Drawing Out the Punch Line

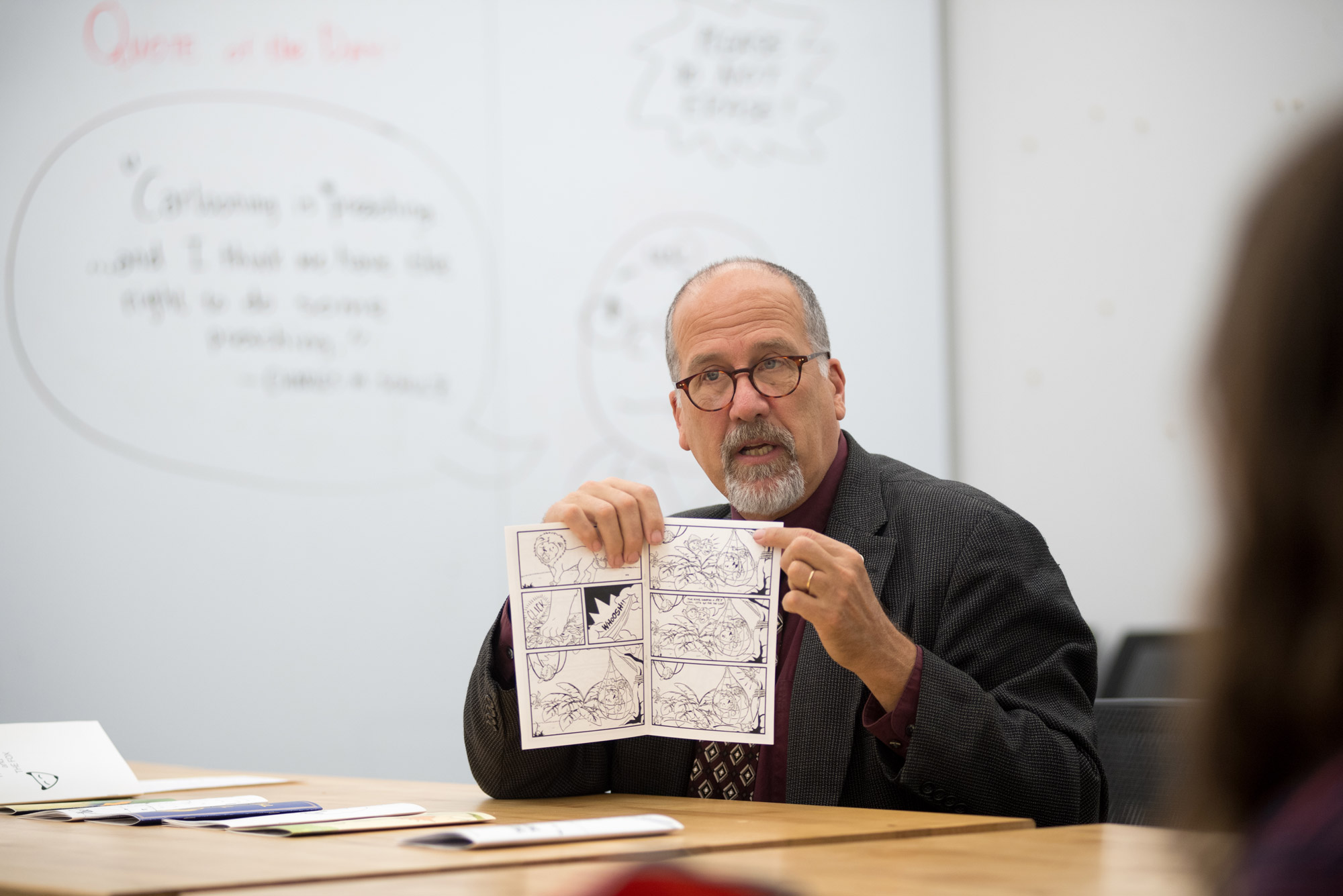

Paul Karasik teaches “drawing into animation” at the College of Fine Arts and will speak about his career, which includes graphic novels and cartoons in The New Yorker, tonight at WBUR’s CitySpace.

Drawing Out the Punch Line

CFA lecturer Paul Karasik to speak about his career in comics tonight at WBUR’s CitySpace

Comics fans might think that publishing gag cartoons in the hallowed pages of The New Yorker would be the apotheosis of a career. Paul Karasik has a lot more going on.

“Most cartoonists in the history of cartooning are notable for creating one character or one comic strip or working for one comic book company for their lives, doing the same thing every day,” says Karasik, a College of Fine Arts School of Visual Arts visiting lecturer, sitting in his classroom at 808 Comm Ave recently. “The great cartoonist Ernie Bushmiller [Nancy] started being a cartoonist when he was a teenager and died in his studio with his pen in his hand at age 82. I could never do that. It’s just not in my temperament, and my skill set is more varied than that.”

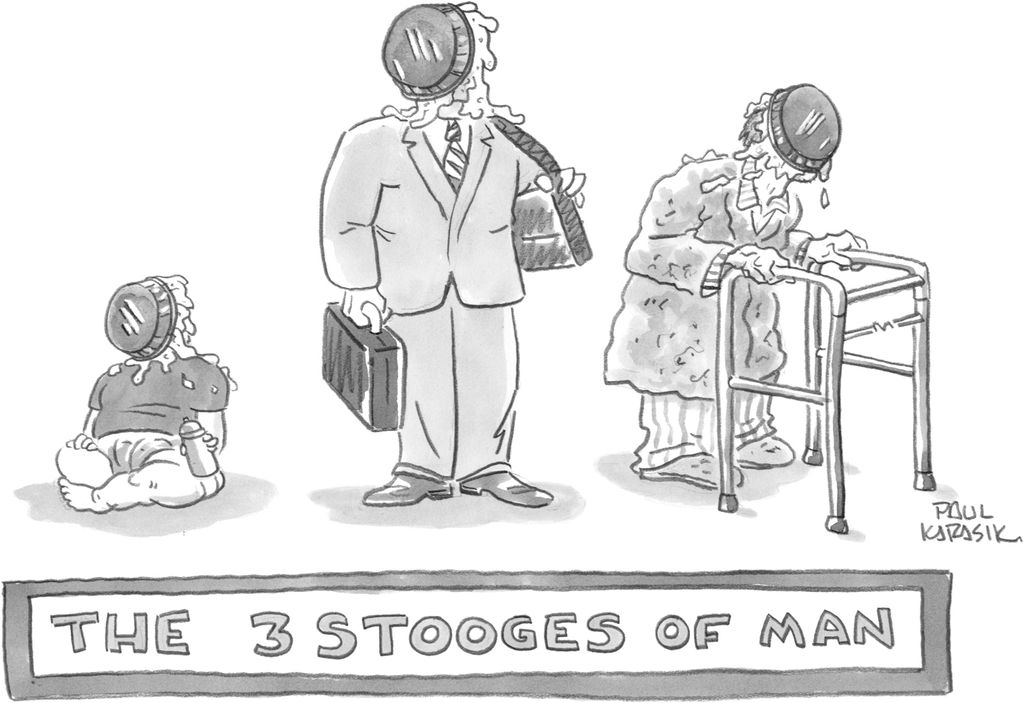

Karasik publishes single-panel gags in The New Yorker, but he’s probably best known in the world of comics for cocreating, with David Mazzuchelli, the graphic novel adaptation of Paul Auster’s book City of Glass, named by Comics Journal as one of the Best Comics of the 20th Century. With his sister, Judy Karasik, Karasik created The Ride Together, a Brother and Sister’s Memoir of Autism in the Family, winner of the Autism Society of America Best Literary Work of the Year. He won his second Eisner Award (given annually for creative achievement in American comic books) last year for How To Read Nancy, a scholarly book about Bushmiller’s work and the language of comics, cowritten with Mark Newgarden.

After earning a degree in graphic design from the Pratt Institute, Karasik studied at the School of Visual Arts in New York City when comic giants Harvey Kurtzman, Will Eisner (for whom the Eisner Award is named), and Art Spiegelman were on the faculty.

Cartoon courtesy of Condé Nast

At BU this semester, Karasik is teaching the course Drawing into Animation, intended to guide students through storyboarding and scripting, from informal sketches to full narrative graphic novels. The dozen students’ multi-panel “how-to” comics, some helpful, some funny, and some both, are on display outside his classroom. (He also teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design.)

Karasik will discuss his career Friday, November 8, at 6:30 pm, at WBUR’s CitySpace, in an event called Under the Influence of Comics: A Look Back with Paul Karasik. In this illustrated lecture, he’ll describe how his reading of comics shapes his making of comics.

“People will get a glimpse at a different way of being a cartoonist,” he says. “And there’s a little bit of backstage-at-the-comics, where I will show specific images that influenced my thinking.” BU Today spoke with Karasik about his work and his CFA class.

Q&A

With Paul Karasik

BU Today: It’s hard to square someone doing single-panel New Yorker cartoons with publishing a memoir like The Ride Together.

Karasik: Because I’m such an odd duck, it’s really difficult for people to grasp who I am or what I am. If I go to a cocktail party and someone asks what I do and I say I’m a cartoonist and they say, “Oh, have I seen your work?” I’m not going to tell them I did a memoir and an adaptation: their eyes kind of glaze over. But if I tell them I have cartoons in The New Yorker, suddenly they’re pouring me a glass of wine and handing me the keys to the Bentley, because everybody knows what that is.

Like the rest of the newspaper industry, comic strips are having a hard time now. How is the cartooning business in general?

Practically speaking, it’s next to impossible to make your living as a gag cartoonist for The New Yorker. Back in the day, in the 1960s, you could take your portfolio around to any one of a dozen magazines, starting with The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post and working your way down to some cheap men’s magazine. You could bring home the bacon. But now gag cartooning is virtually a dead art form. The New Yorker is really the last bastion.

You worked at Raw, the groundbreaking magazine run by Art Spiegelman and his wife, the artist Françoise Mouly. What was that like?

My work ethic improved. Anything really of any lasting merit takes some hard work. Even the most spontaneous action is precipitated by thought and practice. The most important thing, though, was that the formal aspects of comics can be manipulated by the artist to communicate deeply personal ideas and thoughts and experiences. It’s more about the thinking—about manipulating the language of comics—than it is about being able to draw pretty pictures.

How does your CFA class work?

It’s heavily weighted on the process of making comics and the language of comics and less on the product. So in their drawing class or painting class, the students might get an assignment one week and turn it in the next week and get the next assignment. My assignments go on for weeks, as students take their ideas and brainstorm them, thumbnail them, script them, sketch them, re-sketch them, re-re-sketch them, pencil them, ink them, tweak them…and eventually come up with a series of mini-comics they’ve done throughout the semester. Process is where the learning takes place. I just teach the way I know how to work, which is based on an understanding of the building blocks of comics.

It’s about how those building blocks are assembled?

I realized at some point that my training in graphic design at Pratt Institute actually came in very useful as a cartoonist, because half the job of a cartoonist is to direct the reader’s attention in a very specific way. You’re taking the reader on a journey. Whether it’s a multipage graphic novel or a single gag, you’re still taking the reader on a very specific, eye-controlled journey. My gag cartoons are very far from slapdash. They’re very tightly composed, with things revealed to the eye in a certain order.

Can you give an example—one thing people should look at the next time they pick up the comics?

The next time you look at any piece of art, whether you go to the MFA and find a painting you like or you open The New Yorker and find a gag you think is particularly clever, rather than turning the page or going to the next gallery, stop and look at it for twice as long as you normally would. Spend five minutes just looking at it and figuring out how it works. Try to disassemble it into its separate parts. Abstract it and look at the various units of information, the various objects that are being depicted in any picture pane. See how they’re depicted and what emphasis is being placed on them. It sounds like a clinical approach that would take the joy out of it. But I personally find it really illuminating to deconstruct a work of art you’re touched by. It will get you in closer to the reason you like it. And it will enrich your life, because it will put you closer in touch with who you are.

What’s next for you?

I’ll be spending the spring semester as a visiting professor at Texas A&M. There is a professor there who is interested in eye tracking, and we’re going to run a series of experiments on how comics and comic strips are read. I’ve been teaching for years under the supposition that comics are read in a certain manner, but it’s just empirical, based on my own experience. So I want to see if we can actually determine how specific examples of comic art are digested by the eye. When does the mind make the connection between the image and the caption to create synthesis that produces understanding?

Are you going to be back at BU next fall?

I hope so.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Event Details

Under the Influence of Comics: A Look Back with Paul Karasik

Purchase tickets ($10) here. The event is in partnership with the BU College of Fine Arts School of Visual Arts.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.