Gotlieb Archival Research Center Celebrates the Bay State Banner

Half a century of photographs from Boston’s black newspaper

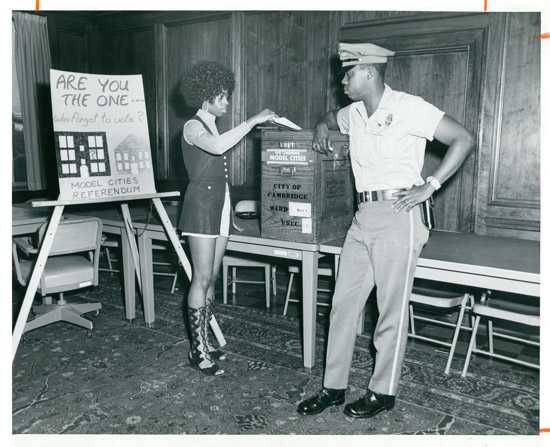

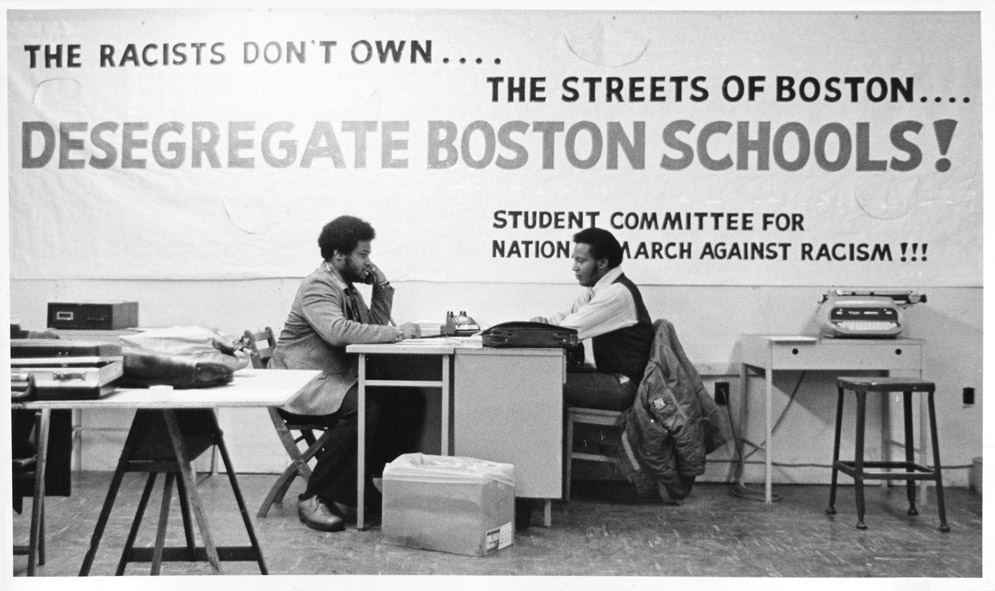

From its first edition in 1965, the Bay State Banner has chronicled the biggest stories in Boston’s black community, from Civil Rights era protests to the decade of conflict around the city’s school desegregation efforts and court-ordered busing to the election of Barack Obama to the presidency.

There were stories about the urban renewal programs that threatened to demolish swaths of black neighborhoods, policies that steered the city’s blacks to slum housing and subsidized tenements, and the efforts throughout by black activists to seize control of their community.

And Melvin B. Miller was there from the start.

“It was clear to me that you couldn’t possibly mobilize a group of people without there being a source of communication,” says Miller, who at 84 remains the Banner’s publisher and chief editor. “The Banner was supposed to elevate the people. And over the years, the Banner’s been an example of the best of black people.”

Photographs from the paper’s pages showing the political, educational, and economic struggles for racial justice in Boston over the last five decades are now on display in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center (HGARC) exhibition Boston Revisited: 50 Years of the Bay State Banner at Mugar Memorial Library.

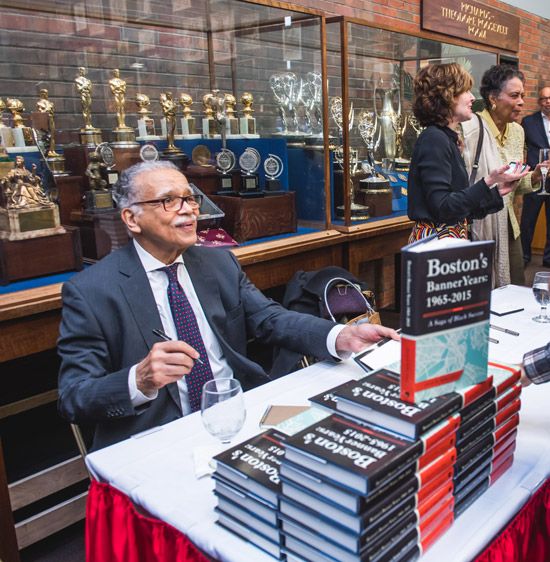

The exhibition includes hundreds of black-and-white newspaper images culled from the HGARC’s collection of more than 60,000 photographs. The exhibition coincides with Miller’s book Boston’s Banner Years: 1965-2015, A Saga of Black Success, a compilation of essays by current and former Banner staff about the city’s African American challenges and successes.

HGARC director Vita Paladino (MET’79, SSW’93) says the exhibition is not just a tribute to the Banner, but to Miller, a lawyer and devoted son of Boston whose storied paper has captured Boston history through the lens of race.

“I believe that we simply would not have the modern history of Boston’s black community, its people and neighborhoods, if not for Mel’s vision, his determination, and his relentless pursuit of excellence,” Paladino says.

Miller published the first edition of the Bay State Banner for Boston’s African American community just months after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. It was a tumultuous era of riots, protests, and demonstrations, but Miller, then a young US attorney, says new laws banning discrimination and ensuring voting rights and fair housing made him hopeful that the city’s racial crisis was coming to an end.

“Looking back after 50 years, it wasn’t quite so easy to accomplish,” says Miller, who says he’s frequently overoptimistic.

Sitting in his corner office at the paper’s Dorchester offices, Miller cuts a dignified figure, with his graying hair, sport coat, and ascot. A graduate of Harvard University and Columbia Law School, he says residents of Roxbury, the Boston neighborhood where he grew up, needed information that wasn’t coming from the city’s mainstream media. So he started the paper as a philanthropic effort while practicing law.

The inaugural edition was headlined, “What’s Wrong With Our Schools?” It looked at the substandard conditions of city schools attended by black students. Other editions reported on the dispiriting conditions in a housing project, hiring discrimination, and police use of force in the black community decades before those concerns became more widely recognized.

“We always had a professional idea of the importance of what we were doing in Boston,” he says. “If we didn’t do it, there would be a big information void.”

Miller’s nephew Yawu Miller, a Banner senior editor, says the paper also had a vital role in countering stereotypes of blacks mired in poverty or protest by printing images of smiling black faces at neighborhood block parties, parades, and community celebrations, which were an important part of its content.

The Banner also offered political role models with its coverage of black leaders, from Edward W. Brooke (LAW’48,’50, Hon.’68), a Republican from Roxbury who was the first African American elected to the US Senate since Reconstruction, through the presidency of Barack Obama.

Miller viewed the Banner as the successor to the Boston Guardian, the newspaper founded by early civil rights activist and fellow Harvard alum William Monroe Trotter, whose collection is also housed at the Gotlieb Center.

The Banner, Yawu Miller says, is “a military metaphor…a way to rally the troops.” He says his uncle “always saw the Banner in that light, as part of a fight to secure the rights of blacks in Boston and ensure that we all have the successes that anybody else has in the city.”

“There’s only one race. We’re all human.”

Melvin Miller’s demeanor is mannerly, however, rather than radical. The son of a postal service supervisor who got the job because of his score on the civil service exam, he learned the value of scoring well on tests to circumvent the racism he encountered in school. Yawu Miller says his uncle’s excellent SAT scores won him admission to Harvard.

Miller remains close to his roots and the friends of his childhood. He recalls a time before school segregation battles led whites to leave Boston in droves. The Roxbury of his youth was a middle-class community of different ethnicities and skin colors living side by side.

“I’m a Roxbury man,” he says. “I grew up in a family that thoroughly believed the whole concept of race is totally nuts. There’s only one race. We’re all human.”

Although he stepped down from his job as US attorney years earlier to run the Banner full-time, Miller continued to practice law. A BU trustee emeritus, in the 1990s he successfully represented Boston University during its efforts to retain the collection of papers and manuscripts Martin Luther King Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) left to the University when King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, wanted to have them relocated.

Miller donated the Banner collection to the University in 2014, adding to the depth of the HGARC holdings related to the Civil Rights era. Photographs on display include an undated photo of black businessmen inspecting a storefront spray-painted with “KKK” and a racial expletive, images from the decade of conflict over school desegregation and busing, as well as an iconic photo of James Brown’s performance in Boston after King’s assassination in 1968, which Brown agreed to have televised. Boston’s mayor credited Brown with helping to keep the city calm while rioting swept other cities in the nation.

In the Banner’s storied pages are images of anti-apartheid demonstrations and marches for youth jobs and scores of portraits of delivery drivers, restaurant owners, pastors, and churchgoers going about their everyday lives.

Keeping a community newspaper in operation for decades is no easy feat, particularly in the digital era, as the newspaper industry has experienced cutbacks and layoffs and print advertising revenues have shrunk. (The Banner has stopped publishing briefly twice—in 1966 and in 2009, when ad revenues dried up.)

Yet the Banner still stands. Miller says he feels hopeful that Boston and the Banner will continue thanks to a new generation of city leaders, an influx of diverse people interested in living in Roxbury, and the growth of the city’s black population, now one quarter of all residents.

“I’m going to try to find a way to keep it alive,” he says. “It has to move away from being narrowly racially focused. Being a true metropolitan paper—that’s our next step.”

The Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center exhibition Boston Revisited: 50 Years of the Bay State Banner is on view at the Mugar Memorial Library Richards-Frost Room, 771 Commonwealth Ave., Monday through Friday from 9:30 am to 4:30 pm; it is free and open to the public.

Megan Woolhouse can be reached at megwj@bu.edu.

This Series

Also in

Capturing History

-

February 8, 2018

Keeper of the Treasures

-

February 14, 2018

Love, Passion, and Longing Brought to Life

-

March 2, 2018

Oscars Up Close

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.