New Book by BU Sociologist Ashley Mears Explores the Conspicuous Leisure of the Wealthy and Famous, Mostly Men

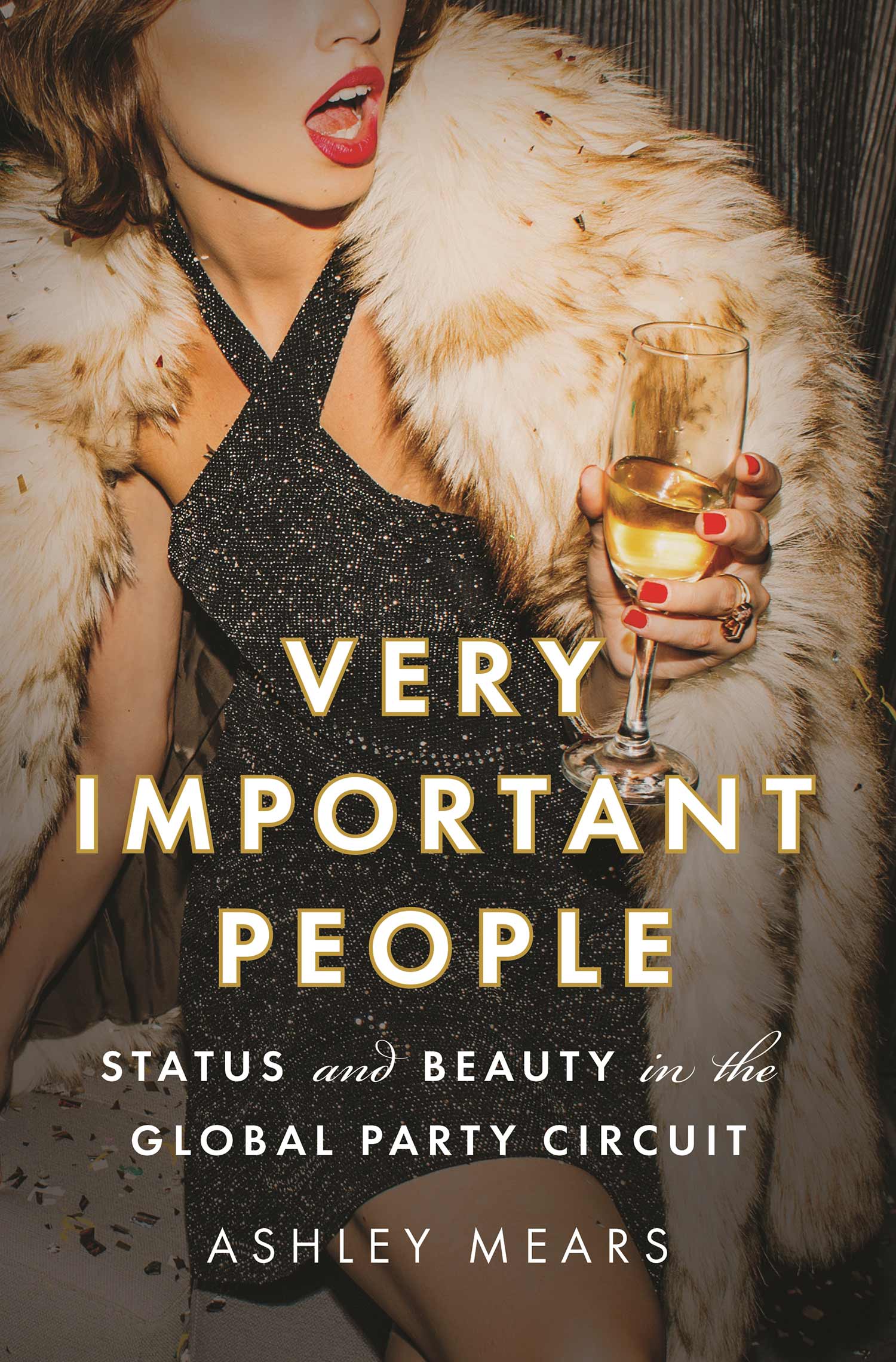

In her new book, Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit, Ashley Mears, a CAS associate professor of sociology, shows how conspicuous leisure is “built upon a gendered economy of labor in which women’s bodies are assessed against men’s money.” Photo courtesy of Ashley Mears

New Book by BU Sociologist Ashley Mears Explores the Conspicuous Leisure of the Wealthy and Famous, Mostly Men

Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit is a study of the over-the-top consumption among the new global leisure class

There’s more to “models and bottles” than you might think. When it comes to the global party scene, a debauched night at a club is anything but spontaneous, reveals Ashley Mears in her latest book, Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit (Princeton University Press, 2020). Chronicling Mears’ 18-month dive into the world of exclusive nightclubs and the people who profit from them (read: almost exclusively men), the book peels back the layers of Dom Perignon, drugs, and beautiful women that make hotspots from Manhattan to Cannes tick, exposing a complicated, worldwide network of rituals and players that would have any sociologist itching to write about it.

And that’s exactly what happened to Mears, a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of sociology. A former teenage model, she was introduced to the global party scene as an NYU graduate student studying another notoriously exclusive world—the modeling industry—donning stilettos and returning to the catwalk for her PhD dissertation. That research became the subject of her first book, Pricing Beauty: The Making of a Fashion Model (University of California Press, 2011).

For Very Important People, Mears used her model contacts and stature to become a “girl”—one of the young, tall, and attractive women that nightclubs revolve around—this time shadowing club promoters, owners, high rollers, and “girls” in order to document the economics of excess in hotspots like Miami and the French Riviera.

The book is a study of conspicuous consumption among the new global leisure class, showing, Mears says, “how conspicuous leisure is built upon a gendered economy of labor in which women’s bodies are assessed against men’s money.” She says that while the book critiques the structures that maintain economic and gender inequality, it also “outlines women’s agency and the seductions of inclusion in the exclusive world of elite consumption.”

BU Today talked with Mears about her time moonlighting as a party girl, what club promoters actually do all day, and how exploitation functions best when you’re having fun.

Q&A

With Ashley Mears

BU Today: How did the idea for this book come to fruition? Why nightlife?

Mears: I didn’t see it as a study of nightlife in the beginning. But nightlife is a great case to examine consumption dynamics among economic elites. And [the idea began] in the context of the great recession of 2008, when I was seeing news reports on how bankers were recklessly spending money while we were in a global financial retrenchment. It was also a time when Occupy Wall Street was still really prominent, and not far from the Occupy Wall Street protestors in Manhattan were these clubs catering to really rich people—people who spend huge sums on price-inflated bottles of alcohol that they then destroy in ritualized consumption forms. I became really fascinated by how that level of ostentation was possible in that moment.

I knew so many people who worked in the clubs from some of my earlier research, when I was connected to the fashion modeling world. So from those contacts, I was able to get a foot in the door and start spending time consistently out in these places and getting up close.

What did your research involve?

The fieldwork for this was actually pretty arduous. The work that I do is a certain type of immersive ethnography, sometimes called “participant observation,” where a researcher takes on the role of the people they’re studying in order to better understand their worldview. I got a fellowship from the BU Center for the Humanities in the spring of 2012 that brought me out of teaching temporarily, so I moved back to New York and got a tiny bedroom in Williamsburg, on the L train.

At that time, the L went straight across Manhattan and put me in the Meatpacking District in about 15 minutes. And so basically, I would go out about four nights a week, or more if I could. [A typical night] begins with a group dinner with promoters that starts at around 10 pm. Then we would go to the club by around midnight, and stay till about 3 am. And then there might be an after party. Because I took on this role of being a girl, it was expected that I would wear these very high heels every night and keep these nocturnal hours. So that’s what I did. And then during the day, I tried to keep pace with the promoters by following them and hanging out with them. And I ultimately followed them to the Hamptons, Miami, and to Cannes and St. Tropez in the French Riviera.

What does a promoter do all day?

One promoter told me that “there can be no nighttime without the day.” During the day, promoters are currying favors and building relationships with the girls, doing things like driving young models to their castings and taking them out to lunch, so that they’re in a better position to leverage the social connection and intimacy in order to get the girls to come out. There’s this really interesting work of balancing economic interests with friendship [because promoters are paid to bring women to the clubs]—promoters will use the language “Come support me out at the club,” as opposed to “Come let me profit off you.” And so a lot of the fieldwork was just seeing how that plays out and doing interviews with different promoters. I would interview them, sometimes several times, and then go out with them.

Exploitation works best when it is enjoyable and it feels like a relation of authentic friendship.

What makes someone a successful girl?

That’s kind of an oxymoron. The ideal girl is somebody who looks the part [who is or could be a model: young, attractive, and at least 5’10”]—who enjoys going out regularly and doesn’t have any other commitments. No job, no boyfriend, no personal network, nothing like that. She shouldn’t have her own economic means to pay for herself; if she did, she’d be less motivated by all the free drinks. A newcomer to New York as a fashion model would be a great candidate for a promoter looking to expand his pool of girls.

That sounds just like trafficking…

Well, it is trafficking in the way that anthropologists originally defined it. Trafficking in women has historically been really important for forging alliances between men who control kinship systems. Women have often been used as a way to forge alliances through things like marriage, and for men to reap profits. And so this isn’t headline-grabbing sex trafficking, but it is trafficking. Forms of trafficking are around us all the time.

“Exploitation works best when it is enjoyable and it feels like a relation of authentic friendship,” you write. Can you elaborate on that, in terms of the relationships between the promoters and the girls?

In saying that, I’m drawing from a lot of other social research that shows that in the workplace, people tend to respond better when they’re feeling valued and the work is meaningful. It’s a lot of work to be a girl, even though girls are unpaid. In this case, everything goes much more smoothly when the girls believe that the promoter is their friend. They’re much more likely to tolerate any number of inconveniences or even risks to support a friend, rather than add value to a boss.

And I think that this complicates the way that a lot of people think about inequality, with people conflating objectification or exploitation with the idea that it must be uncomfortable or painful. And at a structural level, yes. But also, people oftentimes consent to relationships or practices that work against their favor because they believe in it, or because there’s some other symbolic or social benefit. And I think that we have to take those situations seriously if we want to get to the bottom of questions like, why do people continue to do things that don’t work in their own interest? Because they’re trying to protect some kind of symbolic value.

So, what is the value here?

Something people will say is, “This sounds awful—how could anybody have fun doing this? Is it actually fun?” And, yes, it is! That’s one of the main reasons why people participate in nightlife. Because they like the music at the clubs, they like the vibe, they like the fact that it’s exclusive, and that they get to be inside, in this exclusive world. So there’s an ego stroke of being included. Being close to so much wealth and power, and being able to photograph that and put it on Instagram. There’s so much symbolic value and pleasure that people gain from being in these worlds. But it’s hard to explain that to people.

What were the most fun moments for you?

There are two moments that were back-to-back, in Cannes. I was staying in this villa with dozens of other girls that were going out with this team of promoters. One night, a big hip-hop artist was coming through to perform at one of the clubs, and everybody was so excited—people were dancing on top of the tables and fireworks were going off everywhere. When the club closed at four, everybody went home to the villa, where people were still dancing on the coffee table and partying. Everyone went to bed at like 6 or 7 am. I mean, there can be these moments that are just wildly fun, where you really do feel like you’re included in something special. So that night was incredible.

And then the next day was also amazing for the complete opposite reason. Everybody was so exhausted and hungover that people were literally falling asleep on the sofa at the club that night. The promoter that I was with actually disappeared for a few hours to go take a nap.

What are some of the crazy things you saw during your fieldwork?

I’ve seen people shake and spray their bottles of champagne in a champagne shower, or champagne fight. One night, I was in Miami at Ultra, an electronic-music festival, and I saw somebody buying trains and trains of Dom Perignon. I was told that it was about $200,000 worth of champagne. That night, people weren’t even drinking from glasses—they were just holding their own bottles of Dom, carrying on. You could look at each bottle and be like, “Wow, that’s a huge chunk of my rent money!”

Finally, why are we so fascinated by this world most of us will never have access to?

A lot of people would describe this world and the indiscriminate spending as ridiculous, which is a term that captures both humor and disdain. But it’s kind of like a car crash, where you can’t look away.

And then there is this fascination with entering the lives of the rich and famous, seeing what people spend their money on, like their gold-plated bathrooms or whatever. It might also be a way for people to fantasize—if you had no resource constraints, what would you do? How would you organize your life?

At the same time, we’re in a historically significant moment of vast economic inequality, both in the United States and around the world. And so it’s really important that we understand more about the lifestyles and worldviews of the rich, as well as the cultural assumptions they’re making, because they yield so much economic and political power right now.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.