CTE, Contact Sports Play Linked to REM Sleep Behavior Disorder

CTE, Contact Sports Play Linked to REM Sleep Behavior Disorder

BU researchers have discovered the disorder, which causes people to physically act out dreams while still sleeping, occurs in a third of contact sports athletes with chronic traumatic encephalopathy

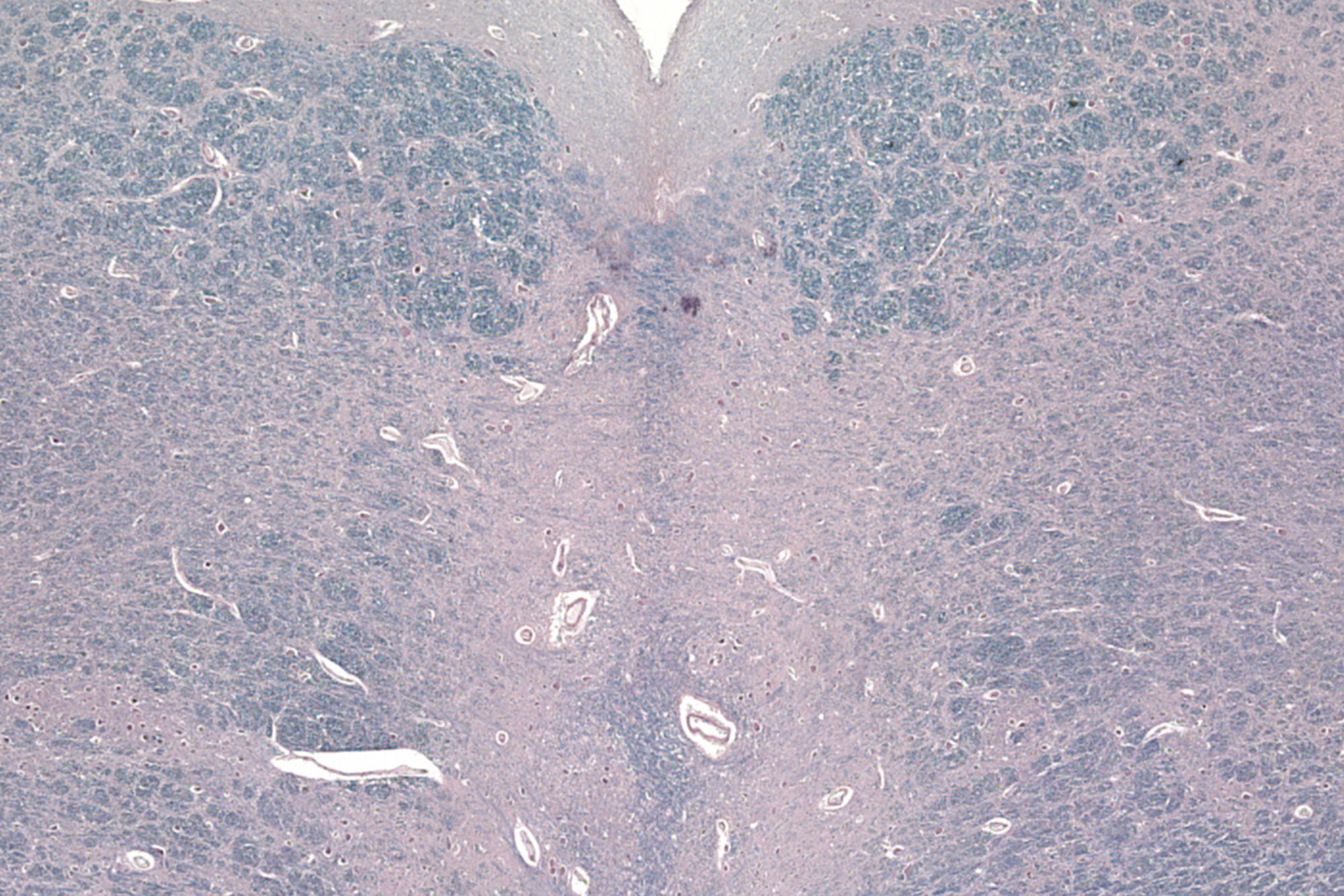

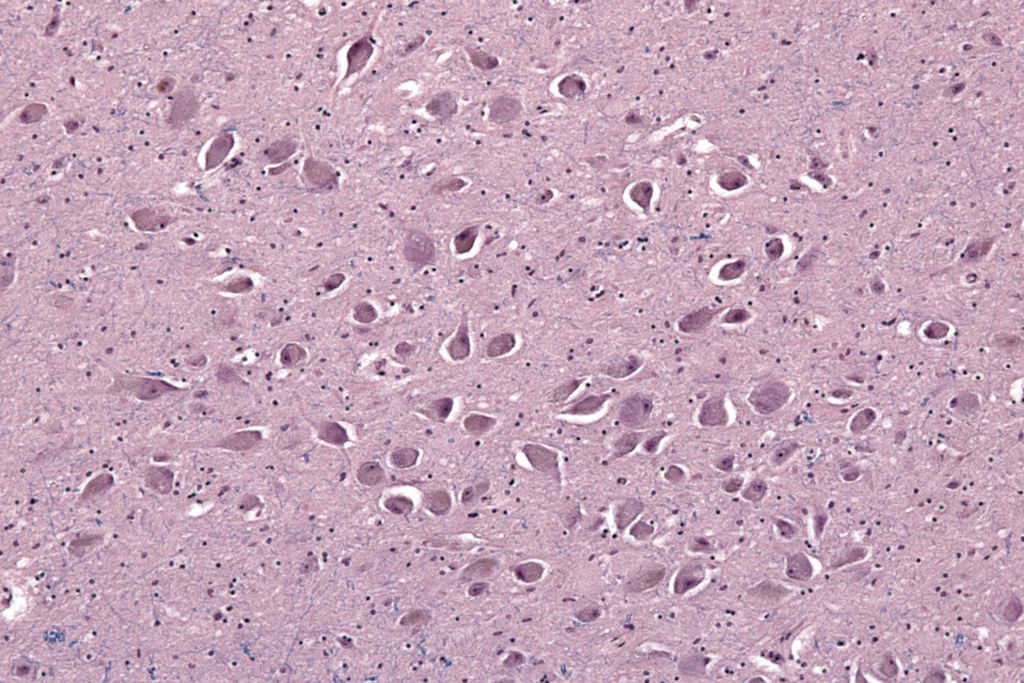

BU chronic traumatic encephalopathy researchers looked closely at the brain tissue of contact sports athletes with CTE, examining a part of the brainstem (seen here under 100x magnification) containing clusters of neurons that play a critical role in the brain’s ability to regulate sleep/wake states. Credit: Stein, et. al

Researchers at Boston University have found a link between chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a devastating neurodegenerative disease associated with repetitive head impacts, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder. The disorder, typically associated with Parkinson’s disease, interrupts or disturbs sleep paralysis during REM sleep, when most dreams are experienced. The lack of paralysis causes sleepers to act out vivid and often disturbing dreams by talking, flailing their arms and legs, punching, kicking, grabbing, and more.

“It’s a very rare disorder,” says BU neuropathologist Thor Stein. “Dreams can have very high emotional content, and when a person wakes up thrashing about, they’re really disturbed.”

Although some individuals diagnosed with CTE after death were reported to suffer from sleep dysfunction, the type of disorder and its cause has never been formally explored. Now, in a new study published today in the journal Acta Neuropathologica, Stein and a team of researchers report that 32 percent of contact sports athletes with CTE had experienced REM sleep behavior disorder during their life. Only 1 percent of the general population has the disorder. It’s the first study to connect repetitive head impacts from playing contact sports with the sleep disorder.

“We didn’t expect to find this disorder as frequently as we did [in athletes with CTE],” says Stein, a neuropathologist at VA Boston Healthcare System, a BU School of Medicine assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine, and the corresponding author of the new study.

The BU researchers hypothesized that this surprising increase might be due to exposure to repetitive head impacts. To explore the relationship between contact sports participation, multiple brain diseases, and symptoms characteristic of REM sleep behavior disorder, Stein and scientists at the VA Boston Healthcare System and the BU School of Medicine analyzed the brains of 247 athletes donated to the Veterans Affairs-Boston University-Concussion Legacy Foundation (VA-BU-CLF) Brain Bank.

Since CTE can be diagnosed only after death, the researchers interviewed family members of study participants to find out if they had experienced symptoms of REM sleep behavior disorder during their lives.

“It’s usually the spouse we talk to, but sometimes other close family members, asking them if [their loved one] would act out their dreams, thrashing around in bed. It’s really quite scary for people and their partners, and it can lead to some injury because they’re not able to control their movements—they can hit things around or injure their bed partner,” Stein says.

From interviewing family members, they discovered that a third of the study participants had displayed symptoms of the disorder while they were alive.

“We found that CTE participants with probable REM sleep behavior disorder symptoms had played contact sports for significantly more years than participants without these symptoms,” says study first author Jason Adams, a former research assistant at BU, who is now pursuing an MD/PhD at the University of California, San Diego. The odds of reporting symptoms, he says, “increased about 4 percent per year of play.”

“Repetitive head impacts may damage and disrupt cells in the brain’s sleep centers,” Stein says.

The study further examined the brains of those with CTE and REM sleep behavior disorder and found an unexpected association between sleep dysfunction and changes in brain tissue. Most patients with REM sleep behavior disorder have Lewy bodies, abnormal aggregations of protein that develop inside nerve cells. Lewy bodies contribute to Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementias, and some other neurodegenerative disorders.

However, most of the CTE participants with REM sleep behavior disorder did not have Lewy bodies in their brains. Instead, compared to study participants with CTE who had not experienced any sleep symptoms during life, they were four times more likely to have tau proteins within a cluster of brainstem cells involved in REM sleep.

“Contrary to our expectations, tau pathology [found in a cluster of brainstem cells] was more strongly associated with REM sleep behavior disorder than Lewy body pathology, suggesting that [buildup of tau] is more likely to lead to sleep dysfunction in CTE,” Stein says.

An abnormal buildup of tau proteins in the brain is a hallmark of CTE, and the quantity and density of tau buildup in the brain is used to characterize the severity of an individual’s disease. That system of diagnosing and characterizing CTE, known as the McKee CTE staging scheme, was developed in 2013 by a team of BU CTE researchers led by Ann McKee, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and a BU School of Medicine professor of neurology and pathology, who is also a coauthor of this new study. (Last month, another study published in Acta Neuropathologica proved that the McKee staging scheme for CTE accurately represents the progression of tau pathology in CTE and correlates with clinical dementia.)

BU CTE researchers have previously shown that the number of years of contact sport participation predicts the severity of tau buildup in the brain, as well as the stage of CTE as determined by the McKee criteria. Additionally, they have found that individuals with a history of repetitive head impacts and CTE diagnosis have accumulated a buildup of beta-amyloids—peptides that make up amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease—at an accelerated rate, and at a younger age, in their brain tissue. Those individuals also had an atypical pattern of beta-amyloid deposition within blood vessels.

“Overall, more and more studies are showing that repetitive head impacts that can occur in contact sports are associated with increased risk for multiple neurodegenerations,” Stein says.

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration; a Clinical Sciences Research and Development Merit Award; Veterans Affairs Biorepository; the Alzheimer’s Association; the National Institute of Aging; the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; the Boston University Alzheimer’s Disease Center; the Department of Defense Peer Reviewed Alzheimer’s Research Program; and the Concussion Legacy Foundation. This work was also supported by unrestricted gifts from the Andlinger Family Foundation and World Wrestling Entertainment.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.