In Hunting Whitey, COM Alum Casey Sherman and His Coauthor Detail the 16-Year Hunt for the FBI’s Most Wanted Man

One of the last known photographs of Whitey Bulger (left) in Boston before he became a fugitive shows him strolling with confederate Kevin Weeks in 1995. Evidence photo courtesy of United States Attorney

COM Alum Casey Sherman’s Book Has New Details on Whitey Bulger

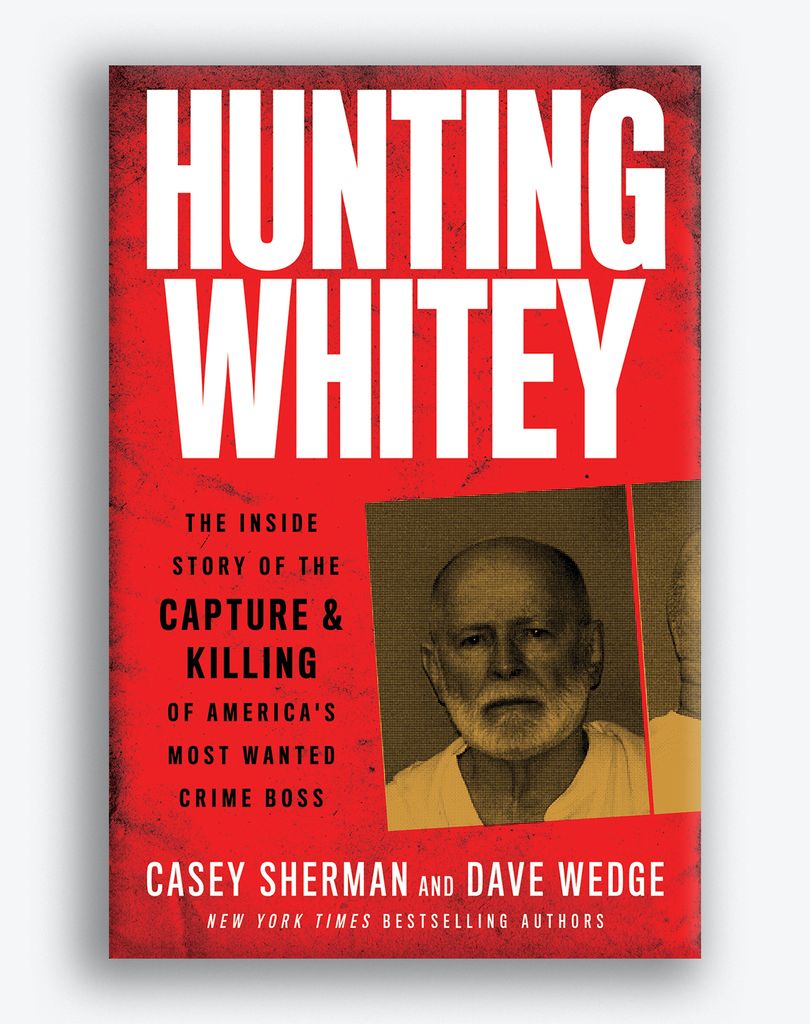

Hunting Whitey, cowritten with Dave Wedge, taps trove of gangster’s letters

In 2006, 11 years into James “Whitey” Bulger’s life on the lam, San Diego sheriff’s deputy Rich Eaton went to see The Departed, the fictionalized movie about the Boston gangster who topped the FBI’s Most Wanted List. As the theater lights darkened, Eaton, a Massachusetts native, caught sight of a man four rows away—and caught his breath.

HarperCollins

“Is that Whitey f—ing Bulger?” he thought, according to Hunting Whitey: The Inside Story of the Capture & Killing of America’s Most Wanted Crime Boss (William Morrow, 2020), the new book cowritten by Casey Sherman (COM’93). After the film, Eaton and the suspect locked eyes in the lobby, and the lawman was convinced. Lacking a gun and seeing Bulger’s bulging under his shirt, he watched his quarry board a trolley, then retrieved his weapon from his nearby office. He and a partner hightailed it ahead of the trolley to its station, only to find Bulger had hopped off and escaped.

The near-capture of the man who’d inspired the film—murderer, longtime leader of Boston’s Winter Hill Gang, and an FBI informant, who fled in 1995 after a corrupt federal agent tipped him that the law was closing in—is among the revelations in Sherman’s book, his fourth with coauthor Dave Wedge and one that takes on a mythological Boston figure.

The “sociopathic” Bulger loved animals, but murdered humans like flies, the authors write, and was finally arrested five years after the theater encounter. Convicted on racketeering and 11 murder charges (prosecutors said he’d actually murdered 19 people), he landed in a West Virginia penitentiary. On his first day there in 2018, he was beaten to death with tube socks stuffed with padlocks, targeted by an inmate who knew Bulger had framed a man for murder and had been an informant.

“We do our best to deconstruct the mythology around Bulger,” says Sherman, whose eclectic oeuvre of books covers topics from Tom Brady to the Boston Marathon bombings. “I lived in Southie in the early 1990s”—Bulger’s Boston base, where many idolized him for his reputed generosity—“and had seen Whitey on occasion in the neighborhood. He was no Robin Hood–style figure in South Boston. He was a cold-blooded killer of both men and women. He did not keep drugs out of Southie as legend has it. He pumped endless amounts of cocaine and heroin into South Boston, nearly killing off an entire generation of young men and women who became hooked on his product.”

Sherman spoke with Bostonia about Bulger, his suspected killer, and the crisis in the US prison system.

Q&A

With Casey Sherman

Bostonia: Can you describe some of the heretofore unreported information you and your coauthor dug up, and how you found that information?

Casey Sherman: We had exclusive access to 70 letters that Whitey wrote in his own hand, including his own description of his capture. Bulger learned how to become a fugitive by reading books and learning new technology to gain access to Social Security numbers that would allow him to obtain phony identification cards. However, Bulger was willing to gamble with his freedom. We learned that he would take long drives from southern California to the Midwest just to call his family.

We also received unprecedented access to the FBI’s investigation, and I interviewed all the key agents that were instrumental in his capture. We are the only journalists to have successfully corresponded with the suspected killer of Whitey Bulger, a convicted mobster named Fotios “Freddy” Geas. Geas has been writing us letters with rubber tipped pencils from solitary confinement. They do not allow him anything sharp to write with for fear that he’ll jab himself in the neck or try to kill a guard.

You make clear the decision to transfer Bulger to West Virginia was his death sentence. Does your reporting leave you thinking this was incompetence by federal officials? Indifference to Bulger’s fate? Both?

Our research shows that Whitey’s murder was not the result of some vast governmental conspiracy to silence the aging gangster. It was, however, the result of unlawful blindness on behalf of officials in the Federal Bureau of Prisons. After making a threat against a prison nurse in Florida, Bulger, whose rapidly deteriorating health was mysteriously upgraded, was sent not to a medical facility, but to Hazelton in West Virginia, the most notorious prison in America and nicknamed “Misery Mountain” for good reason. It’s likely that the warden in Florida didn’t believe Bulger would last very long there, and he didn’t.

Should we care about how Bulger died, given that, as you write, “he was responsible for his own death. It was gangster karma”?

We should care how Bulger was killed because it speaks to a larger crisis happening right now within the Federal Bureau of Prisons. The environment there is like Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. It’s complete anarchy, and the wardens answer to no one but themselves. For every Whitey Bulger, there is someone who’s been wrongfully convicted or convicted of a nonviolent crime that ends up dead in their cell. That is why reforms need to be made.

HarperCollins

Your book shows the FBI had both scoundrels—the crooked agents who were mixed up with, and helped, gangsters like Bulger—and heroes, the dedicated law enforcers who tracked him down. Could this happen again—could a law enforcement agency like the FBI be so corrupted today?

We’d be naive to think that it couldn’t happen again inside any branch of law enforcement. But what I love about this story is that the FBI persevered beyond a very painful and shameful period to finally set things right, through a new breed of agents who were determined to capture him.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.