Lincoln in the Bardo Author George Saunders Reads at BU Tonight

Ha Jin Visiting Lecturer reflects on the craft, how to write with humor, the era of Trump

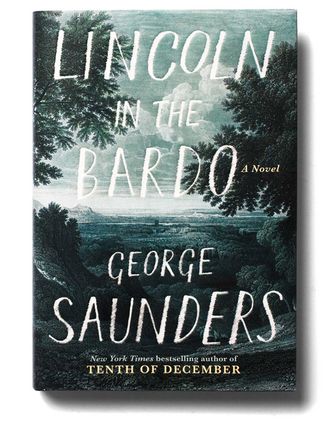

George Saunders was the author of four critically acclaimed short story collections when he published his first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, at 58. He’ll read from his work tonight at the Tsai Performance Center as this year’s Ha Jin Visiting Lecturer. Photo by David Crosby

Debut novels rarely earn the critical and popular acclaim that Lincoln in the Bardo did when it was published last year. Author George Saunders, 58 at the time, was no neophyte. He had written four well-received short story collections (CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, Pastoralia, In Persuasion Nation, and Tenth of December: Stories), each adding to his reputation for expertly blending realism with the surreal.

But a story that had captivated his imagination when he heard it decades ago led to his trying a new genre: in February 1862, President Abraham Lincoln’s youngest son, Willie, died at age 11 of typhoid fever and was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C. After his son died, the president visited the crypt several times. Some reports suggest he may have actually lifted the boy from his coffin and held him in his arms during the visits. The image of a grief-stricken Lincoln cradling his dead son stayed with Saunders, but he resisted writing about it, fearing initially, he told one interviewer, that he lacked “sufficient chops” to do the story justice. Eventually, a narrative began to form in his head, but he had no plans to make it his first novel.

In Lincoln in the Bardo, a group of spectral ghosts hovers as Willie is interred. Refusing to believe they are dead, these ghosts are unable to move on to an afterlife, trapped in a kind of limbo (what Buddhists refer to as the bardo). The ghosts act as a kind of Greek chorus, commenting on what they see when Lincoln returns to the cemetery, all the while musing on their own lives and longings. Together, they try to persuade Willie to move on to the afterlife, knowing that as a child, he’ll be consumed by demons unless he’s able to leave the bardo.

Lincoln in the Bardo proved to be both a popular and a critical hit, making numerous best-seller lists and earning the author one of literature’s most respected honors: the Man Booker Prize.

Tonight, Tuesday, October 9, Saunders will read from his book at the Tsai Performance Center for this year’s Ha Jin Visiting Lecture, an annual event sponsored by the Creative Writing Program.

“George Saunders is a great writer of our time,” says Ha Jin (GRS’93), a College of Arts & Sciences professor of creative writing, who has won several awards for his fiction. “His fiction is absolutely original, inventive in style, and zany in conception, and at the same time his stories are earnest, funny, often poetic. He is a genuine free spirit.”

BU Today spoke with Saunders about the challenges of writing fiction, the importance of humor in his work, and life in the age of Trump (his now-famous nonfiction piece “Who Are All These Trump Supporters?” was published in The New Yorker in 2016).

BU Today: You first heard the story of President Lincoln visiting his youngest son’s crypt more than 20 years ago, but resisted writing about it for years. Why?

Saunders: I couldn’t find a way in. There seemed to be no intersection between the sets of “what I can do” and “what this material needs.” My earlier work was very modern, almost sci-fi, dark, fast, ironic. How do you use that to tell this Lincoln story? But gradually, as I got older and wrote more, my range expanded. Also, living longer gave me a little more comfort with positive phenomena—happiness and love and functionality. Our kids grew up, and just being around them taught me that in this world positivity and hope do, or can, be rewarded. So that all meant that I had a growing confidence that the material that the younger me might have mishandled could, now, be handled. Someone once said “Happiness writes white,” and what he meant was that it’s harder, technically, to represent positive virtues in a compelling way. So I think I was working on that, all of those years.

What was it about this story that captivated you?

I actually don’t know. And speaking as a writer, I tend to not really care that much about why material interests me, but just that it interests me. I get a certain feeling about a topic or a voice and feel, ah, yes, I can do this. In that, it might be like love—if you found yourself insanely drawn to someone, I’m not sure you’d care much about why you were.

Prior to this book, you were best known as a a short-story writer. Had you avoided writing a novel on purpose?

No, but I had tried and failed a few times. I wrote one big novel that was no good, and several shorter novels that kept shrinking until they were stories. So I had pretty much (and happily) given up on writing a novel until this one came along, and even then I tried to resist it—kind of kept saying, you know, if you want to be a story, please do.

When you began writing Lincoln, did you know it would be a novel or did that emerge later?

No, I was trying to keep it as short as possible, but then, gradually, it sort of proved itself. By which I mean, I got to about page 60 and it was as tight and fast as I could get it, and I looked up and I’d only told about a fifth of the story.

Did you have any trepidation about working in another genre?

Yes, I did, and I think that was important. In any artistic venture, it’s good to be terrified—to really feel the potential for fiasco. And the “craft” is really just doing whatever keeps you away from fiasco. Like if someone asked you, “Do you have any fear riding that unicycle near that cliff?” your answer should be, “Yes, of course!” That is my craft: being sufficiently afraid. But in writing, you have to be sufficiently afraid and joyful at the same time.

The novel has a remarkably innovative structure—a blend of realism and the fantastic, a collage-like quality that blends a Greek chorus of ghosts commenting on the action with quotes from historical sources and invented bits. How did you arrive at the structure?

Thank you. Most of these artistic “decisions” happen by trial and error—the aforementioned “trying not to ride your unicycle off the cliff.” With this material, the big danger was its historical nature. That had a high potential to be both sad and boring, a bad combo. Like going to a funeral with a very slow-talking priest. So, the challenge was to find a way to take on that material and keep things fast and weird and, again, somewhat joyful, i.e., exuberant. Once I stumbled onto that particular form, things felt fun and doable, if that makes sense.

The novel is an exploration of grief and loss, but also has a lot of humor, which figures prominently in much of your fiction. Can you talk about that?

I think it’s because it figures pretty heavily in my approach to life. For me, it was a big breakthrough moment when I figured out that if you live by a certain virtue, it should probably be in your art. I was always joking—to get out of trouble, charm somebody, ease a tense situation. The only time I had no humor was when I was writing. Philosophically, I think life is pretty funny. I mean, it’s funny that we think we’re permanent and…we die. Funny that we think we’re at the center of the universe, the star of the show—and then a ladder falls on us and causes us to fall on the ice and as we go down, we fart. Funny! And the whole school is watching. And so on. And no—that example is not from my personal experience. There was actually no ladder that caused me to fall.

Are the challenges of writing a short story the same as writing a novel or are they different?

Both. The basic challenge is the same: shaping the current section so that it gracefully produces, or relates to, the next. But different in the way that you plan. With a story, I try not to plan at all. With the novel (or at least this one), I had a very loose outline to which I could refer if I got lost.

What surprised you most in writing the novel?

The way that, without me asking them to, all of the characters started cooperating to get Willie out of there. I didn’t see that coming—that “viral goodness” that they started enacting.

How do you approach a story?

Mostly I just work a sentence at a time, trying to make it charming and truthful. Then that thought will produce ideas for the next sentence. I once had an editor who, when I asked him what he liked about my story (he’d been editing in such a way that I assumed he didn’t like much about it), said: “Well, I read a sentence…and I like it…enough to read the next.” That seems like a very wise summation of the whole craft. You can’t get “theme” and “character” or “political meaning” unless your reader keeps reading.

You’ve said that revision is enormously important as you shape a story. Can you explain?

I think a work of fiction is really just a system upon which the writer has expressed her preferences over and over, even to the level of the phrase. When someone chooses and re-chooses, over and over, in thousands of different states of mind, over many months or years, some essential mark gets put on it—the story is more like the writer than the “everyday” writer-person. That’s revision. Really, it’s a form of taking absolute responsibility for your story.

You bring a great deal of empathy to your fiction. Is that an essential quality for a writer?

Well, empathy can be a form of attention—the writer is paying attention to the text, to the character, and (most of all) to her imagined reader. But the actual story produced might be quite snarky or naughty or dark on its surface (see, for example, Flannery O’Connor or Gogol). So I think the main responsibility of the writer is to be vivid and entertaining and truthful and efficient—the “meaning” of the story will conform to you, as a person, if you revise with gusto and try to keep your reader reading. One person’s form of “empathy,” or “love,” on the page, might (and should) look different from another person’s. Think about how many styles of friendship from which you’ve benefited in your life—teasing, protection, truthfulness, etc.

Having now written a novel, do you think you’ll go back and forth between short stories and longer fiction?

I hope so, but I think, for me, the main thing is to see what I feel like doing in the moment—not to “decide” much about future work, but to see what feels most alive. Right now I’ve just got one story going—that is causing me a lot of trouble and a lot of fun.

You wrote an article about Trump supporters for The New Yorker in 2016, before the presidential election, that garnered a lot of attention. What did you discover in your reporting that you hadn’t expected and what has surprised you since?

At that time, nobody thought Trump would win, and I was surprised at how passionate his supporters were and how aggrieved. It was like they were hearing some frequency I couldn’t hear, and it was really pissing them off. Now, I can see that I was ignorant as to how much fear there was in our country and also how much residual “racial nostalgia” we have going on here. I’m still trying to understand the whole thing and have resolved to stop wailing and gnashing my teeth and to go ahead and take responsibility for my failure to fully understand my own country—I’m a writer, that’s what I’m supposed to be doing. But I am looking at the United States differently now—trying to keep loving the beautiful and generous elements of it while also realizing that we’ve always had a core of violence and racism and misogyny and homophobia and that we built up so much of our wealth stealing other people’s labor and land. All of these things are simultaneously true. We’re nice! We fought like hell to keep slavery alive! Our land is so pretty! It didn’t use to be ours, but then we took it, by killing women and children as needed! Our shows are so funny! We’re great at jazz! We’ve treated women badly forever! Montana is so beautiful! We made gay and lesbian people feel ashamed since Day One! Most of us love this place so much and, while traveling, get homesick for it!

One thing fiction trains us is allowing two or more truths to exist at once, without flinching or becoming distraught. It’s really a very high form of beauty, when Truth A and Truth B and Truth C are all standing there, contradicting each other and refusing to let you relax and go on autopilot, especially if we can manage the courage to stand there among those Truths, becoming wiser every minute by abiding in their presence.

The country seems more divided now than ever. Do you imagine that changing at any point in the near future?

I do, because it’s intolerable and it’s making everyone sad. Also, I’d suggest that these divisions are more virtual than real. (They’re starting to leach out into the real, yes, but…) If you go to a baseball game or the mall or your car breaks down, you’ll notice, generally, that we’re still pretty good to each other. People are especially rude and emboldened and sure of their own complete rightness on the internet. To me, that suggests that the internet is something we need to think a little more about. If someone is raging against me on Twitter and I never read it—are they raging against me? Not to me, they’re not. So, not to sound like a Luddite, but I predict that in 20 years or so, people are going to be like, “Why did they spend so much time online and why did they believe that crap was real?” “Why were those invented/exaggerated versions of themselves fighting so harshly with those invented/exaggerated versions of those other people to whom, if they met in real life, they would be completely polite?” And they’re going to say, “Jeez, those poor dopes made themselves so unhappy and agitated.” And: “They could have been outside, looking at the trees, which were these beautiful biologic structures that have now burned away because of global warming.”

You have taught for more than two decades in Syracuse University’s MFA program. What advice do you have for young writers?

The main thing is: learn how to revise. That skill is what separates the real writers—who publish and use writing all their lives as a way to become more expansive people—from the amateurs, who think that “writing well” means “getting it right the first time.”

George Saunders, this year’s Ha Jin Visiting Lecturer, will read tonight, Tuesday, October 9, at 7 pm, at the Tsai Performance Center, 685 Commonwealth Ave. The event is free and open to the public and will be followed by a Q&A and a book signing.

The Ha Jin Visiting Lecture series, made possible by a gift from former BU trustee Robert J. Hildreth, brings internationally renowned fiction writers to BU to teach master classes and give public lectures. The series is named for award-winning novelist Ha Jin, a CAS professor of creative writing.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.