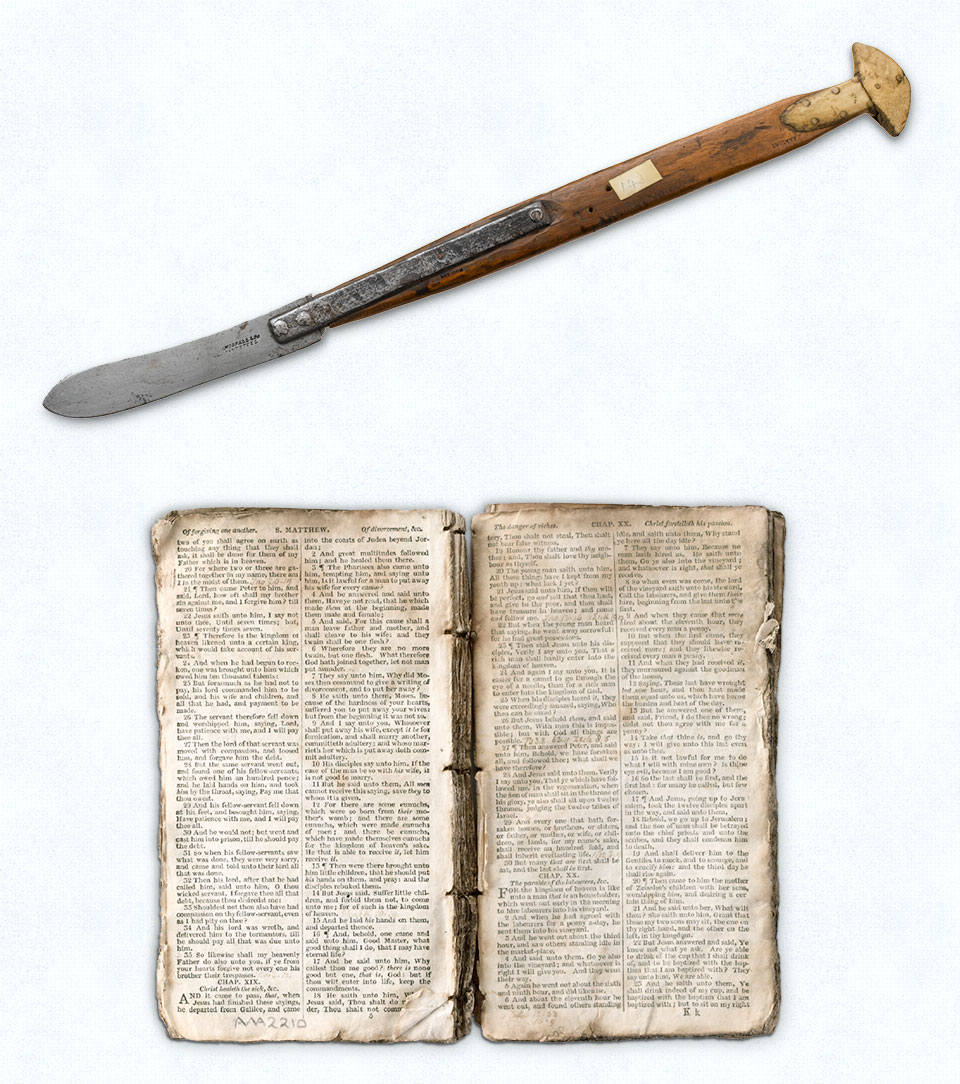

Adriana Craciun, a Boston University professor of English, has delved into the mysteries of the sturdy sign, and other Franklin artifacts. She’s run her hand over the rough iron of the post and seen the tattered Bibles, tinted spectacles, and rusted cans that remain from the ill-fated crew at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, where they’re housed.

For Craciun, the remains of Franklin’s expedition are more than mere objects. She looks beyond these artifacts’ initial utility and seeks their complex beginnings and unfinished stories. “The pointing hand spoke to searchers as almost beckoning them on,” she says. “And the fact that it was found on the ground, no longer pointing in any particular direction, was especially frustrating and evocative. Probably it just pointed to the ships through the snow, to the crew who were camped on land, but that doesn’t stop people from projecting significance upon it. It’s a directionless direction post, a ghostly hand pointing nowhere, the perfect artifact for this expedition’s afterlife.”

Craciun focuses on British literature and culture, with her current research directed at Arctic exploration from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Historical geography, material culture, scientific inquiry, and the history of collecting, books, and authorship are also her purview. Craciun’s most recent book, Writing Arctic Disaster: Authorship and Exploration, looks closely at failed Arctic expeditions and how the dreams, horrors, misadventures, and windswept remains of men and their ships grabbed hold of the 19th-century imagination and became as culturally significant—if not more so—than the expeditions themselves.

Polar journals, Arctic maps

The Arctic’s mystique struck Craciun early. Before moving from Romania to the United States when she was eight, her mother read aloud tales from the polar journals of Fridtjof Nansen, the illustrious Norwegian Arctic explorer and Nobel laureate. “It was one of the few adventure books translated into Romanian,” she says. “Because the Soviets loved him.”

She’s also held on to a 10-franc map of the Arctic Ocean’s floor, purchased in a Parisian bookshop when she studied French as an undergrad. The map has traveled with her to professorships at the University of London, the University of Nottingham, and the University of California, Riverside. But her scholarly pursuits began with topics outside of the icy North.

Craciun spent the first half of her career as a British literature scholar. She’s written two books looking at women writers and their contributions to Romantic-era thinking as it relates to the body, gender, revolutionary politics, and cosmopolitanism: Fatal Women of Romanticism, and British Women Writers and the French Revolution: Citizens of the World. She has also edited essay collections focusing on material culture and collecting, a field that studies objects, the materials they are made of, their provenance, and how those materials and items are central to a culture.

For many years, Craciun was a traditional Romanticism scholar, relying almost exclusively on the most time-honored tool of research: the Book. But eventually, she began seeing each book as an object in itself, a piece of a particular history, every volume holding a story of its own individual geography and travels. Books were no longer exclusively the sum of words inked on pages. In her studies, they became evidence of history, and not just content. “Textual, or book, history looks at books and written texts as material objects, considering everything from the type of paper, the size and price of the books, the geographic travels of book distribution, the decay and repurposing of books through their often long and extraordinary lives,” she explains.

Her research approach of combining textual resources and material culture continued to develop, and now she gazes true north, focused primarily on the Arctic. Her work is rich with the region’s lost ships, ghostly signposts, British knives reshaped into Inuit tools, journals written by dying men, and the deep culture of the indigenous people who were there long before the foreign ships arrived. “I’ve fallen hard,” she admitted. “I’m totally in love with this field. I was a literature scholar, and had specialized—like we all do—in certain things. I decided I was going to do something completely different and realized that in order to do it well I had to learn about different disciplines, geography and history of science especially. I had to become a beginner.”

One example of an artifact that Craciun discovered is James Isham’s Observations on Hudson’s Bay, a 1743 manuscript book that had been forgotten or ignored in the Hudson’s Bay Company archives in Winnipeg, Canada. Within the book, Beaver Hunting, an anatomically and technically detailed watercolor illustration, shows Cree people hunting, and includes a 30-point explanatory key. To Craciun’s trained eye, the illustration shows far more. “I think it may have been painted by a Cree illustrator, and at the very least shows the interconnected worlds of the Cree, English, and animals on the Hudson Bay, before the 19th-century British popularized their images of the ‘empty’ and ‘uninhabited’ Arctic,” she says.

Craciun’s Arctic research covers nearly 400 years, and several disciplines. Ann Cudd, former dean of BU’s Arts & Sciences, is an ardent supporter of Craciun’s diverse approach to academic inquiry. “An interdisciplinary scholar is something we want in CAS and in BU as a whole,” she says. “Adriana is bringing perspectives from material culture, art history, anthropology, and science studies, as well as women, gender, and sexuality.”

Craciun has a long record of collaboration, with scholars in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and Norway. “A lot of people talk about interdisciplinary work, but she really does it,” adds Mary Terrall, professor of history at University of California, Los Angeles, who worked with Craciun on a series of conferences and a volume of essays. “She was very proactive about contacting others at UC who might have shared interests.”

In addition to research and teaching, Craciun edits Studies in Romanticism, an important, if occasionally insular, academic resource on Romantic literary studies that was founded at BU in 1961. Cudd hopes that Craciun’s wide-ranging interests and broad research will reinvigorate the journal. “I think she’ll bring a more contemporary approach, from gender studies and materials studies, and those perspectives and approaches will broaden the readership and interest in the journal,” Cudd says.

The Terror and Erebus have recently drifted into present-day controversy, amid a sea of questions about indigenous rights, mineral extraction, and artifact repatriation

Image courtesy of National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

A Sea of questions

The 19th century’s lost European explorers, their failed missions and ice-crushed ships, are far from contemporary. But Craciun’s research into polar exploration—and Franklin’s expedition in particular—has elements that are entirely current. The Terror and Erebus have recently drifted into present-day controversy, amid a sea of questions about indigenous rights, mineral extraction, and artifact repatriation.

Search parties pursued the remains of Franklin’s expedition for nearly 170 years, until, in two remarkable discoveries, the submerged ships were found: Erebus in 2014, and Terror in 2016. At that point, the story of Franklin’s expedition turned toward the future. Craciun’s Arctic disaster book had just gone to press when the Erebus was found. “I don’t usually have a problem being overtaken by contemporary events,” she says.

“Objects have distinct lives and now we speak of their biographies, not just their histories”

The sunken ships were found in the icy waters of Nunavut, Canada’s newest, largest, and most northerly territory. Officially separated from the Northwest Territories in 1999, Nunavut’s population is 85 percent Inuit, which is reflected in the region’s governance and priorities. Sovereignty for indigenous people, mineral rights, and questions regarding repatriation changed drastically with the shift in governance. The Terror and Erebus were British ships. They sank in Canadian waters. The land and water are now part of Nunavut. Who owns the ships, the hundreds of identified relics, and those that continue to be unearthed from Franklin’s and other expeditions located in the 350,000 square kilometers that comprise the region? “The situation is ongoing because the ownership of the ships, and the stuff on the ships, still hasn’t been clarified,” Craciun explains. “Inuit who’ve been on those waterways and land for millennia are now trying to have an equal say over negotiations about who these artifacts belong to. Can they leave Nunavut? Can they go to England? Those ships are still moving in a way.”

Craciun is experiencing a moment in time that is exceedingly rare for British literature scholars: her subject no longer resides exclusively in the mists of history. Instead, her polar research is butting up against the present, as the story of Franklin’s final journey is no longer static. In April 2018, Canada and the United Kingdom reached a significant agreement: the UK will retain 65 already salvaged Franklin relics, and the wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, along with any yet-to-be-discovered artifacts, will be formally transferred to Canada and the Inuit Heritage Trust. “The pieces of the ship, certainly artifacts from the ship, will keep traveling,” says Craciun. “They don’t just go from A to B. They continue traveling from the past through the present, and into the future.”

Craciun’s work now looks both back and forward in time, with her gaze steady on one of Earth’s most distant points—a place most often portrayed as wild, remote, and beyond the margins of the planet. But she has another way of thinking about the Arctic, its history and its people: “It’s all relative, and not peripheral. The Arctic is only peripheral if you’re here looking from Boston or London or Paris. If you reorient the world in a circumpolar way, it’s the center.”

The questions of proprietorship surrounding Franklin’s ships and their artifacts are reminiscent of repatriation controversies over the Rosetta Stone, the Elgin Marbles, and other relics purloined from where they were found. Craciun is pleased that Franklin’s ships will remain in Nunavut, perhaps with a museum to house them. “It’s interesting to see that material culture is always moving; there’s no natural logical neutral place for them to rest, ever, so we have to always make these decisions,” she says.

The breadth of material history can be mind-boggling, from the smallest seeds (Craciun is currently working on a book about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault), to the remains of the largest seafaring vessels and beyond. “Objects have distinct lives and now we speak of their biographies, not just their histories,” she says. “It’s humbling to trace what is called the social lives of objects. And to displace the centrality of human agency in their comings and goings.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.